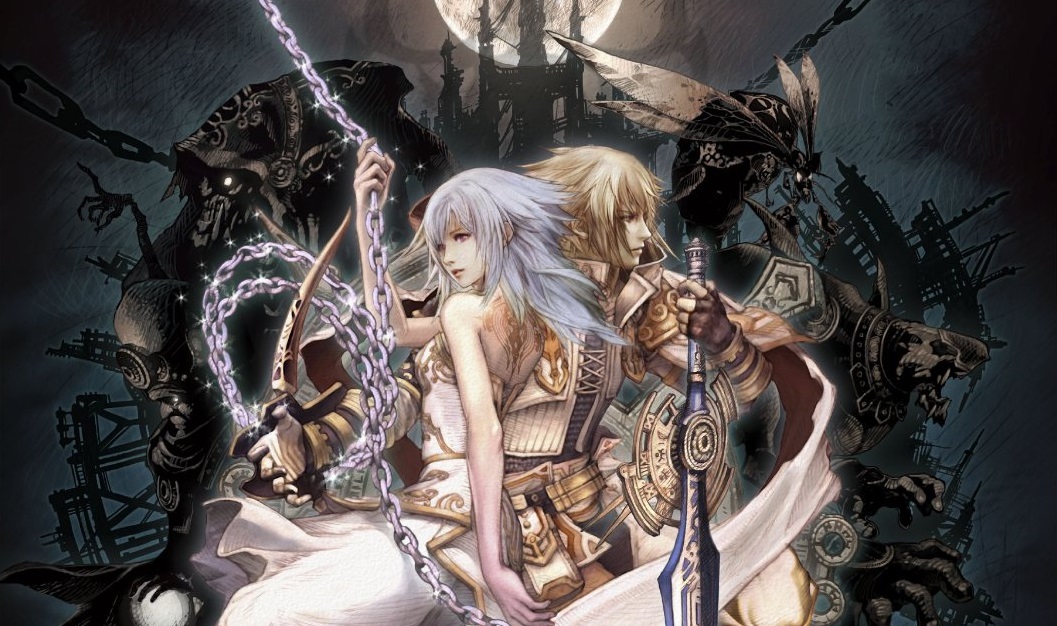

Upon beginning Pandora’s Tower in earnest, one soon uncovers many thought-provoking themes like gender roles, religious vegetarianism, loyalty, and more. As the plot progresses, the wider mysteries of the world promptly fall into the background. The game’s more intimate themes do far more to capture the imagination and inquiry of the player than the setting’s political backdrop or why the earth is being held together by colossal chains connected above a vast abyss. Actually, that last one is pretty cool.

As I’ve yet to finish this Wii-exclusive action RPG at the time of writing, I will not reveal much about the conclusion the game reaches about these topics. I find that’s not the point since grappling with and exploring the themes within my mind has been satisfying—and even challenging—already. When I started to play Pandora’s Tower, I never thought it could have this effect. Therefore I hope you’ll forgive me for making this writing a little bit more “me”-centric than usual. In the past, I’ve tried to base my articles on history or some sort of political philosophy that I find allusions to in these wonderful games, but this one will be a little bit more personal.

That makes me quite uncomfortable. So let’s get started.

Gender Roles as Usual

The story begins with Aeron, a soldier from a kingdom, and Elena, a citizen of the kingdom Aeron’s kingdom is fighting against. The love story between them begins with Aeron getting injured in enemy territory and Elena finding him and nursing him to health. The war eventually ends, and in the tense peacetime, Elena receives the honor of singing at the harvest festival in the city. As she’s in the middle of her song, she’s suddenly struck with a curse that rapidly transforms her body into a grotesque, tentacled monster.

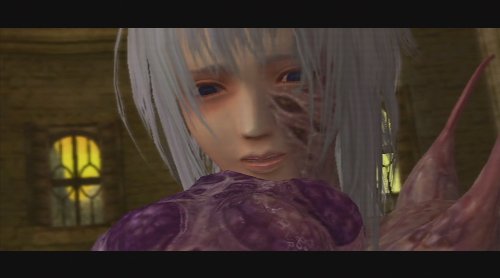

Pandora’s Tower has a “T for Teen” rating, but these transformations are genuinely gnarly. Tentacles sprout from her shoulders, desperately feeling the air around them as if rapaciously seeking sustenance or a surface to traverse, her skin develops an outer coating of reddish flesh, and everywhere Elena walks, she leaves a trail of ooze almost like a slug would.

Here the game introduces its major persistent mechanic, managing Elena’s curse. With the help of Mavda (one of the most creatively designed characters I’ve ever encountered), Aeron and Elena escape to a forgotten observatory overlooking The Scar, a great gash in the earth over which, suspended by thirteen titanic chains, looms a massive structure made up of thirteen towers. As you enter this ancient complex, you can kill monsters, collect their flesh, and bring it back for Elena to eat.

The flesh temporarily staves off the curse and reverses the transformation Elena has suffered. Her curse worsens in real time, meaning the longer you wait to return with monster flesh, the further along the transformation will be. The later stages are tragic, as her unrecognizable face greets you with a twisted smile, and she asks how you’re doing. If you give her flesh in this state, she’ll jump on it like a cat pouncing on its prey, whereas if you give it to her while she still has her wits about her, she’ll hesitantly eat it in one of the most unnerving cutscenes I’ve encountered. With shaking hands, she puts it to her lips, and gags on the first taste. Eating meat violates her religion, so the moral question becomes: to what degree would you sacrifice your values or beliefs to save yourself?

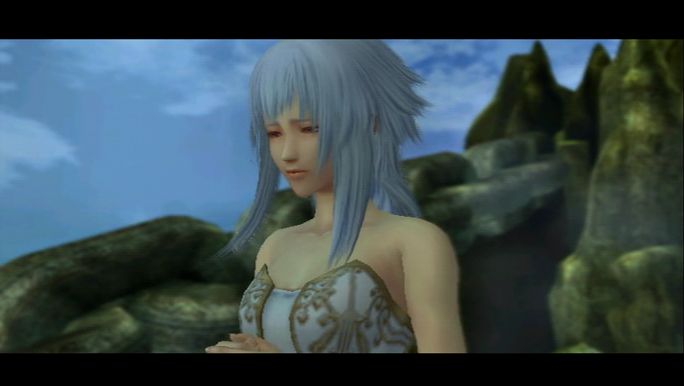

Before that, I was struggling within myself with the question of whether or not Elena’s transformations were made more disturbing by her nature and character design. You can already imagine who this woman, the love interest of the protagonist, is. She fits very comfortably in the realm of a woman supposed to appeal to a straight young man. Thankfully she’s not sexualized in the way these characters can often be, but she is very delicate outside and inside. As a character, she’s sweet, thoughtful, and personable. On the outside, she’s pretty. She’s meant to evoke from the player a desire to protect or save her.

I grapple with the fact that this works on me. I wonder what it says about me that I became so invested in Elena and her well-being and found myself charmed by her dialogue and character quirks to the point of giving myself away to the feeling of wanting to protect her. On the one hand, it sends an unfortunate message. On the other hand, for who she is, she’s a well-written, likable character.

For example, giving her gifts and chatting are mechanics that affect your relationship with Elena, because of course this game has that. When I found a lamp and saw that she put it on the table when I got back to the observatory, it just made me feel good. When I talked to her about it and she said how pretty it was and how grateful she was that I found it, I found it endlessly charming. In this horrible situation, facing despair and destruction of her body and psyche, she still seems to appreciate the small beauties of life. Indeed, perhaps it’s because of the uncertainty of her future that she has this sweet and hopeful perspective.

The overall approach is unfortunate since Pandora’s Tower doesn’t attempt to do anything different from the age-old formula of the damsel in distress. Elena is even a housekeeper, augmenting the decor with items you give to her. She’s also a caregiver, having been the one who nursed you back to health after your battle injury and constantly asking about your well-being despite her being the one cursed to die a creeping and violent death. However, it’s very, very well-executed. So much so that it makes you wish this story weren’t already told a million times before. At least the twist of the deforming transformation is a bit different.

The Value of Life, the Price of Belief

What most immediately jumped out at me when starting this game wasn’t the relationship between the main characters so much as the relationship they have with their beliefs. There is a real misfortune in Elena betraying her belief that she shouldn’t eat meat to keep herself alive. Without knowing the details of this particular doctrine, it’s hard to know whether there is a process for penitence or an exception to the statutes and commandments of this religion. Whatever nuances exist or don’t regarding this issue, Elena is distraught about it, so at least she takes it very seriously and only hesitantly agrees to it.

There is a complicating factor here as well, just like there are complicating factors in the beliefs and strictures of real-world religions. This is not a simple issue of personal devotion but has a much wider effect. If Elena were to refuse to eat the beast flesh (including the master flesh of all the boss monsters in each tower to achieve a permanent cure) and allow her transformation to proceed to completion, she would cause great harm to everyone around her. She can’t sacrifice herself in pious martyrdom because that could result in a monster powerful enough to dismantle her society, thrusting it into an earthly hell.

So the righteousness equation is thoroughly disrupted by the harm that following the rule would bring. Is it more righteous or less for her to sin in this way? Without intimately knowing her religion, we can’t say. We can, however, address our own beliefs thusly.

Loyalty to Heaven, the State, and the Lover

One thing that the game communicates clearly about is a hyper-romantic version of priorities in loyalty. Aeron falling in love severed his loyalty to his comrades in arms, his government, and his land. Elena, in part, likewise severed her loyalty to her faith for a chance to fulfill her love of Aeron.

Of course, many other factors compel her to break that heavenly law of eating flesh, but clearly her relationship with Aeron is also a significant contributor.

It’s beautiful, if cliche, to imagine circumstances in which one would alienate themselves from every structure in their life for love, but were this to happen in real life, chances are it would be a tough pill to swallow.

I’m reminded of the 2006 film Tristan & Isolde, a film whose lesson about the destructive power of blind, thrashing “love” I find wonderful. Tristan loved Isolde so much that he was willing to, as the king’s trusted associate, betray him through actions that eventually led to the downfall of his society and the unknowable suffering of thousands of innocent people. Is love that important? Well, if it disregards basic love for all humans, methinks it ceases to be love and becomes something else.

The situation in Pandora’s Tower is quite a bit different. The factors are all different, and the love between the characters is not destructive but is in fact a platform that can save the world and society from the monster Elena would become. Also, the minuscule consequences of Aeron going AWOL disappear in the grand picture of the politics and tensions between the nations, so that betrayal does not hold a candle to Tristan’s.

Please don’t misunderstand me. I love the idea that love can conquer all. It’s just a cliche worth dismantling and examining. I’m glad that the love displayed in Pandora’s Tower also factors in the health and happiness of the rest of the world, not just the two lovebirds.

So Yeah

I’ve been loving Pandora’s Tower. In many ways, it seems to be the least talked about of the three legendary “Operation Rainfall” titles, which is understandable especially in the face of the mighty Xenoblade Chronicles. Still, I’ve been surprised at the heart and depth this game has. Playing it is pretty fun too, but more intriguing are these questions and the persistent management aspect of the curse. Seeing the different states Elena can be in depending on how negligent you’ve been is mechanically dynamic and emotionally sad. The game handles the questions it asks about belief and loyalty with care as well. I’ve felt strangely enriched playing Pandora’s Tower, and I can’t say that about many games.