“…you must remember that the political development of the masses proceeds not in a direct line, but in a complicated curve. And is not this, after all, the essential movement of every material process?” ~ Leon Trotsky, History of the Russian Revolution

The rag-tag revolution opposing the monolithic tyrant is a classic and favorite story device. Rightfully so, as the vast majority of people will themselves never be integrated into the power structures that so often inconvenience and oppress them. Revolution is one of the tools that has shaped the world throughout time, and therefore is ingrained in many cultures and histories. Naturally then, one’s involvement in a righteous revolt is a powerful fantasy, and video games are especially eager to present this instantly-relatable narrative. Unfortunately, these tales are often hemmed in by the directness of their narrative lines, the very directness that Trotsky insists is the antithesis of material process. Indeed, many video games are simply not equipped to expound on the science and theory of uprising beyond the most surface-level themes.

This does not devalue the theme or the media that utilizes it. Revolt theory, like many tumultuous topics, is endlessly complicated and the number of factors that can shift a situation is unmanageable. Realistically simulating this phenomenon would be an unreasonably heavy task in most cases, so the responsibility usually falls on the writers of the game’s story. In the case of JRPGs, generally the existential is of more interest to writers and audiences, so even though many do center on a popular uprising initially, as is the case in Final Fantasy VI, Bahamut Lagoon, and many others, there almost always is a point where the concerns of political power and the suffering of the oppressed utterly fall away to supernatural matters.

If one were looking for real-world lessons in the messages of these games, there is still plenty to chew on. In many cases, the supernatural forces that obliterate comparatively mundane concerns of everyday people are unleashed or otherwise enabled by those in power. This is a handy metaphor for weapons of mass destruction, for example.

Thus, in these games the revolution is a launchpad to establish a journey to the epic and otherworldly climaxes of these works. It is a common and classic trope, but in the right hands it can be very satisfying.

Reign It In

Ogre Battle 64: Person of Lordly Caliber is an unusual game in many ways, not the least of which is subverting these story expectations while letting the player marinate in the suffering of the lower and working-class of Palatinus for practically the entire story — despite the acknowledgement of the supernatural. The point of the story is the plight of the people. The demons unleashed upon the land play a significant role in the details and provide texture, but Ogre Battle 64 never centers around demonic forces threatening the world. It makes sure from the beginning that the player understands it is a game about class warfare and the intricacies of unrest.

Palatinus, a puppet-state of the mighty Holy Lodis Empire, is a nation that comes across as inert and weak. It seems its purpose is to force its laborers to mine essential minerals for Lodis. Its nobles and rulers get fat while they do nothing to advance the well-being of the population. It’s a familiar story indeed.

Magnus, the protagonist, is a noble with personal ties to the royal family of Palatinus. In fact, Prince Yumil, the heir to the throne, is Magnus’ childhood best friend. Yumil is insufferably ignorant, as one might expect a royal child to be, so when Magnus decides to leave for the officer’s academy, Yumil complains an awful lot about it.

“Kings are the slaves of history.” ~ Tolstoy…

Yumil is almost a bishounen character, but unlike many others, he’s presented as a crybaby and ignoramus not meant to garner any sympathy. His role in the plot is revealed very soon to be from the Tsar Nicholas II template. A largely unassuming person who’s unfortunately expected to rule, and whose lack of imagination and empathy toward people results in harsh violence perpetrated upon them.

“What is going to happen to me and all of Russia? I am not prepared to be a Tsar. I never wanted to become one. I know nothing of the business of ruling.” ~ Tsar Nicholas II

Yumil’s sensitive and kind nature causes him guilt. He sees all the ills of his world as the result of his own “weakness,” as if a sensitive nature and compassion were signs of weakness. He overcorrects and seeks power. This is a useful glimpse into his worldview, one which is at odds with his nature and therefore causes him to abandon said nature in service of his worldview.

Access to… education and the resultant status is itself a privilege that the people who are expected to carry out the revolution do not have. Fights for equal rights are often thus stratified in a way that may continue to inflict harm on people in the less-advantaged sectors.

Let it be clearly stated: Both the fictional Yumil and the historical Tsar Nicholas II are not merely passive bystanders to violence, but are responsible for directly inflicting it on their populations. Many have observed, however, that this is a result of their upbringing and the expectations thrust upon them, and under different circumstances they would likely not be the kind of people who would harm others. Those same folks might say that King Louis XVI of France was similarly inoffensive, not the type to desire that others be persecuted, but not the type to upend the paradigm in order to correct injustice either.

“I die innocent of all the crimes laid to my charge; I pardon those who have occasioned my death; and I pray to God that the blood you are going to shed may never be visited on France.” ~ King Louis XVI of France

Privilege Given, Privilege Taken

As expected, Magnus turns coat and joins the Revolutionary Army. Frederick, the leader of the Revolutionary Army, is a classic Robespierre or Soviet revolutionary intelligentsia figure. Intellectual, educated, and idealistic. Throughout history these attributes have proven to be potent components of revolutionary leadership, however access to this type of education and the resultant status is itself a privilege that the people who are expected to carry out the revolution do not have. Fights for equal rights are often thus stratified in a way that may continue to inflict harm on people in the less-advantaged sectors. Certainly many of the notable revolutions in history, such as those of Latin America and the United States, have been carried out by members of the elite who were themselves integrated into the previous power structures. Their grievances were those of powerful men with very little regard for the rights of others.

Aside from those revolutions carried out by powerful men, some very important workers’ revolts in, for example, Russia and China took place. However, even Mao, Lenin and most other leaders of these endeavors emerged from wealthy or middle class families with access to education on a university level, while their constituents and foot soldiers were most commonly workers with far less opportunity.

An exception that proves the rule is the absolute miracle that was the Hatian Revolution. It’s considered the only successful slave revolt in history, and it’s declaration of independence is a singularly challenging and stirring must-read.

“… Victims of our [own] credulity and indulgence… defeated not by French armies, but by the pathetic eloquence of their agents’ proclamations; when will we tire of breathing the air that they breathe? What do we have in common with this nation of executioners? …they are not our brothers, [and] they never will be, [and] if they find refuge among us, they will plot again to trouble and divide us.

“Native citizens, men, women, girls, and children, let your gaze extend on all parts of this island: look there for your spouses, your husbands, your brothers, your sisters. Indeed! Look there for your children, your suckling infants, what have they become?… I shudder to say it … the prey of these vultures.” ~ Jean-Jacques Dessalines, Emperor of Haiti, Hatian Declaration of Independence

The example of Haiti is useful to provide a stark contrast to what is usually the case when an empire loses a proverbial limb or a government is severely challenged by those it governs. The Hatians with the least amount of power risked everything to bravely rise and take it for themselves. Ogre Battle 64 does not choose to tell a similar narrative, but rather a more historically common one. Many of the rebel leaders, including Frederick, have some influence and power in the current regime.

Thus Frederick, for all his qualities, demonstrates occasional slips in awareness of the needs of the people who look to him for liberation. This may be due to the inherent distance inflicted by the burdens of leadership or scholarship, but it also appears to be little more than an imperfect person doing the best they can. However, that overstated concept remains significant: privilege. Ultimately, this privilege must be given up to one degree or another if the cause truly wants power in the hands of everyday folks. Obviously, this kind of status or power is not easily abnegated, particularly when one deems themselves more entitled because they used their resources or power to help an altruistic cause. It remains to be seen if Frederick will fall into this trap at the story’s conclusion.

To his credit, Frederick eagerly accepts Magnus into his ranks, although he does so in a way that is initially concerning. He appears to want to pat the back of this aristocrat young man whose personal awakening apparently was enough to move him to abolish the very class system that gave him all of his opportunities. The typical questions come to mind: Why is Magnus a useful ally to the people? His experience as an officer and a soldier is very limited, having only just graduated from the academy and completed a few sorties afterward. Can’t the liberators be someone from among the oppressed classes? Who of the liberating agents in this story are from this persecuted group? To what extent does Magnus take power away from those who he wishes to empower? Thankfully, if unexpectedly, the game actually works toward satisfactorily answering these questions.

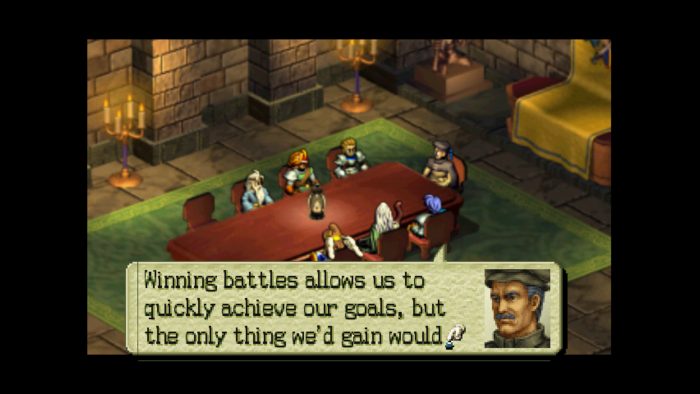

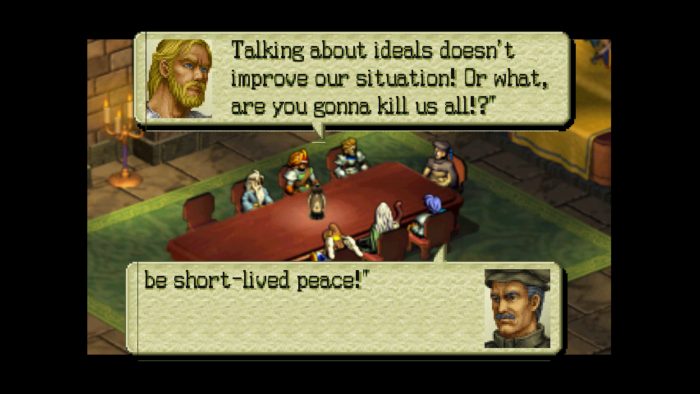

It turns out, Magnus is not the white savior, though he may be a part of the white savior machine. However, it is encouraging that he finds himself challenged by the more experienced leaders in the Revolutionary Army. Notably, after the gruff Xevec suggests liberating the Bolmaukans, an enslaved ethnic group, in hopes they would unite their forces to the revolution, Magnus zealously challenges his motives. He asks if Xevec means to use the Bolmaukans to further their aims rather than thinking of their well-being first. This question comes from a good place, certainly, but Xevec angrily shuts Magnus down in front of everybody at the meeting. It’s a splash-of-cold-water moment that makes him discover what isn’t his role in this endeavor.

Xevec insists he means to work side by side with the Bolmaukans, where Magnus interpreted his plan as using them as a tool. Witnessing an ostensibly good-intentioned yet battle-hardened man utterly humiliate the protagonist of the game is a rare and delicious experience. Xevec’s argument is solid. He reminds the leadership that eventually the revolution will have to deal with the might of the Holy Lodis Empire. Palatinus’ mining operations (carried out by an abused working class, including Bolmaukan slaves) are far too valuable for Lodis to let the miners and others of the lower classes acquire human rights. They will absolutely respond if the king is unable to put the revolution down. The freed Bolmaukans would hopefully be eager to join forces and fight their former oppressors, and it’s all for the cause.

Frederick is not a fighter, so he is a little put off by Xevec’s enthusiasm for battle (also a valid feeling). The next scene features Xevec and Frederick in private. Xevec pleads with Frederick to be realistic in his expectations. Battle is unavoidable at this point. The civil war has already started, and if Frederick hesitates, that could cost them the war and lead to a massacre. Xevec is an experienced and necessary leader who knows battle, but also knows the reason why he wages battle.

Unfortunately, Xevec is a missed opportunity as a character. He could have been a battle-hardened yet good man who disagrees with Frederick but still shares mutual respect with him. At first, his impassioned dialogue truly gives the impression he cares for the cause very much, but eventually he becomes an unfortunate cliché as he betrays the revolution and joins Lodis. Xevec could have had pure intentions. This subversion would have made Magnus, the “woke” noble, a better character. Instead he’s predictably justified in jumping to conclusions about Xevec’s intent.

A Fractured Rebellion

What the scenes involving Xevec do reveal though, is critical. First, the good guys are not all willing to bow down to the newcomer noble officer boy who just joined their side. That noble boy still has a lot to learn, and the lessons are usually tough. Second, they reveal that, as in all revolutions throughout history, this one has deep divisions. Differing opinions abound, and the next mission even has you fighting against a rival group claiming to be the Revolutionary Army. They are in fact a group that broke off because they were so frustrated about Frederick’s perceived inaction. They are depicted as bloodthirsty, but even so their frustration and motives manage to shine through. Xevec’s scenes, along with the sortie against the dissident revolutionaries, points to an important truth about political unrest: uniting a viable revolt under the same flag is not just difficult, but tragically fraught. This depiction is still very simplistic when compared to real-world history, but one will certainly find themselves surprised that the game touches on these matters at all.

There is one other unfortunate thing these scenes reveal, and that is the fact that (as previously stated) this revolution might be a white savior machine. The Bolmaukans have the unfortunate distinction of needing the revolution’s rescue. It’s not all bad, as the Bolmaukans, upon liberation, demonstrate strong agency in their own right, promising to fight for the revolution, but not guaranteeing they will follow orders. In a narrative win, the Revolutionary Army is forced to accept their autonomy. Thus we see yet more complexity in the factional makeup of this civil war.

The affair with the Bolmaukans also reveals what kind of rebellion story this is. It is not a story that takes inspiration from the Hatian Revolution, but a slightly more mundane one in which the main actors, especially the protagonist, are people with abundant political and economic resources.

Progress Meets Resistance

Ogre Battle 64 benefits from its grounded approach and surprising nuance, but it still indulges in the supernatural. Early on, Magnus’ former commanding officer, General Godeslas, is revealed to have been convinced by a superior to sacrifice his family and others to unleash the creatures of the underworld in a last-ditch effort to blunt the Revolutionary Army’s momentum. It’s dark, desperate stuff, and proves unsuccessful. The man is somewhat humanized when this same superior visits him later, rebuking him for failing, even with the help of the demons. General Godeslas is overcome by crushing humiliation and regret before being executed in his own office.

This plays into the critique leveled at many JRPGs that the existential threat overshadows the more relatable initial conflict. These elements are utilized here in a much more controlled manner that more closely reflects dirty tactics seen in history. It’s less an analogy for a nuclear bomb and more one for chemical warfare during World War 1. Much like that deadly gas, which, in addition to being horrific if used on the enemy, would kill friendly soldiers with a simple shift of the wind, Godeslas’ troops are unable to control these monsters. Many lose their lives when they turn on the soldiers instead of the revolutionaries, and now there is this genie that cannot be put back in the bottle. The underworld is now open, and the creeping threat of the monsters continues to grow.

Even with this revelation, Ogre Battle 64 never abandons its initial mission: tell a story about class conflict and oppression. This is further illustrated by Magnus’ conflict with his father, a high-ranking officer named Ankiseth.

Brother Against Brother, Father Against Son

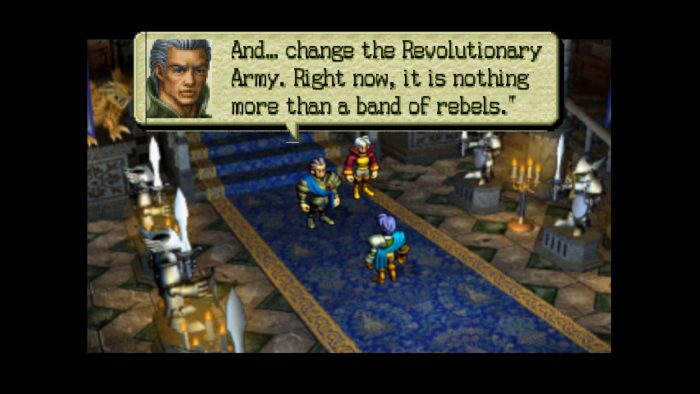

Ankiseth is naturally dismissive of the Revolutionary Army’s motives, but eventually concedes defeat. However, his lack of respect for the Revolutionary Army remains such that he insists Magnus should take Prince Yumil to the Revolutionary Army because his royal blood will be useful. As it stood, according to Ankiseth, the Revolutionary Army is just a band of rebels that needs a royal person to lead it. He says the conflict isn’t between upper and lower class, but it’s between right and wrong, saying that Magnus needs to “grow up” and “change the Revolutionary Army… now”. It’s all shockingly patronizing.

Ankiseth immediately gets stabbed by Baldwin, another high ranking officer, who then spirits Yumil away (Note: there are a set of conditions that, if met, will allow you to recruit Ankiseth to your party. I did not meet these qualifications and quite liked how the story played out because of it).

Additionally, this moment exemplifies the fact that Yumil is seen as a pawn, and potentially amplifies his desire for power, to take the reigns of history himself instead of being thrust about by the clandestine machinations of political power. I was very concerned that the game would make me side with Prince Yumil at this point. I truly hoped that Ankiseth would be proven to be blinded by state propaganda and military culture. If the game’s message had proved him to be right, and that the class system should remain and that royalty should be preserved, it would have been a betrayal of the game’s whole thesis.

Thankfully it isn’t. Prince Yumil develops into the monster he always would become, and falls to the Revolutionary Army, which would move on to destroy the obligatory supernatural forces that were behind the corruption all along. Ankiseth’s speech could have been a narrative turning point. It would have been easy to say that his experience and intelligence moved Magnus to “mature” and settle into the status quo, but it didn’t. Magnus and his colleagues understand his father to be wrong, even as Magnus mourns his death.

In reality the revolutionary movements of history have demonstrated the unfortunate necessity of harsh and difficult actions — namely, leaving behind, harming, or even destroying friends and family who would fight, literally or figuratively, directly or indirectly, for that status quo which violently oppresses so many. The notion that gentle reform is the way to free underprivileged people from institutionalized and cultural violence is a luxury apparently only afforded by fiction. Ogre Battle 64 manages to present this plight in a more realistic and respectful light than many games that share its overall themes.

The game’s subtitle is fascinating in light of its plot. What is A Person of Lordly Caliber? This subtitle looks like a feint, as if telegraphing that Magnus is the person of Lordly Caliber who should lead instead of the current power machine. Many of the game’s endings do feature a coronation (though not necessarily Magnus’) which may seem a slight betrayal of the message, yet, at nearly every turn, the notion of any such machine is challenged. What is a person of Lordly Caliber? “Who cares?” The game seems to state. “We don’t want anyone who may declare themselves thus to be in charge of anything”. It is a sentiment that rarely gets any room to breathe in the JRPG realm, and proves to be a timeless, important, and empowering message.