Editor’s Note: This piece contains heavy spoilers for both NieR Gestalt and NieR: Automata.

The power of words is a common theme in art. As an English teacher, I tell my students at least once a week that although reading helps us to understand ourselves, the most important part about reading is that it helps us understand the world around us. The more we read and the more we watch, the more we understand each other. It naturally follows that the more we build this empathy, the more kind we are to others.

In that same tradition, NieR Gestalt is a game about words and their power to help us understand others. Whether this be in the first playthrough, where we have riveting text adventure sections, or in the second and third, where we grow to understand through additional cutscenes and dialogue what the Shades we have been fighting against for several hours are feeling, our understanding of the world of NieR is a constantly moving target, and we come to understand almost every character by the final moments.

In the end, though, Taro argues that words alone can’t save us. They can’t stop us from damaging the world as we chase what we think is “right,” even if they do help us understand the other side.

Throughout the course of the first playthrough, we have what almost everyone would see as a righteous mission: to save our daughter, Yonah, either from the plague which has infected her, or from her “evil” captors. The game presents us with a fairly standard set of narrative features, all the way down to the five “keys” we have to pick up to finally face off with the Shadowlord, Yonah’s captor. Taro even plays on the “Sad Dad” trope that has become even more common in the decade since NieR released. Of course, we pick up friends like Grimoire Weiss, Kainé, and Emil along the way, and despite their flaws (okay, Emil doesn’t have any) we come to love, trust, and fight for them. We come to understand them and empathize with them. After all, they ultimately fight for the same cause as you. They help you in your ultimate quest: to save Yonah.

The reason we see this path as noble, of course, is because we are trained to. We’ve played video games before. We’ve seen this narrative. The Shades are dark, amorphous creatures. We can’t understand them when they talk. They don’t look like us, and they certainly don’t sound like us. When we first encounter the Shadowlord, we can’t understand him, and all we know about him is that he is taking our daughter. And so, of course, we continue our quest, killing everything in our path.

When we finally arrive at the Shadowlord’s castle at the end of the first playthrough, the answers to the mysteries surrounding the Shades are finally revealed. They are the true humans. You are simply a shell, waiting to be filled with the Shades when the pandemic threatening to wipe out humanity has passed. It turns out your friends Devola and Popola have been secretly working to this end. But at that point, it’s too late. You’re too invested in this tried-and-true quest. As Devola and Popola put it, “You have your own motives, your own desires. And we have ours. I fear it really is just that simple.” The new knowledge you gain about your foe does nothing to deter you.

In the final moments, Nier acknowledges the Shadowlord’s humanity, and even the importance of his cause, but he doesn’t care, shouting “You want me to understand your sadness? You think I’m going to sympathize with you?” He continues forward in his quest, violence and all, ultimately cutting down the Shadowlord. Again, even with the new understanding Nier gains, he doesn’t change. Devola and Popola’s words don’t matter. His goals are his own, and he will destroy anything and anyone to save what he loves, even when he knows the other side is fighting for the same cause.

Even when we do understand our enemy by the end of that first playthrough — when we get that empathy — we continue to engage in violence against the “other” again and again in subsequent playthroughs. The game even forces us to do this to get the true ending. Nevertheless, we persist in each playthrough, cutting down the “true” humans in an effort to save the person we love. Each area we explore again gives us moments behind the curtain. Now we can understand their words. The boss at the top of The Lost Shrine is kind to younger shades. I still killed him. The robot at the junk heap didn’t kill anyone. His name is Beepy, and he is incredibly cute and lovable, but still, I killed him. Again and again. The same goes for the leader of the wolves and every other shade that got in my way. I killed them all, regardless of the emotional cost. Nier, and the player by extension, are not alone in this, either. The Shades, the King of Facade, Kainé, even Emil, continue to destroy others for the sake of their own “righteous” causes.

Finally, after repeatedly visiting destruction on everything in your way, at the end of the final playthrough, you’re given a choice to sacrifice yourself to save Kainé. This means losing your save data and everything you’ve worked for. Much has been made of this “true” ending, but ultimately, it does nothing to end the cycle of violence. Certainly, the emotional impact of actually sacrificing yourself, your save data, and all your hard work is strong. But at the end of the day, you’re still sacrificing yourself for your own cause: your friend Kainé. While this is noble, it doesn’t address the core problem of misunderstanding and violence. It will continue, and it will lead to everyone’s destruction, Replicant and Gestalt alike. The question of how to resist this cycle, of how to change anything, is left open, with none of the endings resolving the conflict. As Popola puts it when she lashes out in revenge against you, “It’s way too late to stop. No one stops.”

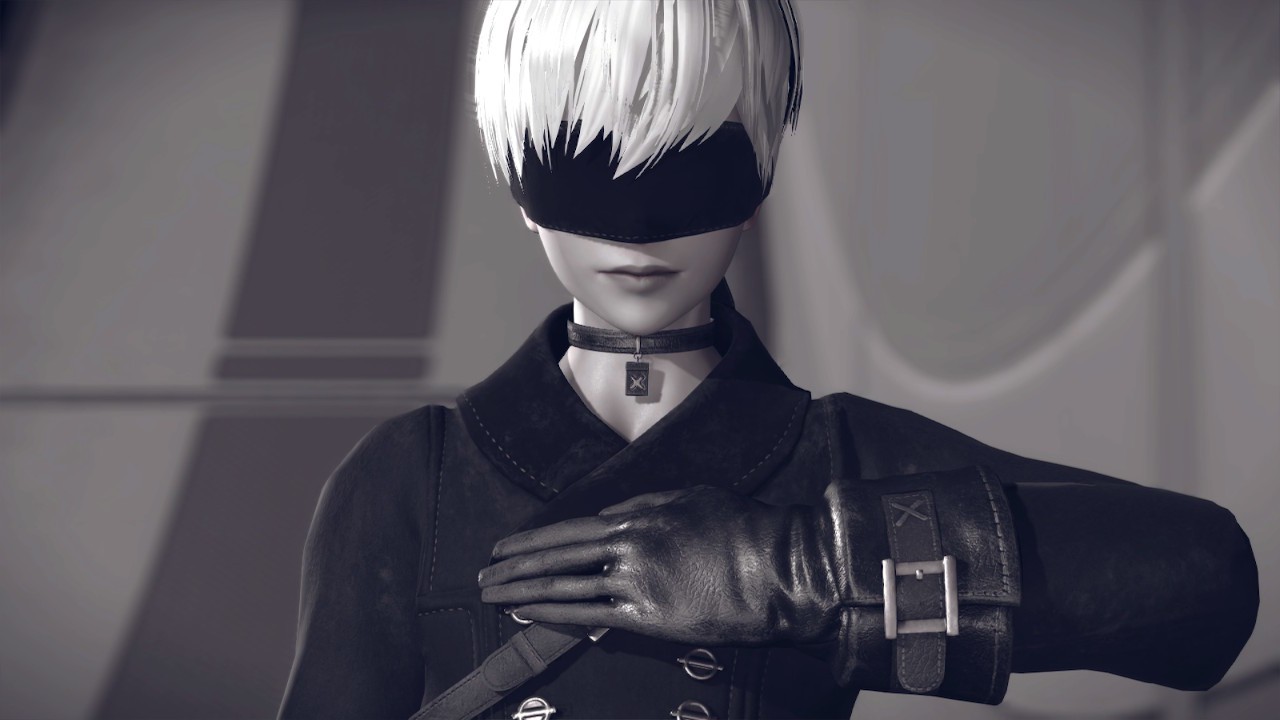

That is, until NieR: Automata. Here we are presented with a world, almost 10,000 years later, that has remarkably similar conflicts, but this time it’s between androids and machines. Both sides have their righteous causes. Whether it be revenge for characters like A2 or 9S, philosophy in other cases, or even religion, they’re all searching for something — something to protect and something to believe in. And, just like Nier in the first game, they’re willing to fight for it once they find it.

But that’s the problem. Because they’re all willing to fight for what they believe in, they perpetuate the same cycles of violence as in NieR Gestalt, the same anger, and eventually, even the same “understanding” of the other side’s motivations, both of which are predicated on a fabrication. But again, even with this new understanding, they continue to push forward and fight for their respective causes, which leads to the death of everyone on both sides. The cycle still hasn’t stopped.

So, until the very final moments, it seems like Automata is heading in the same direction as Gestalt. And, once again, at the end, the game asks you to sacrifice your save data and all your hard work. But there is a key difference: this time you’re asked to do it for someone you don’t even know. Are you willing to sacrifice yourself for a stranger? Someone you might not even like? You even get to see the true ending without wiping everything out this time, so the motivations present in Gestalt are gone. But, even if it took a few playthroughs, I eventually agreed to it. It was the right thing. The implication is clear: we don’t need to have the “words” of others to understand their pain; the human struggle is universal. This is reflected in both the encouraging messages you write to others at the end, many of which are written in languages that are not English, and the final mix of “Weight of the World” that plays over the credits, blending a variety of languages, and even musical styles. We don’t understand all the messages and all the lyrics, but we don’t need to: we know they’re in this struggle with us. Taro insists that we don’t need to understand someone else to help them; we should decide that every human is worthy of empathy, worthy of love, and ultimately, worthy of sacrifice.

We are so often told that in order to get by in life, we have to “believe in something.” Dedicate ourselves to a cause, and we’ll find a meaning and a purpose in this life. Taro rejects that. Every character who fights for a higher “purpose,” whether it’s their daughter, their friend, a religion or a philosophy, finds themselves in despair, often leaving destruction and death in their wake. Rather, Taro argues for something at once loftier and much simpler: fight for everyone. Don’t make words, or even empathy, the bar for helping other people; it’s not enough. We don’t have to understand others to value them. Value them because they’re human, and because they struggle just like the rest of us. No amount of understanding should matter. If we can do that, then maybe we can stop perpetuating the constant cycle of conflict we keep coming back to.