Matt Wardell

For years, the Schwarzenegger-esque barbarian on the North American SNES boxart of Breath of Fire II called out to me, begging me to dive into Capcom’s once-illustrious JRPG series. I answered that call, and as it turns out, that roided warrior is but a sixteen-year-old boy, searching for his papa and little sister.

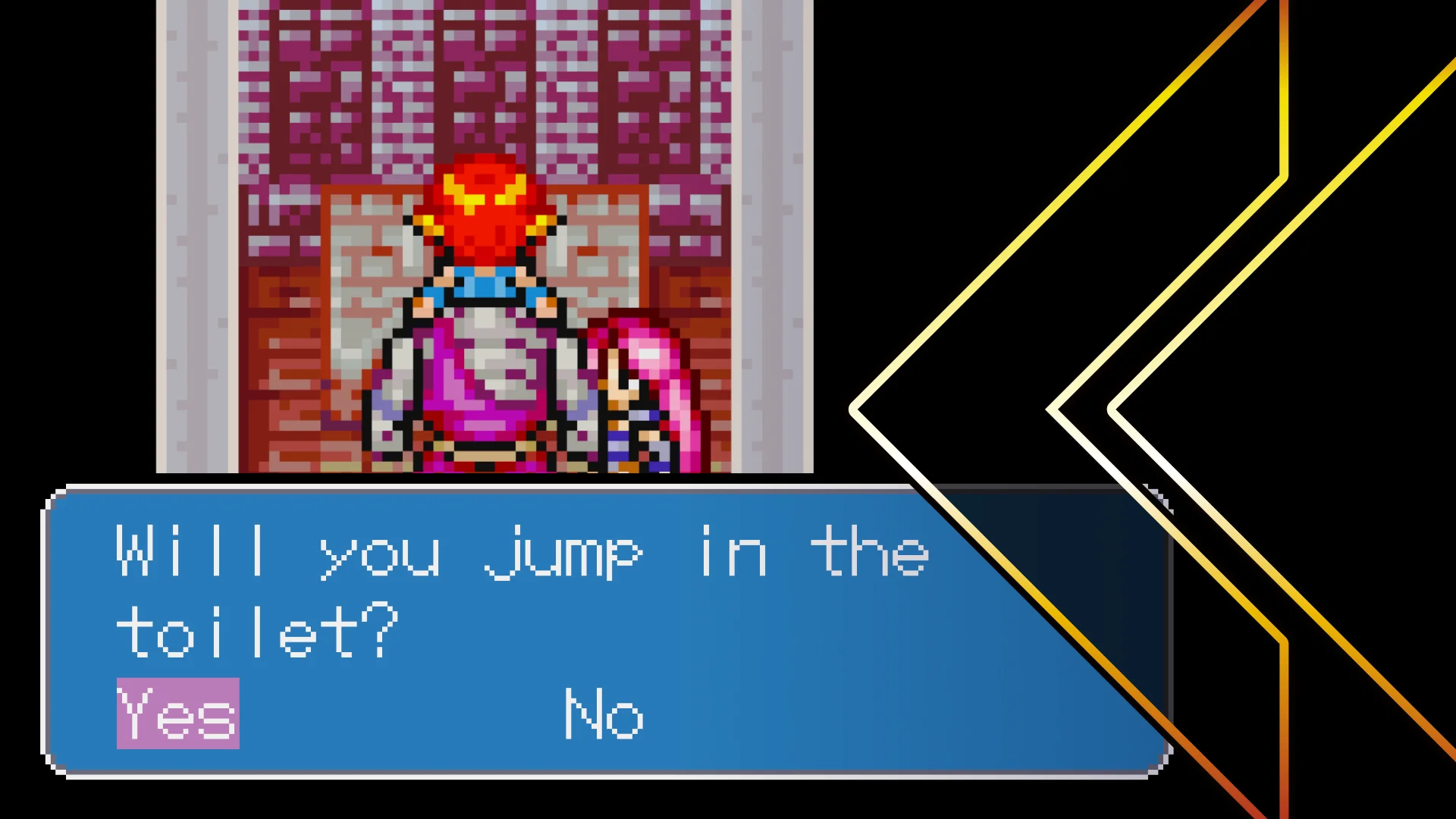

More than its cover lets on, Breath of Fire II is a surprisingly thoughtful game in terms of its ambitious narrative themes and its overambitious gameplay developments. It’s also incredibly thoughtless and frustrating at times. I found myself repeatedly checking its release date—yup, 1994 in Japan!—due to all the ways it lags behind some of its more long-lasting contemporaries in terms of music, localization, and dungeon and quest design, but also in the ways it took bold swings with mechanics that would later become RPG staples.

An auto-battle button. Day-night cycles. Morality systems. Town building. The ability to debrief with each party member after major story events. Though these were often half-baked ideas, the foundations were there for real advancements in the genre. Was this really the same game that forced me to walk all the way out of completed dungeons with random encounters every third step?

But for every moment Breath of Fire II made me want to pull my hair out, it made me laugh with its characters, it made me well up when I lost those characters, and it made me breathe a sigh of relief after a white-knuckle boss fight. I’d heartily recommend its opening and closing hours to even a newcomer like me, and I guess those middle bits are all right if you can get the retuned GBA version.

Mike Salbato

When I signed up for this episode, I wasn’t sure where my Final Thoughts would land. I have so much nostalgia-based love for Breath of Fire II, absolutely, but would I still enjoy playing the game today, decades after the last time I adventured with Ryu and crew?

I’m pleased to say that I did, even if the localization was a smidge worse than I remembered, and that’s saying something. But even a sometimes incomprehensible localization doesn’t obscure some legitimately interesting story beats, along with gameplay ideas and innovations that we take for granted now, but were not standard in any way in 1994. Logically speaking, that last part is something I couldn’t have known in 1994. Numerous big and small things like the “trade” option in shops, the town building, and the fascinating-but-flawed Shaman system have all been done since, usually better, but other RPG devs weren’t doing them at the time! The folks who made these early Breath of Fire games were ahead of the curve in some ways, and I’d never have realized that without revisiting this game.

Would Breath of Fire II be leagues better if Capcom re-released it with better dialogue and much better EXP, gold, and encounter rate balancing? 100%. But even through it all, the characters are all memorable and several story beats still land well today even through the rough localization — the tonal shift in Evrai still gave me chills.

The newest aspect of Breath of Fire II, for me, was playing it alongside a fellow old-school fan and someone new to the game, and I’m so glad I had the opportunity to play and chat about it with Zach and Matt for the show.

Zach Wilkerson

Of all my core childhood games I’ve spinned up again for Retro Encounter, Breath of Fire II was the one I was most trepidatious to try again. My memories simply didn’t match the discourse surrounding the game. The localization wasn’t that bad, right? The grind, surely, couldn’t be as tedious as people say. What about the story? I loved that as a kid.

Interestingly, despite all my concerns, I still love Breath of Fire II. Okay, maybe not as much, but I was struck by how many things the game does remarkably well, and sometimes for the first time. Auto-battle is simple, but it makes the grind less painful. Building up a town might be weirdly limited, but it’s still fun to fill it out with people around the world. It’s way too easy to get knocked out of Shaman form, but it’s a great concept.

I’m still most struck by the story, though, and not just because it was the game that opened my eyes to the very concept of religious corruption all those years ago. It’s often clumsy, but there are so many moments that still stand out here: the opening prologue, Ryu’s sprint toward the final boss and the odd things he calls you along the way, and the general melancholy that permeates the world. Everything just feels a little off, a little strange, and the localization might actually help with that at times? It’s that feeling that stuck with me for all these years.

It all comes together to create a deeply flawed but oddly interesting RPG that might not have the polish or staying power of its contemporaries, but I still love wholeheartedly.