In the fall of 2019, a tiny studio named after the constructed language of pre-revolutionary Russian poets released a communist RPG without a combat system named Disco Elysium. It will likely eclipse 2 million copies sold worldwide by this summer.

What is the secret to Disco Elysium’s wild success? The perfect answer is difficult to unearth, if even extant at all. Like the great iconoclasts that have come before it, Studio ZA/UM’s starting-gate slam dunk is a beast all its own. The dialogue may show flashes of Planescape: Torment, many character portraits wouldn’t hang too oddly in a Jenny Saville exhibit, and there’s a dead man who is basically some holy fusion of Lenin and Marx. But, there’s also a necktie that screams at you to go off the chain, a skill that allows you to understand “cop culture” when you level up, and some of the most intimate, complex, and compelling writing I’ve ever had the chance to experience in an interactive medium.

RPGFan had the chance to chat with Justin Keenan, a writer and narrative designer on Disco Elysium, just weeks after the release of The Final Cut, an expanded version of the title released on PC and PS4/5 on March 30th.

Eva Padilla: Congratulations on just releasing The Final Cut last month! In an interview with Polygon, lead writer Helen Hindpere had stated that this edition is “The Disco Elysium we dreamt of launching when we started development in 2014.” How does The Final Cut in 2021 differ from the dream of Disco Elysium in 2014? What additions specifically came from player input instead of original developer intent?

Justin Keenan: The version of Disco Elysium that we released in 2019 was very much an indie production. There were some rough edges, a few places where the execution didn’t quite match our ambition or vision. Adding full VO is the most obvious change: Not only is every line voiced, but the recording quality has increased tremendously. You really get a sense of the medley of voices that make up Martinaise now. The sound of the game now matches its visual splendor. Along with those new and improved voices, our animator, Eduardo Rubio, went all-out to make each character really live and breathe when you encounter them. The whole experience is just much richer and more luxurious than what we could achieve on release in 2019.

As for player input, one critique we really took to heart was the idea that the various ideologies the player can align with didn’t feel very narratively satisfying. Those choices felt cosmetic, in other words. The political dream quests were something we’d been discussing for a long time, but unfortunately they were one of the features that wound up on the chopping block before the original release, and we’re grateful to our players for giving us an excuse to revive them for The Final Cut.

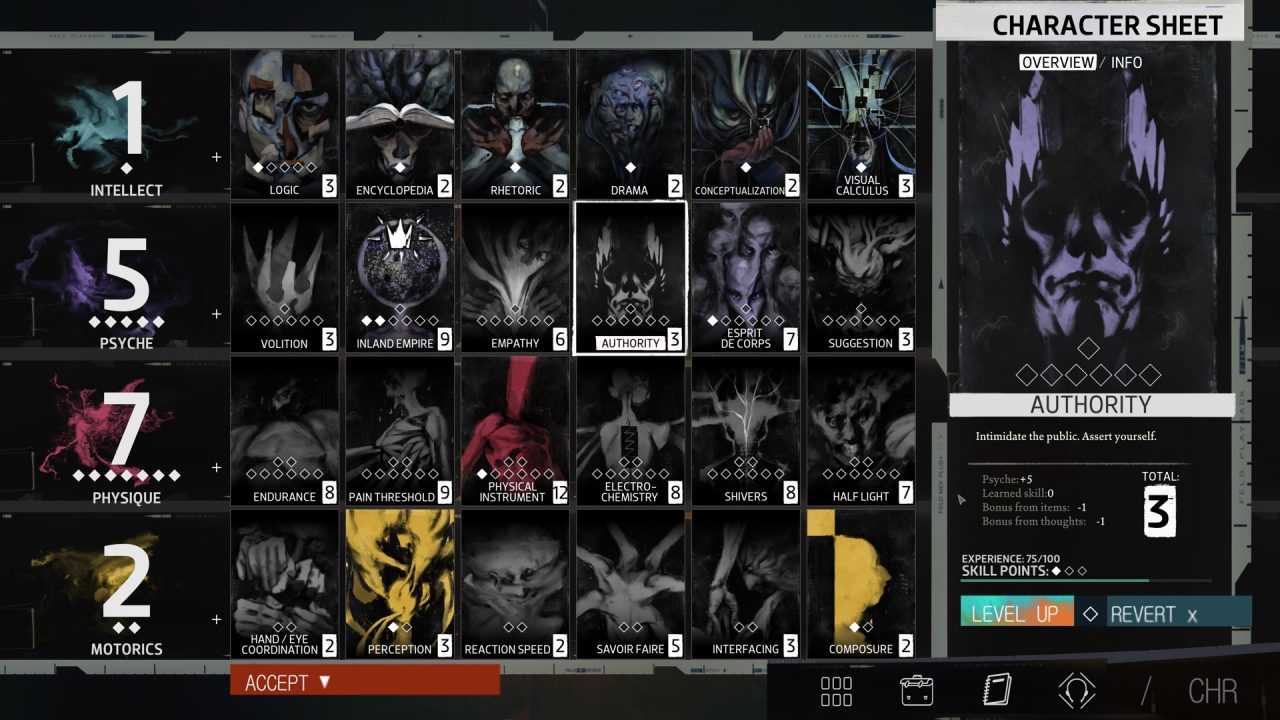

EP: One of the biggest additions to The Final Cut is Lenval Brown, who now voices all the various skills swimming around Raphaël Ambrosius Costeau’s (er, Harry’s) head. How has that changed how the development team approached the skills, and what was this undertaking like for both Lenval and the devs?

JK: There wouldn’t be a Final Cut without Lenval. His voice is just so perfect that when we write now, it’s impossible not to hear Lenval’s voice reading every piece of narration. Sometimes it’s like we’re writing the narration for Lenval specifically, the way that when we write Kim we’re always writing for Julian Champenois. His voice brings a steadiness to the game’s soundscape, even when he’s reading your most outer inner thoughts, he makes sure that you as a player feel absolutely situated in Harry’s psyche. I especially like the way Lenval’s steady, even readings change the way you might hear some of your loudest and most insistent skills — I’m thinking of Half Life, Drama, and Authority especially.

EP: Despite being a unique experience for many players, Robert had stated in a Gamespot Audio Log that the goal of the game was to be a “mass product for mass entertainment.” What parts of the game had to deviate from accessibility or entertainment as their guiding principle but are nonetheless necessary to keep Disco Elysium feeling like Disco Elysium?

JK: I would say our guiding principle was to make the kind of game that we desperately wanted to play ourselves, and we had a feeling there were a lot of other players like us out there. We had no idea there’d be more than a million of those other players, but I think that just shows that there’s a large market out there for games that are thematically rich and politically engaged. Maybe one of the reasons Disco Elysium reached the audience that it has (an audience that includes a lot of non-traditional gamers) is that the storytelling and writing are dense and rich, but the gameplay itself is pretty straightforward. By that measure, it’s one of the most accessible RPGs out there.

The other thing I want to say is that at no point in writing Disco Elysium did we ever say “we need to dumb this down to make it more accessible” for some imagined player. Our experience has been that players respond on the same level that you speak to them. It’s funny, online commenters frequently get a bad rap, but it’s genuinely restored my faith in humanity to browse our Discord or even Reddit and see so many people of wildly different backgrounds and experiences discussing the game and sharing their extremely thoughtful and passionate responses to it.

EP: Revachol is one of the most lovingly crafted environments I’ve ever had the pleasure to roam around and make bad decisions in. To what extent is Revachol’s political setting (forgotten and irrelevant communists, liberal technocrats running society at the behest of capital, fascists and traditionalists filling the gap left by the communists) a reflection of the writing team’s individual countries, and to what extent is it a reflection of the world at large?

JK: One reality of our current age is that similar conflicts seem to be playing out in wildly different countries and societies. There’s been a real reemergence of ideologies both on the left and the right that many people (especially the people who tend to run governments, corporations, and major media outlets) had long assumed were dead and buried, when in fact they’d never left. But to your question, this dissatisfaction with the liberal technocratic order seems to be a global phenomenon that manifests itself according to the material realities of individual places. Revachol, for us, is a reflection of that general truth even though its particulars are drawn from a number of disparate sources and experiences. That’s why it feels both immediately recognizable to so many people while also remaining intensely mysterious and idiosyncratic, the way all real places are.

EP: One criticism I’ve seen of the game is that some players feel they are unable to relate to Harry, whether that’s through the constraints of in-game dialogue options or occasionally due to his perceived identities/affiliations. Is Harry meant to be more of a character to be observed by the player, or a cipher for the player to live through?

JK: That’s an interesting question, and I think it reflects a broader tension between different approaches to role-playing. The reality is that the vast majority of players reflexively pick the dialogue option that the game presents as the ‘good’ choice. They’ve been conditioned to expect and pick those options by RPGs for decades. The thing is, real life isn’t usually made up of recognizably ‘good,’ ‘bad’ and ‘sarcastic’ options. It was very important to us that Harry feels like a real character, with as rich and interesting an inner life as a character in a great novel. So no, he’s not a cipher, but he’s also not an object to be coolly appraised. Our theory was that by creating a main character with a real interior life, players would actually identify with him more than the sort of infinitely tailorable but ultimately hollow avatars that they’re used to. And judging from the volume of Harry fan art that players have produced, I would say it worked.

EP: I think some players would be upset if I didn’t ask this particular question, so I must ask: Why can’t we kiss Kim?

JK: Because the thing about desire is that it’s stronger when it’s not totally satisfied.