With the NieR: Automata Ver1.1a anime finally up on its feet (despite the premature hiatus), it seems like an opportune time to reflect on what made the game it’s adapting so special. With the show sticking closely to the game’s story so far, I want to talk about some aspects of the source text that can’t be adapted. NieR: Automata is, after all, a remarkable storytelling achievement for the ways it expresses philosophical themes while playing into and subverting the language of games. This is what narrative design is about. The way the game plays with its mechanics, systems, sound, UI, genre conventions, etc., all contribute as much to the experience as do the plot, characters, and writing.

SPOILER ALERT: This article is an exploration of some of Nier: Automata’s themes and possible meanings based on specific moments and design decisions. To make such an analysis interesting I have to spoil some things! So if you haven’t played the game and still intend to (you should!), you’ve been warned.

NieR: Automata is a game that explores the idea of being human. Ironically, it does this without featuring a single human character. The characters are all (as the title suggests) automata that fall in one of two camps in the midst of a centuries-spanning war with each other: there are the androids, our protagonists, created in humanity’s image to take back Earth from alien invaders; and the machines, who served the alien army that overtook Earth millennia ago. We learn that these automata’s organic creators have gone extinct, leaving them to unknowingly continue a war that has lost its original purpose.

Meaningful Violence

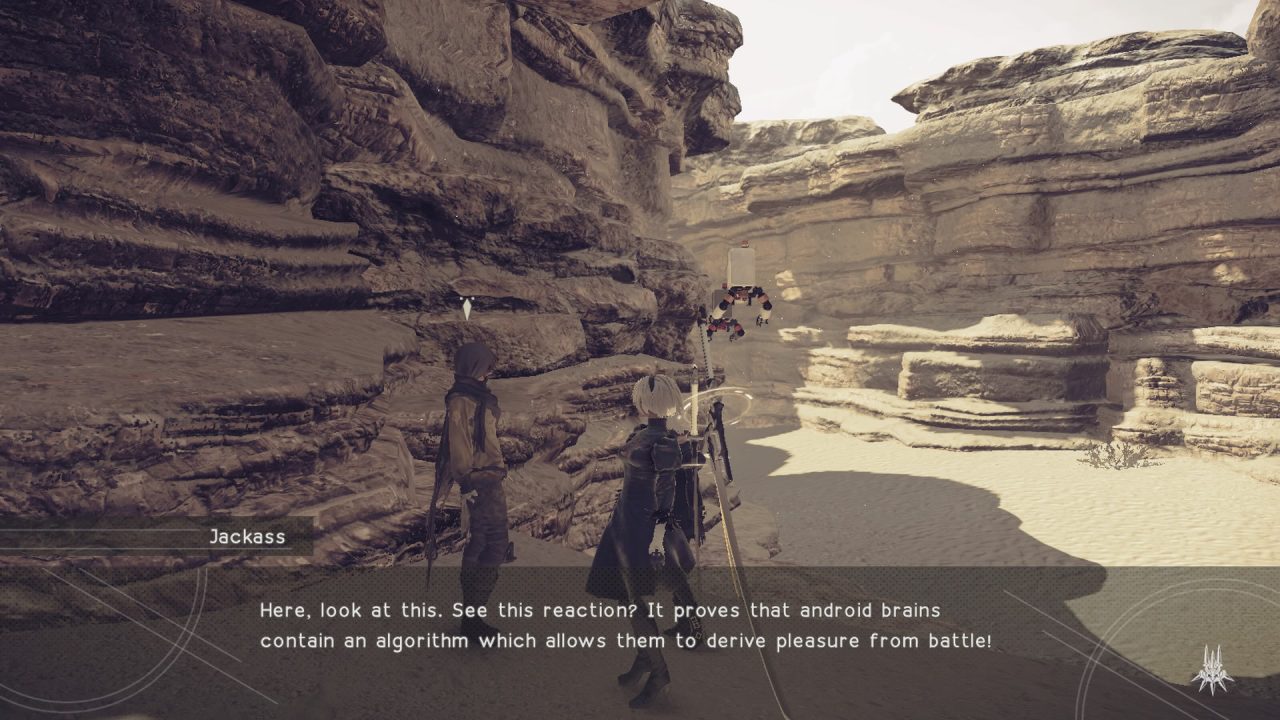

Automata most often plays like a standard action RPG. The player receives tasks, and must traverse space, interact with NPCs, and defeat a ludicrous number of enemies to fulfill these quest obligations. The game’s prologue immediately throws us into a cinematic action sequence that has us decimate numerous machine lifeforms, who we are led to understand as the natural enemies of our android characters’ cause. As one might expect in an action game, the solution to the conflict is to kill the machines. However, the more we fight these machines, the more the game starts to play with this generic convention. In the middle of fights, machines begin to express human desires through their own comically (and, as a result, morbidly) automated voices: They express the desire to avenge their fallen comrades, they plead for their lives, they beg for the fighting to stop. Our android protagonists frequently dismiss these expressions because they think themselves superior to the machines by virtue of being created in the image of humankind. They respond with quips such as: “Don’t listen to them. They don’t actually know what they’re saying. Machines don’t have feelings.”

However, as the player helping the androids commit these genocidal actions, I couldn’t help but be disturbed by these phrases. What if the machines can feel? Should I be doing this? Sometimes I would abandon a fight mid-action after hearing these uncanny utterances from my enemies. Some machines, like those in the carnival, are downright passive despite being targetable and killable like any other. Few games so effectively make the player question what they’re doing, and, in turn, question the conventions that it is based in. If all videogame baddies expressed human emotions and desires while we wail on them, representing violence suddenly becomes much more complex.

The success of the game’s impact on the player depends on their emotional investment in the characters. The androids are likable because they work towards a shared purpose and are willing to sacrifice themselves to protect each other and their cause. Despite being told that “emotions are forbidden” for them, they appear and behave quite humanly — eventually coming to express love, hatred, compassion, misery, and other powerful feelings that emerge from their harrowing lives. But the quintessential difference between us and them is that they were handed a clear purpose for their existence: to fight against the enemy in the name of humanity.

This drive is expressed in the quests they receive, which function as necessary goals the androids unflinchingly agree to and internalize. Playing as 2B and 9S involves the characters accepting the tasks handed to them, clinically executing them, and engaging in occasional reflective banter about the meaning of these actions. Only when we first play as the rebellious A2 do we receive a quest, not in the form of an assignment from headquarters or other NPCs, but a personal goal the character has decided for herself.

The game’s greatest irony, however—which is crucial to its functioning as the game it is—is that the means to the androids achieving a shared purpose is perpetuated violence. Love, hatred, and the sense of obligation that power these emotions inform our characters’ motivations in the latter portion of the game. Yet, in existing solely to prolong an eternal war against a villainized ‘other,’ violence becomes their only outlet. In this sense, the game does a great job contextualizing the violence inherent in its genre so that it almost always feels worthy of questioning and becomes meaningful in that way.

Bodies of Data

Automata wears its interest in exploring philosophical and theological themes loudly on its sleeve. One of the game’s primary philosophical concerns is asking what constitutes the self or the true essence of a person. The androids have reproducible bodies, but their data is depicted as more individual and essential. The game represents the player ‘dying’ as the destruction of the current player-character’s body. The android’s data—which is, importantly, also the player’s data—is then uploaded to one of the game’s save points, where a new body gets deployed so we continue our journey with our character’s consciousness fully intact. The player can then return to the spot where they ‘died’ and retrieve the plug-in chip upgrades that were equipped on the old body. The game makes a point of this by featuring an unavoidable death at the end of its prologue section. It wants the player to understand that destruction of the androids’ bodies doesn’t necessarily equate to their death. After all, this narrative detail goes against standard videogame logic that a gameplay death is the same as the player-character’s death. This usually makes tackling death a tricky subject in videogames, but playing as an android bypasses the issue because their nature is closer to that of videogame avatars themselves. They are technically immortal beings that can be infinitely reborn.

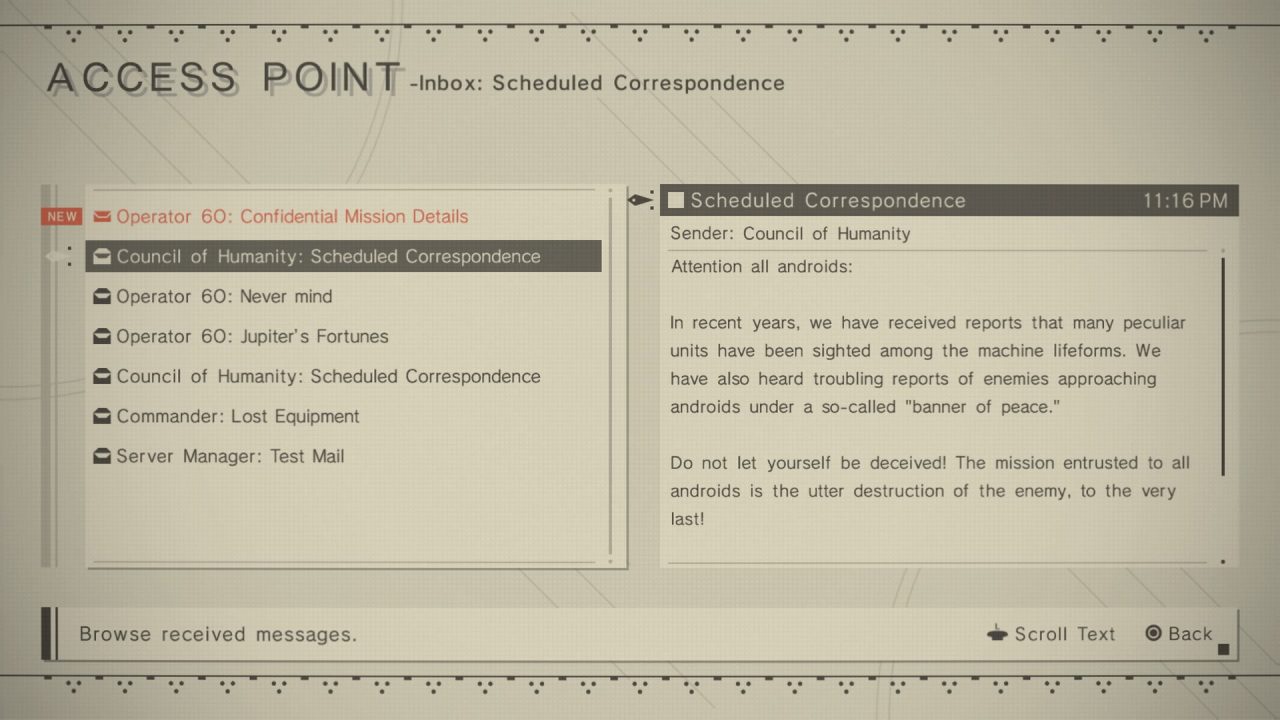

The game frequently reminds us that we’re playing as androids right down to its UI. Loading screens appear as a bootup sequence; plug-in chip customization involves literally installing new parts into the androids’ bodies; and world-building intel, spatial mapping, and the androids’ internal database processes quest details. Moreover, the game’s HUD elements must be equipped with the appropriate chips—integrating the arbitrary ways that videogames represent character ‘health’ and include QOL features like mini-maps with the nature of the protagonists. This logical way in which the UI functions and displays shows how all videogame UI is android-like. In other games, we are in effect always playing as androids despite being told by the game’s story that our player character is made of flesh and bones. Automata revels in this cyborg logic that videogames work from and usually take for granted. It wants us to feel the humanity of its characters just as it insists on reminding us that they’re not human.

The game’s NPCs often speculate about their humanity (or lack thereof). The side quests they offer are usually fetch quests through which their existential concerns unfurl. The first side quests come from the Resistance Camp’s shopkeepers and are mandatory, functioning as a sort of tutorial for the system. The Resistance Camp’s Supply Trader, for instance, refuses to replace one of his legs due to a lingering feeling of existential dread. He’s already substituted all his other body parts at least once and wonders if getting rid of this final piece of his original body would make him lose a fundamental part of himself. A similar situation unravels with the Weapons Trader. Upon completing his side quest, he questions whether the weapons he creates and sells only result in more of his friends’ deaths. Despite their generic naming conventions, Automata’s shopkeepers point players to think about what implications their inventories—which encompass the core systems of the game as an action RPG—have on how we interact with the game world. Chips alter the androids’ being, while weapons destroy other beings.

Even though the androids understand how their bodies are replaceable and their data exists apart from it, they can’t help but compare their existence to their human predecessors. With regards to the explicit Christian symbolism the game draws on, an android’s data is akin to a human soul. Working from the belief that the soul transcends the body and encompasses the ‘true self,’ Automata plays with the notion of death between the destruction of an android’s body and the erasure of its data.

What’s in a Save File?

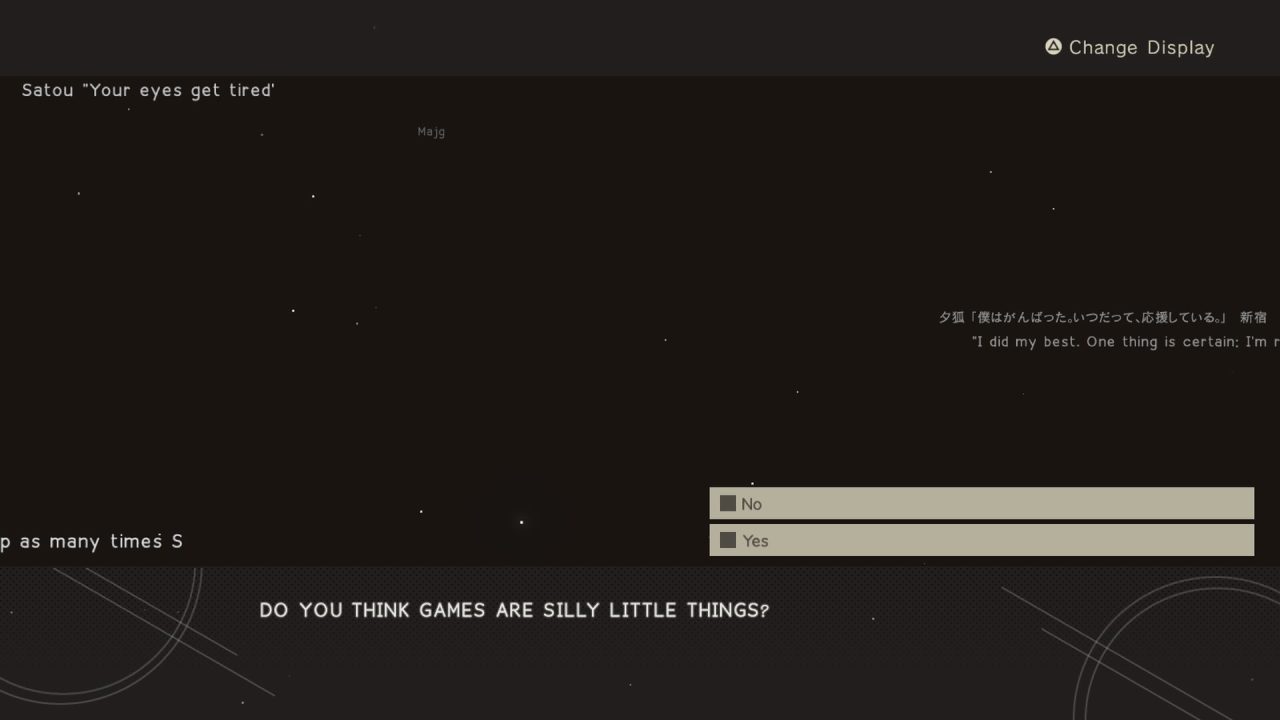

Let’s talk about the game’s Ending E, its final canonical ending, which gives the player a purpose external to the game world that nevertheless reflects the main themes of its central narrative. Obtaining this ending requires us to battle against the game’s credits to defy the protagonists’ tragic fate, reconstructing them so that they might have a chance at a real life (although whether this will be successful remains ambiguous). The battle against the credits escalates to a brutally challenging affair. Unless the player is remarkably skilled, they will need to accept aid from a fellow player through the game’s network features to complete it. This aid is not in real-time, but during the battle the game’s interface displays that the other player’s data is destroyed as they protect us. Ensuring this sacrifice is not made in vain fuels the player as they complete this strange and metatextual ‘final boss.’

After completing the sequence and viewing the game’s final cutscene, the player is asked if they would like to sacrifice their own save data to help another player, a stranger, reach this ending. It’s a rather jarring choice. A save file is a piece of data that contains a trace of the player’s experience. It is tied to the memory of that experience, and functions as an archive of items and lore-filled intel that the player dedicated time and effort to accumulating. Moreover, if the player had more content they wished to complete, the save file could still be a site for future experiences. Other than perhaps a physical copy of the game itself, the save file is the most material connection between a player and their gameplay experience. Through this act of real sacrifice, the player can help another player to witness the only hopeful ending of the game. It’s an ingenious way of connecting players of a single-player game in a manner that penetrates reality and encourages empathy.

The choice remains powerful for how it prompts self-reflection. When a game allows only diegetic agency for the player, it is easy to immerse oneself in the virtual world without reflecting meaningfully on the experience. Yet, when the player is made to recognize that a choice they can make in-game will affect another player’s experience as well as their own, suddenly they are confronted with a dilemma. What’s important here isn’t that every player chooses self-sacrifice and somehow becomes more human by doing so; but that, regardless of what the player chooses, they will have conflicting feelings about their choice.

Many RPGs prompt players to make complex moral choices in simulated scenarios. Yet this choice, due to its grounding in interpersonal reality, felt more meaningful than any other. Either the player must deal with the effects an actual loss (by sacrificing their file) or acting selfishly (by preserving something important to them). Both scenarios involve an emotional response that is quintessentially human, even if the former is arguably the more transcendent of the two in the way it supports the game’s narrative themes investigating what constitutes being human.

Playing Androids

Within the game, this willingness to sacrifice is shown repeatedly in the selfless and caring actions of the androids. They fight for humanity and engage in a constant cycle of destruction (both of their bodies and memories) because they were designed to and have internalized this purpose. We control the androids through these obligations, which take the form of traditional RPG quests where there is little room for deviation via player agency. But once the androids realize the extinction of humans and, consequently, the meaninglessness of their existence, it provokes a nihilism that is foundational for their ascension to humanity.

The game’s androids are clearly capable of human emotion and cognition, but they differ most significantly from their creators in the need to serve a pre-determined obligation. They behave like androids partially because we, the human players, play them as androids. In this sense, the android can be seen as the representative figure of a videogame’s player-character— a being whose freedom is relegated to the confines of game design and the player’s whims. Automata’s Ending E only becomes available once the characters reach an existential rock bottom. Through it, we can set these characters free so that they may begin to create their own meaning.