“Games shouldn’t be political.”

“The main character being a woman/person of color/queer isn’t realistic.”

“Sad, they’re pandering to SJWs/Woke gamers instead of focusing on making games.”

You’ve probably heard one or all of these “critiques” of games and developers who try to be inclusive. Whether it’s on social media, in the comments section of a YouTube video, or a message board, there are always people who loudly insist that video games should be fun escapism and nothing else. But those of us who belong to one or more minority groups often understand why representation in video games is important and needs to be done well.

As an aromantic and asexual woman, I don’t often see myself in the media I consume. Even in 2022, it seems to be difficult for creators to do right by the more well-known segments of the LGBTQIA+ community, and the apsec community is particularly invisible and misunderstood by the general population. Every day, I see people insisting that asexuality isn’t real, or that it is but it’s a medical condition, or that asexuals don’t experience enough oppression to be queer. It’s all so very…exhausting.

So on those few occasions when a video game or a TV show includes an ace character and does a good job, I feel seen. I feel understood. These are powerful feelings, but if you’re wondering why they’re such a big deal, consider that our society presumes that we are cis and heterosexual. We’ve made great strides to combat that presumption, but the fact is that cisheterosexual is still considered the “default” experience. This is what we mean by the term cisheteronormativity, and it’s so pervasive that you may not even realize that you benefit from it if you are cis and straight. It’s easy to take this sort of thing for granted, but only if you don’t exist outside of the “norm.” Those of us who do have to struggle to be seen and heard, and this is precisely why representation is important.

To illustrate this, let’s look at a few asexual characters that demonstrate how diversity can enhance a gaming experience and push back against the cisheteronormative assumptions our society struggles to overcome.

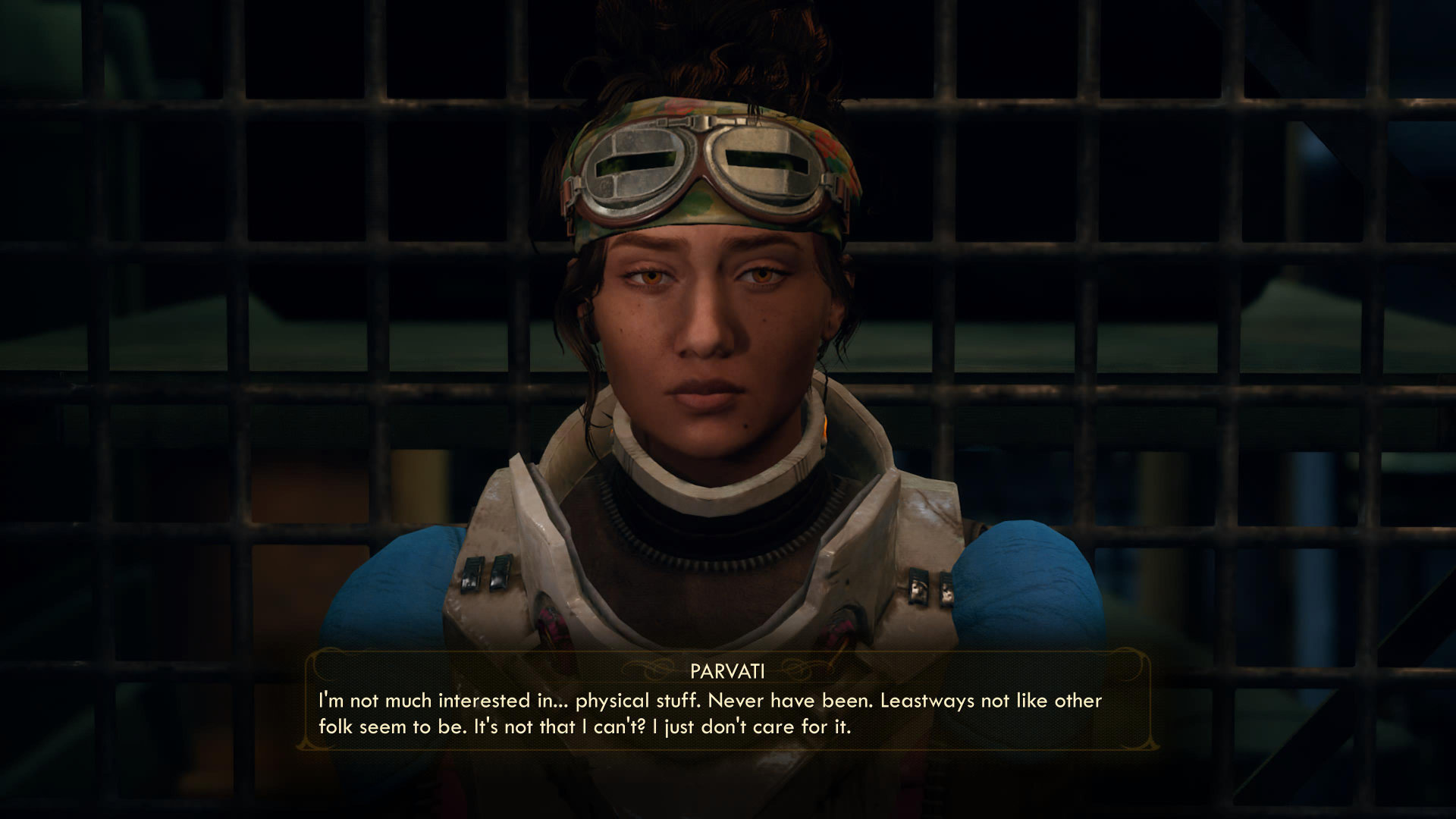

Parvati Holcomb from The Outer Worlds

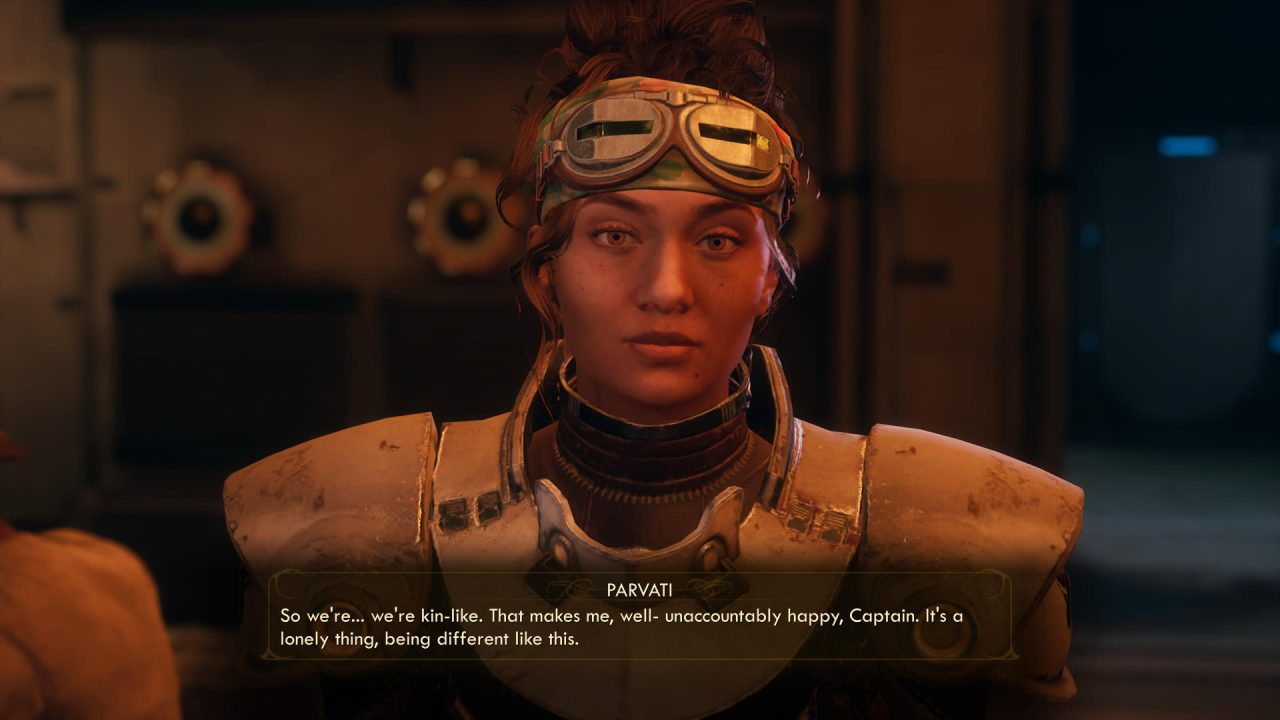

Parvati is almost instantly endearing. She’s nervous but genuine. She’s brilliant but lacking in self-confidence. She’s a kind soul, but she would follow you through hell itself because you’re her captain and she trusts you. It’s basically impossible not to like Parvati.

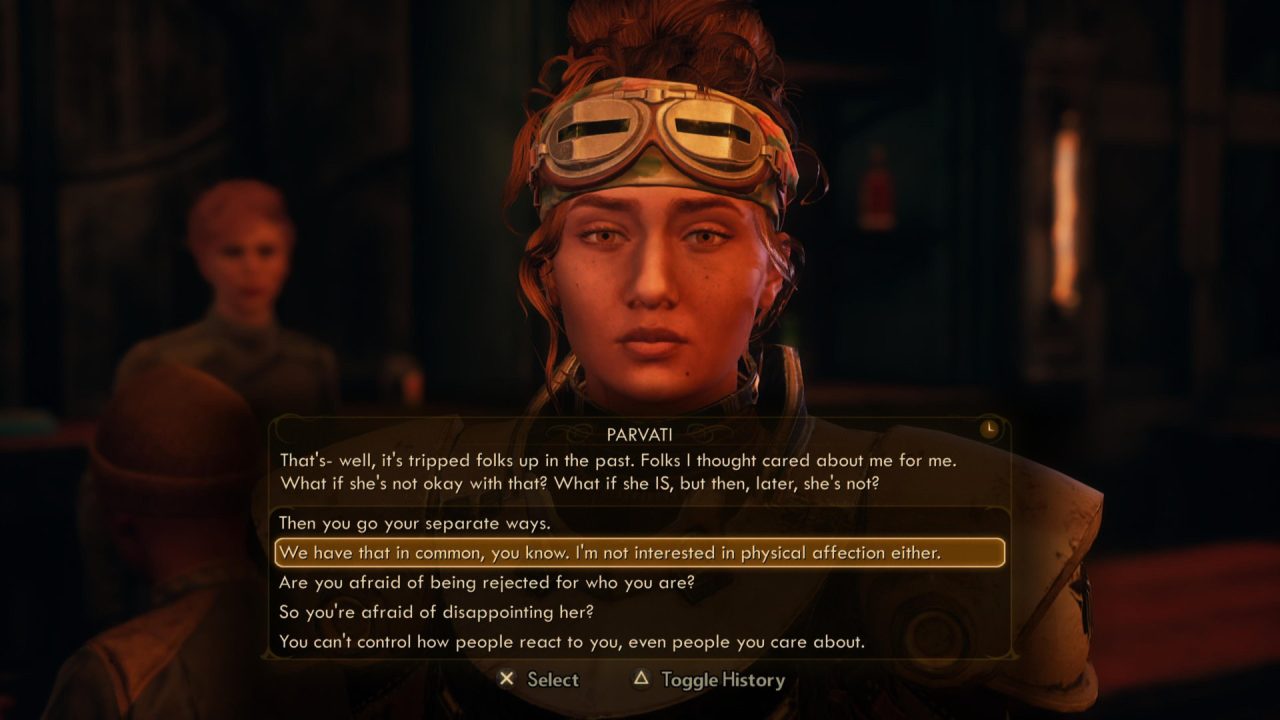

After you travel to a massive ship known as the Groundbreaker, Parvati strikes up a friendship with its captain, Junlei Tennyson, that eventually becomes something more. While you help Parvati navigate the confusing and nerve-racking realm of asking Junlei out for a date, she reveals to you that she doesn’t much care for the physical aspects of relationships. This has led her past partners to call her cold, and she confides in you that she’s worried Junlei will lose interest in her if she doesn’t engage in sexual intimacy. You can encourage her to talk to Junlei about this and remind her that she won’t really know if her feelings will be a dealbreaker for the relationship unless she gives it a shot. You also have the option of telling Parvati that you feel the same way she does about sex, to which she responds with immense relief at the revelation that she’s not alone in feeling the way she does.

Neither Parvati nor the player character ever use the word asexual, but Parvati’s (and optionally the player character’s) experiences are absolutely asexual in nature. At this point, it would be helpful to point out that asexuality (and aromanticism, for that matter) is a spectrum. The defining feature of asexuality is experiencing little to no sexual attraction to others, but asexuals can and do differ in how little attraction they experience; some may have very specific circumstances where they do feel attraction. Parvati doesn’t really talk about sexual attraction, but presumably she doesn’t feel it that much because she’s not interested in sex in general.

That’s another aspect of the asexual spectrum, by the way. Some aces are entirely sex-repulsed and will not engage in sex under any circumstances. Others are sex favorable and may engage in and even enjoy sex. Still others are in the middle: they’re not interested in sex and may not truly enjoy it, but they may engage in it if their partner wants to. Parvati falls into this sex-neutral category, and her past experiences reflect some of the challenges real-life aces deal with when they date allosexuals (people who experience sexual attraction).

Her fears about being rejected by Junlei because she doesn’t want to have sex also reflect a harmful societal norm that aces constantly have to deal with: the idea that romance and sex are inextricably linked and that to have the former, you have to have the latter. This is allonormativity (the idea of sexual attraction and sex as being “normal”) at work, and it negatively affects asexuals who either feel like they will never find a loving partner or are told by others that their only choices are to either live and die alone or to have sex.

Parvati was designed to be asexual from the very beginning by writer Chris L’Etoile, but shortly into development of The Outer Worlds, L’Etoile left Obsidian and Kate Dollarhyde took over writing the character. Dollarhyde put her own experiences as a biromantic asexual woman into Parvati’s dialogue and player interactions with her. The result is an authentic experience that appeals to many people, regardless of their own orientations.

I, of course, can’t speak for everyone who has played the game, but as a member of the ace community, I found those moments that Parvati confides in the player to be incredibly special and almost surreal. I had been out for several years by the time I played The Outer Worlds, but I had never seen a video game character so accurately and effortlessly reflect my own lived experiences, and I certainly hadn’t had the opportunity to openly identify as my orientation in a game before. It might seem strange to say this because I know many fellow aces through social media and other online connections, but Parvati felt like a reaffirmation that my life as an asexual is valid. It’s not that I didn’t think I was valid before meeting Parvati, but there was something powerful and reassuring all the same about interacting with a character who was not only openly ace but unambiguously intended to be ace.

Interacting with Parvati also made me wonder how her identity would have impacted me if I hadn’t already known I was ace. Part of my coming out experience included a realization that I had been ace for a long time but had only recently learned how to explain that existence in a way that didn’t make me feel like something was wrong with me. If I had still thought I was straight when I talked with Parvati, maybe I would have realized that her experiences mirrored mine, and that could have helped me understand that I wasn’t broken — I was just ace.

This is the other reason why representation matters. It’s not just important because it reinforces that queer identities are valid and normal, but also because it can help people like me who’ve spent part of their lives assuming they were straight realize that they really aren’t. How much confusion and distress could I have avoided if I had met a character like Parvati in high school or college and realized I was ace at a much younger age? My guess is a lot. And I know there are plenty of young people out there who feel exactly like I felt whose lives could be better given just a little push to help them understand they are perfectly right and whole just the way they are. Queer characters like Parvati can be that push. They can be the light that brightens a dark room and turns something amorphous and frightening into something clear and comforting.

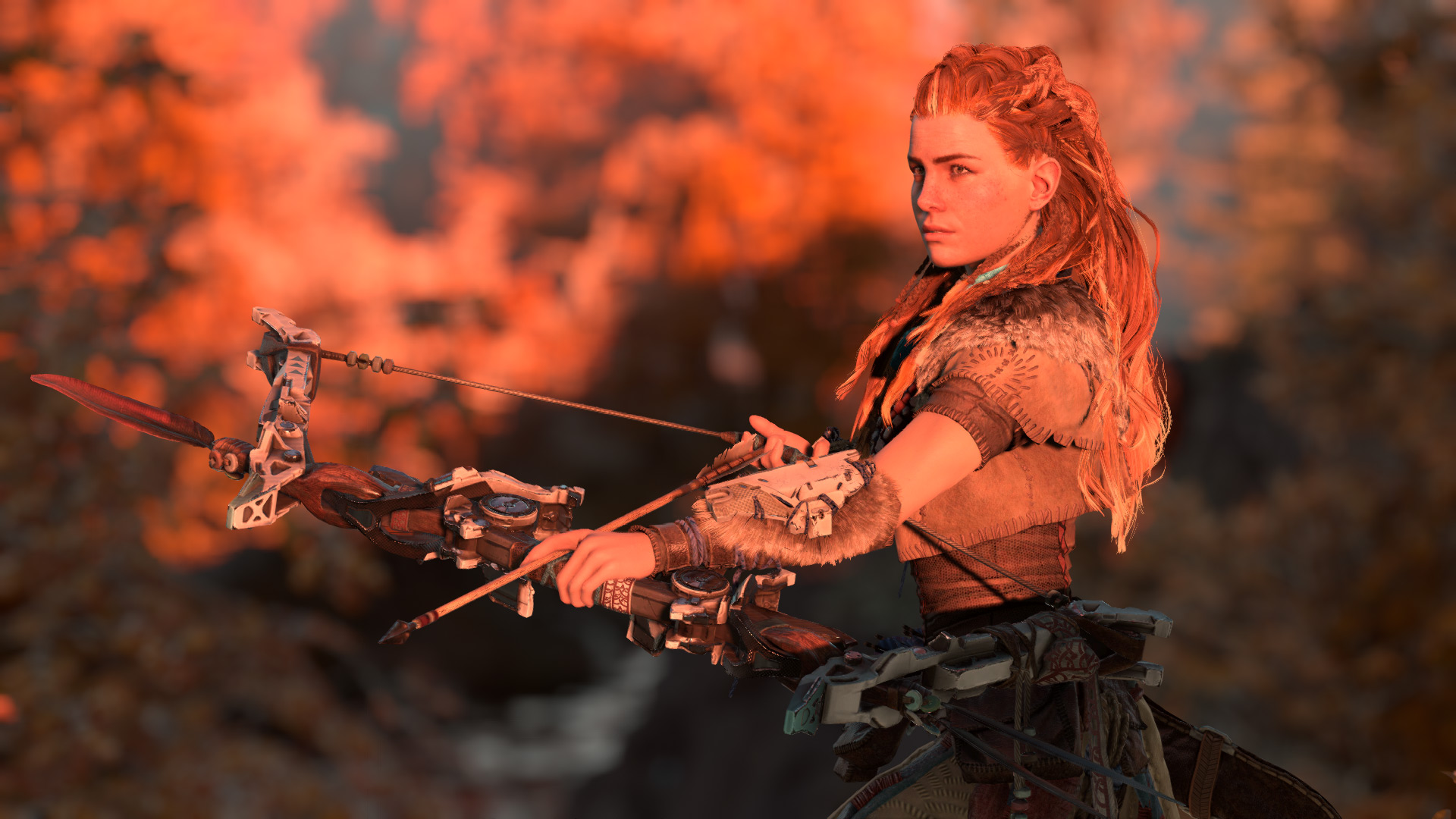

Aloy from the Horizon Series

Right off the bat, I’m sure that some readers may wonder what Aloy is doing in this feature. Aloy isn’t ace, right? She definitely had the hots for Varl or Talanah or Petra, right? Well, yes and no.

When it comes to queer representation in media, we don’t always have the benefit of characters who are unambiguously LGBT+ — that is, characters who are intended to be read as queer by their creators. There are plenty of characters whose orientation is never overtly revealed, and sometimes that may be by design. Developers may decide that a character’s orientation isn’t relevant to their story, or they may want to leave it up to interpretation so that as many people as possible can see themselves in said character.

Aloy is one such character. To my knowledge, Guerrilla Games has never indicated any intended interpretation of her sexuality, though they’ve certainly created many characters that Aloy could potentially be interested in, and fans have shipped her with most of them. I don’t mind any of these interpretations, and I think there’s plenty of material in the games that can support them. In fact, if Aloy is not aspec, I definitely like the idea of her with several of those fan-favorite NPCs. But both Horizon Zero Dawn and especially Horizon Forbidden West present Aloy as almost entirely focused on her mission, often to the detriment of her personal relationships. And it’s not that hard to interpret this focus as being at least partially the result of a lack of interest in romantic and/or sexual relationships.

For example, Horizon Zero Dawn has a well-known scene where Aloy turns down a proposition from Sun King Avad after his paramour dies, and players can choose to be gentle about it or viciously shame the man for attempting to use her as a rebound when there are more important things to be worried about. And in Horizon Forbidden West, there is a scene that immediately stood out to me as an aroace woman. Midway through the game, Varl asks Aloy for advice about his romantic relationship with Zo, and Aloy very pointedly responds, “What makes you think I know anything about any of this?” Of course, Aloy could mean that she herself has no experience in this area, but it’s easy to read this statement through an aspec lens. At least, it is for someone on the spectrum like me.

You may think I’m cherry-picking here, and to a certain extent, I am. But to be fair, that’s unavoidable when you’re talking about a character whose orientation is not explicitly stated, either in game or by the developers. The point isn’t to argue that Aloy is unquestionably ace but rather that she could be interpreted as ace. Of course, this kind of representation isn’t as ideal as characters who are unambiguously intended to be queer, but it’s no less important. Remember, people who are LGBT+ usually don’t have the luxury of their orientation being assumed by default in the absence of explicit evidence. We also have less representation across the breadth of fiction in general, so to a certain extent, all forms of representation are valuable, even if said rep is ambiguous. After all, even in real life, people don’t go around telling everyone their orientation, yet we all know people who we think could be queer. This is really no different.

It’s also important to remember that Aloy could be ace and still be romantically interested in one or more characters. While not favored by all queer individuals, the split attraction model says that romantic and sexual attraction need not be the same. A person can feel romantic attraction for one or more genders but not feel sexual attraction to anyone, and vice versa. In this way, even if you interpret Aloy as being romantically interested in one of her companions, it doesn’t automatically mean that she can’t also be asexual.

Am I trying to have my cake and eat it too? Perhaps. I will admit that a queer interpretation of Aloy is important to me because Aloy herself is such a fantastic character. She’s a strong female lead in a highly regarded AAA franchise, and even in 2022, we don’t see that often enough. The idea that Aloy could be not just good feminist representation but also good queer representation is, in some ways, a dream come true.

And if her particular form of queerness could be considered asexual and/or aromantic, that’s huge for the aspec community and me as an aroace woman. Remember, we’re not very well known or understood, even within the larger LGBTQIA+ community. And as hard as it can be to find good queer representation in video games, most of the current good rep is of the more recognizable segments of the community. Counting such a recognizable character from a well-known franchise as potential aspec representation is meaningful for a community with only a handful of confirmed characters that represent their unique queer experience.

Again, this goes back to why representation is important. We live in a world where developers still justify male leads by claiming that female leads do not sell as well, and that’s just the same sexism we’ve been dealing with for centuries rearing its ugly head in a new medium. The struggle for queer rep in video games is comparatively more recent, and despite the progress we’ve made over the last few decades, it feels relatively difficult to achieve — particularly in light of recent backsliding in the U.S. when it comes to things like trans rights.

If at any point in this section it seems that I’m reaching or even twisting things to suit my desire to see Aloy as ace…well, I suppose you’re not entirely wrong. Like I said before, this is kind of unavoidable when a character’s orientation is ambiguous. But if you understand all this and find yourself taking issue with my interpretations, I’ve got some harsh truths for you.

As I said before, we as a society still assume that being cis and heterosexual is the norm. So much so that we still presume that a character is cis and straight until proven otherwise. Sometimes that “proof” is obvious: the character states their orientation or behaves in a way that is unambiguously queer. But when the “proof” is not straightforward, society views them as cis-hetero by default. How, then, are we meant to show that the character is or could be queer?

The simple truth is that we have no choice but to reach, to read into statements and behaviors, and to argue for an interpretation that is not definite but still possible. Like I said before, we don’t have the luxury to assume that everyone else sees what we see in a character. That is a privilege reserved for cis-hetero individuals in a cisheteronormative society, and one of the ways we can combat both is by pointing out ways in which the human experience can diverge from the so-called “norm.” And we can do that by saying, “Hey, I think there’s an argument for this character being queer, and here’s why.”

Is every argument for a character being interpreted as queer a good one? Of course not. I don’t mean to imply that justifications for a queer interpretation are never a stretch. But I do not think this is the case for Aloy, and that is why I chose to include her in this feature. The sad fact is that if we limited a discussion of ace representation in video games just to those characters who are unambiguously aspec, well, we wouldn’t have nearly as much to talk about. So it’s important to include characters we think could be aspec, and I hope I’ve shown how Aloy can fit in that category.

Now that we’ve gotten this discussion of whether Aloy could be aspec out of the way, let’s talk a little about how her being ace could affect a player’s experience with the Horizon games. I do not want to speak for everyone, of course, but I found it refreshing that the games don’t shove romance or sex at you: partly because it allows for the ace interpretation I’ve been discussing, partly because optional romances in video games aren’t always well done, and partly because it’s nice to have a female character who isn’t at least partially defined by who she snogs.

As an aside, I’m aware that there is a feminist critique of the Horizon games that argues it is sexist that Aloy isn’t allowed to express her sexuality as a woman when the odds are she would be given the opportunity if she were a man. That is certainly a valid criticism, and on the one hand, I do find myself agreeing with the sentiment purely from a perspective of unequal treatment between men and women. On the other hand, I often feel that we put too much emphasis on romance and sex in general, to the point that it is perceived as a required part of the human experience when it really isn’t. In that sense, even if Aloy turns out to be canonically allosexual, she’s still fighting against the presumption that romance and sex are the norm, and that’s still valuable for those of us who are aspec.

Commander Shepard from Mass Effect 3 and the Inquisitor from Dragon Age: Inquisition

So we’ve talked about Parvati, a character who is unambiguously intended to be ace, and Aloy, whose sexuality is ambiguous but could easily be interpreted as ace. The final side of the triangle, as it were, are characters where player choice determines their sexuality. And what games come more immediately to mind in this category than BioWare’s Mass Effect and Dragon Age series?

First things first, I am well aware that the BioWare style of romance — particularly in the early days of each series — was not exactly without issues. Mass Effect, in particular, was notorious for making its somewhat awkward sex scenes act as the romance’s conclusion, as if the goal of any relationship is to have sex and then you’re done.

Despite legitimate issues like this, there is arguably still value in BioWare’s games and others like them for the aspec community. Not because you can choose a relationship, but because you can choose to abstain from one entirely, and neither the game nor its characters mistreat you because of it. True, none of these games let you have your character explain why they’re not shacking up, meaning their reasons are once again up for interpretation. But as I’ve already described, ambiguity is something we just have to deal with when it comes to the search for ace representation.

Having said that, Mass Effect 3 and Dragon Age: Inquisition are slightly different from the other games in their respective series. They both allow you to romance a character and then explicitly choose to forgo sex. Technically, the first Mass Effect lets you abstain with the right dialogue choice, but that results in you pumping the breaks on the relationship until Saren is dealt with and your love interest leaves the room. By contrast, in Mass Effect 3, they stay and cuddle with you in a short but touching scene that is arguably just as intimate as if you had gone ahead and done the nasty. I remember being pleasantly surprised that this was an option, and I was happy that the way they incorporated it didn’t make you feel like you (or the love interest, for that matter) were being punished for choosing not to have sex.

Dragon Age: Inquisition does something similar with some of its romances. Dorian’s is probably most notable because you can explicitly turn down sex with him, leading to a particularly intriguing conversation. Dorian mentions that in Tevinter, where he was born and raised, intimate relations between men are only physical — in other words, it’s just about sex and nothing else. By turning down sex with him, you can indicate your desire to have an emotional relationship with him — either in addition to sex or without it, depending on how you want to roleplay your character. Not only is this a fantastic option from the perspective of asexual representation, but it’s also a commentary on the problematic viewpoint that being gay is just about sex, a stereotype that the gay community has long fought against.

As a brief aside, Iron Bull provides a similar option for those wishing to roleplay their Inquisitor as aromantic (but not ace). The relationship starts with sex, and the player can opt to keep it purely physical, making it a friends-with-benefits arrangement. Iron Bull also mentions that the Qunari “don’t have sex for love,” which makes them similar to how Tevinter views gay relationships, but whereas Dorian’s romance gives you the option to reject sex in favor of “a relationship,” Bull lets you reject romance in favor of keeping things purely sexual. Of course, both relationships can be both romantic and sexual — there’s no either/or requirement — but it’s still nice to have the options, especially because past BioWare games tended to treat romance and sex as inextricably linked.

Last but not least, it’s worth pointing out that if players romance Josephine, they don’t have an explicit option to have sex with her. There are dialogue choices the player can make that imply the relationship is or will become physical, but since you can avoid them, it is possible to headcanon the relationship as purely emotional. Unlike Dorian’s romance, however, the player is not given the option to reject the idea of sex outright, so this one requires a little more offscreen roleplay to make it fit as aspec representation.

At this point, you may be wondering why I waited so long to talk about these characters. After all, there seem to be many good roleplay options in these games for aspec players. Well, the issue — for me, anyway — is simply that: they’re options, not the default experience. Customizable characters and dialogue options are excellent tools for making a hero and a playthrough unique to each player, but they’re kind of double-edged swords as far as queer representation is concerned.

The positives are obvious. Having relationship and dialogue options allows players to roleplay their character as any of a number of different sexual orientations. This is wonderful for players who might not otherwise see their orientation represented in games all that often, and it means that one character can appeal to multiple players with different identities. Gay, lesbian, bi, aro, and ace players can all potentially see themselves in Shepard or the Inquisitor, in other words.

On the other hand, these same qualities can make this kind of representation less than ideal. The optional nature of dialogue and romance choices means there’s no definitive version of the main character. Shepard and the Inquisitor can be 100% straight, after all, and even though there are options you can take to headcanon them as ace, it’s not quite the same as if it were a universal experience the developers intended the player to have. I’d even argue that while most players are aware that Shepard and the Inquisitor can potentially be queer depending on how they are roleplayed, the possibility of them being aro and/or ace likely does not occur to many outside of the aspec community.

Part of this is simply because the aspec community is not well known or understood, even within the larger LGBT community and certainly not outside of it. But part of it is that these options exist within relationships that are otherwise sexual or romantic, and even though you can use them to not have sex or engage in romance with a character, they’re not explicitly ace or aro in nature, so they may not read as such to allosexuals or alloromantics. Players can choose these options for reasons other than that they’re roleplaying their character as being aspec — maybe Shepard just really doesn’t want to have sex right before the final showdown, or the Inquisitor thinks that Bull is really freaking hot but doesn’t see him as a romantic partner. It’s just not the same as Parvati in The Outer Worlds, who tells you in no uncertain terms that she’s really not into sex and only wants romantic relationships.

The other negative with this kind of representation is a little meta: basically, it’s about completionism. I’m not necessarily talking about the 100% completionist mentality, though that certainly is a factor since games with optional romances usually include achievements as a reward for “completing” the relationship. What I mean is that, by their very nature, video games encourage players to complete them. Whether this means doing all the things or just most of the things, we’re meant to engage with a game’s various systems, and optional romances are one of those systems. Even if none of the options appeal to a player, they may feel obligated to pick one so they can have “the full gameplay experience.” Yes, this is a FOMO thing, and yes, it’s silly, but games have gotten very good at conditioning us to treat them like checklists. “Here are all the things you can do in our game, and you want to do all of them, right?”

You may want to roleplay Shepard or the Inquisitor as being ace, but there’s no unambiguous asexual romance and abstaining entirely might make you feel like you’re missing out on content. There’s also the fact that we still live in an allonormative and amatonormative society, and even if you’re asexual and/or aromantic, it’s hard to escape the pressure that places on you to engage with romance and sex on some level. (Trust me, it’s hard. I still deal with it even though I’ve been out for years now.) So you look at those romance options that let you avoid having sex, but they’re open to interpretation and require you to headcanon an explanation that other players may not consider or even agree with. It’s just…not ideal.

Of course, even though it’s not ideal, it can still be valuable. As I mentioned earlier when discussing Aloy, ambiguous representation — or perhaps I should say representation subject to interpretation — can still be useful. After all, if we limited ourselves to unambiguous characters, we’d have a lot less representation to talk about, and the aspec community in particular needs as much rep as possible. As long as we are aware of the inherent weaknesses in these kinds of characters, we can still celebrate their strengths. And in recognizing what these characters can mean to the aspec community, we may encourage developers to take that extra step and include more unambiguous representation in future games.

In Conclusion

I’ve said a lot in this article. And I usually write too much, but this is a lot a lot. So to quote a certain exasperated priest in Spaceballs, what’s “the short, short version?”

To be blunt, it’s that asexuals, like every other community that falls under the larger LGBTQIA+ umbrella, need more representation in all forms of media, including video games. I’ve talked about three forms of representation and discussed several examples. There are more I could mention, but the pool of asexual or potentially asexual characters in video games is severely limited. We’re often overlooked by developers, just as we are in real life, even among the larger LGBTQIA+ community. And that’s a shame because the aspec community is diverse and interesting, and just like our homosexual, bisexual, and pansexual allies, we challenge the idea that heterosexuality is a necessary part of the human experience.

In fact, asexuals take things a step further and challenge the assumption that sexual attraction and sex are necessary for a healthy and fulfilling life. As crazy as it may sound, you don’t need either to be a perfectly happy and whole human being. If you think you do, it’s mainly because our society is very good at convincing us that sexual attraction and sex are inextricable parts of the “normal” or “natural” human experience. Media plays a huge role in that socialization process, and even video games contribute to our perception of what is normal. So the more asexual representation we can get, the more we can shift perception to a place where both allosexuality and asexuality are seen as the norm. That, in turn, can help already out aces feel accepted and understood, and help those questioning their sexuality more easily come to terms with the idea that they may be ace.

I likely won’t change the minds of those who believe that representation in games is intrusive and unnecessary. Indeed, I would be surprised if such people were still reading this article, to be honest. But that won’t stop me from arguing for it, and it shouldn’t stop others from fighting for it, either.

Asexuals exist, and we aren’t going anywhere. Asexuals are valid, and we’re just as normal and healthy as every other allosexual orientation. Asexuals are inherently LGBTQIA+, and we deserve the same rights and protections the larger community seeks to secure. Representation in media, including video games, is one way we can normalize all of these facts and achieve equality. And even if you’re not LGBTQIA+, more representation only increases and enriches the narrative experiences you can have. Variety is the spice of life, as they say. In that sense, asexual representation — indeed all queer representation — can only be seen as a win-win for everyone.

Let’s celebrate asexual characters in games, and encourage developers to create more. Because the future is inclusive, and no matter what the gatekeepers and bigots say, asexuals are going to be a part of it. So let’s shuffle the deck, deal out a hand, and see those aces!