Warning: Spoilers for Final Fantasy XIV: Endwalker

Before even starting my Final Fantasy XIV: Endwalker MSQ experience, I had to cope with some disappointments about patch 6.0. As much as I wanted to, I couldn’t bring myself to like the new changes to my main job, Monk. As you can probably tell from the headline of this article, I’m not about to use the next thousand words to complain about Monk, though: I’ve already made my peace with that (at the time of publishing, they’ve fixed a few of my issues with it). My character has put down the gloves and picked up a scythe.

Like many others, I chose to level the new Reaper job before completing the Endwalker main scenario quests, which definitely framed my perspective on Endwalker as a whole. I could list countless aspects of Endwalker’s main narrative that personally connected with me or dissect the way it brings together its themes of searching for meaning in a meaningless world wonderfully. However, when I decided to dedicate this piece to the game, the thing I felt I could most passionately write about was what I’ve spent the most time with: the Reaper job. My thoughts on Final Fantasy XIV’s Reaper feel particularly entangled with my understanding of Endwalker as a whole, anchoring my understanding of this sweeping conclusion to a decade-long saga to the Reaper. This figure ultimately represents a lot of the same ideas that Endwalker approaches: endings, searches for meaning and the inevitability of change.

With the Reaper job, Final Fantasy XIV takes a broad swing at transforming our understanding of a (Grim) Reaper into a fun class with a unique gameplay style. Looking closely at the details that make up the Reaper, it’s also an interesting case study in the ways games reinterpret mythology into aesthetic and gameplay features, which in turn contribute to the rich “mythology” of the title in question. In both gameplay and narrative, Final Fantasy XIV provides a dynamic and often flawed reimagining of the Reaper, one that ultimately resonated with me in unexpected ways as I witnessed my Warrior of Light walk to the end.

What Can the Harvest Hope For?

It’s appropriate that the Reaper would be introduced as a job in Endwalker, an expansion story that focuses both literally and thematically on endings and how endings ultimately shape meaning in our lives.

Across a broad spectrum of separate mythological beliefs, the “Reaper” or “Grim Reaper” — otherwise known as “Death” — is an ethereal figure associated with the ending of human lives. It’s a little unclear where the Grim Reaper originated as an idea. The most popular rendering of Death as we might understand him today — as a skeletal figure in a black shroud and wielding a scythe — begins with artwork based on the biblical depiction found in the Book of Revelation. As one of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, Death was one of several figures that signified the biblical end times as the personification of one of life’s only certainties. When contrasted with his more nebulously defined companions — War, Pestilence and Famine — there’s no doubt Death stands out as a particularly imposing figure. Their skeletal nature reminds us of our ultimate fate, and their scythe is a symbol of a “harvest that is yet to come.”

Many cultures have either separately formed or adopted a personification of death that bears similarities to the singular overarching concept of the Grim Reaper. The Mexican folk saint Santa Muerte (or as their full title loosely translates, Our Lady of the Holy Death) is a deity figure that frequently appears as an iconic personification of death in many areas of Mexican culture, depicted principally as a protective figure who guides souls safely to the afterlife and shown visually as a female skeletal figure wearing a shroud and holding a globe. Poland’s personification of death, Śmierć, has a lot in common with the idea of a Grim Reaper but eschews the black shroud that many versions usually go for in favour of a white garb. You’ll find many versions of the Reaper throughout the world with both small and large differences.

As one of life’s only certainties, contextualizing death through mythology, culture and representations in art is a necessity. This is why the idea of the Grim Reaper has taken hold in so many different cultural and artistic contexts and generally continues to reappear in the media we consume. If you’ve played a video game in the last 10 years, you’ll likely have encountered some personification of death, the Grim Reaper or something inspired by these ideas.

In Final Fantasy XIV, we get less the Reaper as a solitary personification of death or omnipresent force, but more a “reaper” as a dark toolset of otherworldly powers that your Warrior of Light can utilise to become a kind of reaper themselves. This power is something that can be taught and learned, democratizing the ability to harvest souls. Whilst this concept is not something that frequently appears in cultural myths of death or the Grim Reaper, it’s certainly an idea that recurs in pop culture, which routinely offers depictions of the Grim Reaper as a kind of mantle that is passed on, or in some cases, a literal job (see: Terry Pratchett’s Discworld version of Death).

The foundational flavour text of XIV’s version of the Reaper also offers a starting point rooted in labour, prodding at both the symbolism and literal function of the tool that is often used to conduct said reaping: the scythe. The original reapers of Final Fantasy XIV are farmers from Garlemald, who in defense against a threat choose to take up arms and call upon a dark power:

“Forced north into the frigid mountains, the survivors sought a means to tap into the reservoir of aether otherwise closed to them. A daring few found their answer within the void, binding themselves to its creatures to gain verboten power ─ power fed by the souls of the slain. Once more they took up their scythes, this time to reap a crimson harvest.”

The final sentence of this flavour text offered by the game’s official media tells us a lot about how the writers of Final Fantasy XIV perceive the particular brand of Reaper they’ve created. “Once more they took up their scythes” conjures the image of farmers transformed by this otherworldly power from the void, with the scythe acting as the commonality between their old lives and their new lives as Reapers who seek “a crimson harvest.”

In many ways, it makes for a humanizing detail that despite gaining the power of the voidsent, they’d continue using the scythe as a weapon out of a sense of familiarity. There’s a reason that describing the Final Fantasy XIV Reapers as “edgy botanists” caught on in the community, and it’s not a particularly bad description of how the Reapers of XIV are stylised. In making the Reaper into a job that anyone’s Warrior of Light can take on, the Reaper has to shift from a lone mythic figure into an ability shared between many.

As “edgy botanists” or “demonic farmers,” the Final Fantasy XIV version of the Reaper forms a unique if slightly muddled identity, but one that feels particularly suitable for the Endwalker expansion. This is an identity that is gradually expanded upon through the job quests, existing lore and even the mechanics of the class.

Don’t Fear the Reaper

The Reaper job is unlocked and explained in a short series of job quests from levels 70 to 80. I would describe these quests as melodramatic, occasionally funny and surprisingly light on the kinds of details that I initially expected from them. The Reaper job quests tell an abbreviated tale focused on the themes of family, revenge and what it means to embrace a dark power for a good cause. They don’t tell a particularly amazing story, but they elucidate an interesting understanding of Final Fantasy XIV’s version of the Reaper and how it corresponds and contrasts with real-world Reaper mythology.

Having heard of your exploits as a legendary adventurer, the character Drusilla offers to give you guidance in the art of becoming a Reaper, lending you a scythe and teaching you how to awaken the powers of your very own voidsent. What follows is a story of Drusilla’s personal quest to take down Orcus, a voidsent being who has possessed the body of Drusilla’s grandfather (who, notably, was once an assassin who attempted to take on Emet-Selch). If there’s one thing these Reaper quests make clear, it’s that Orcus is a dangerous being that must be stopped, and the voidsent can’t be trusted. Furthermore, it’s asserted that the voidsent powers that Drusilla and her band of Lemure Reapers use are a dangerous tool that exposes them to mortal risk. It is made clear that Reapers only existed as a means to defend their homeland in Garlemald, but have since taken on the broader responsibility to protect the world from voidsent threats.

Despite their risks, the powers of the void are both nebulously defined and normalised amongst the Reapers we’re introduced to in the questline. Some further understanding is offered by the terminology that appears in other areas of Final Fantasy XIV lore. The void and the voidsent seem to correspond to a demonic underworld and the demons in it, respectively. The Lemure Reapers seem to embrace this power willingly, even in spite of their repeated assertions that it’s dangerous to do so.

There is fear associated with Orcus from all the members of the Lemure clan. Orcus represents the ultimate danger of making a pact with a voidsent: losing complete control over one’s own body and becoming just a vessel for a demon. Why then does Drusilla so willingly lend this power to you, the Warrior of Light? Why do they use some form of it themselves if this is a possible result?

The Reaper quests don’t provide interesting answers to these questions, but one distinction is clearly drawn: there is seemingly little fear in “tapping into” the power of the voidsent for what the Lemure Reapers believe is a righteous cause. As Drusilla describes it, they use this power to “kill those that need killing” and ask the Warrior of Light to do the same for the “betterment of the realm.” They speak of “worthy prey” and piercing the void to undo the “singular brand of wickedness” it has unleashed upon the world.

Drusilla also has no reservations about the Warrior of Light using this demonic power, despite that the Warrior of Light is a stranger to them initially. The opening quest makes it clear that Drusilla perceives a “killer instinct” within the Warrior of Light that would allow them to wield the powers of the void, and that giving the Warrior of Light access to this power is based on an unspoken trust. Drusilla alludes to the fact that embracing such power leaves no hope for the “sanctity” of one’s soul. “You’ll dance with death and return as its envoy,” she says without hesitation, acknowledging the risk but giving the power away with little precaution.

In addition to the idea of the Reaper as a transferable power, the moralisation of embracing such power is probably the most significant difference between the Reapers of Final Fantasy XIV and the Grim Reapers of classic mythology. Traditional personifications of death and the Grim Reaper don’t necessarily position the figure as a force for evil, but rather a genuinely neutral entity — an inevitable arbiter of the end that arrives for all people, good or bad.

This isn’t exactly the case in Final Fantasy XIV. Even if the Lemure Reapers themselves appear slightly morally dubious, Reaper powers in the hands of the Warrior of Light could be understood as nothing more than a tool to help them achieve morally good acts, especially when we consider the narrative at large. The Reaper questline ends with Orcus, the evil voidsent, defeated. The story’s main focus ultimately leads the Warrior of Light to save reality in unthinkably important ways, and if they’re a “Reaper” whilst doing that, it stands to reason to suggest that one can act out of moral obligation as a Reaper in Final Fantasy XIV‘s world.

However, the powers of the voidsent can be taken on by any character in the world of XIV. In this way, the Reaper as a “job” itself has a kind of amoral quality, which could be seen as similar to the amoral nature of mythological personifications of death. It’s not the death-dealing powers of the scythe or the void that matter in this context, but rather how these powers are used that dictates if the Reapers of XIV’s world are good or bad on an individual level.

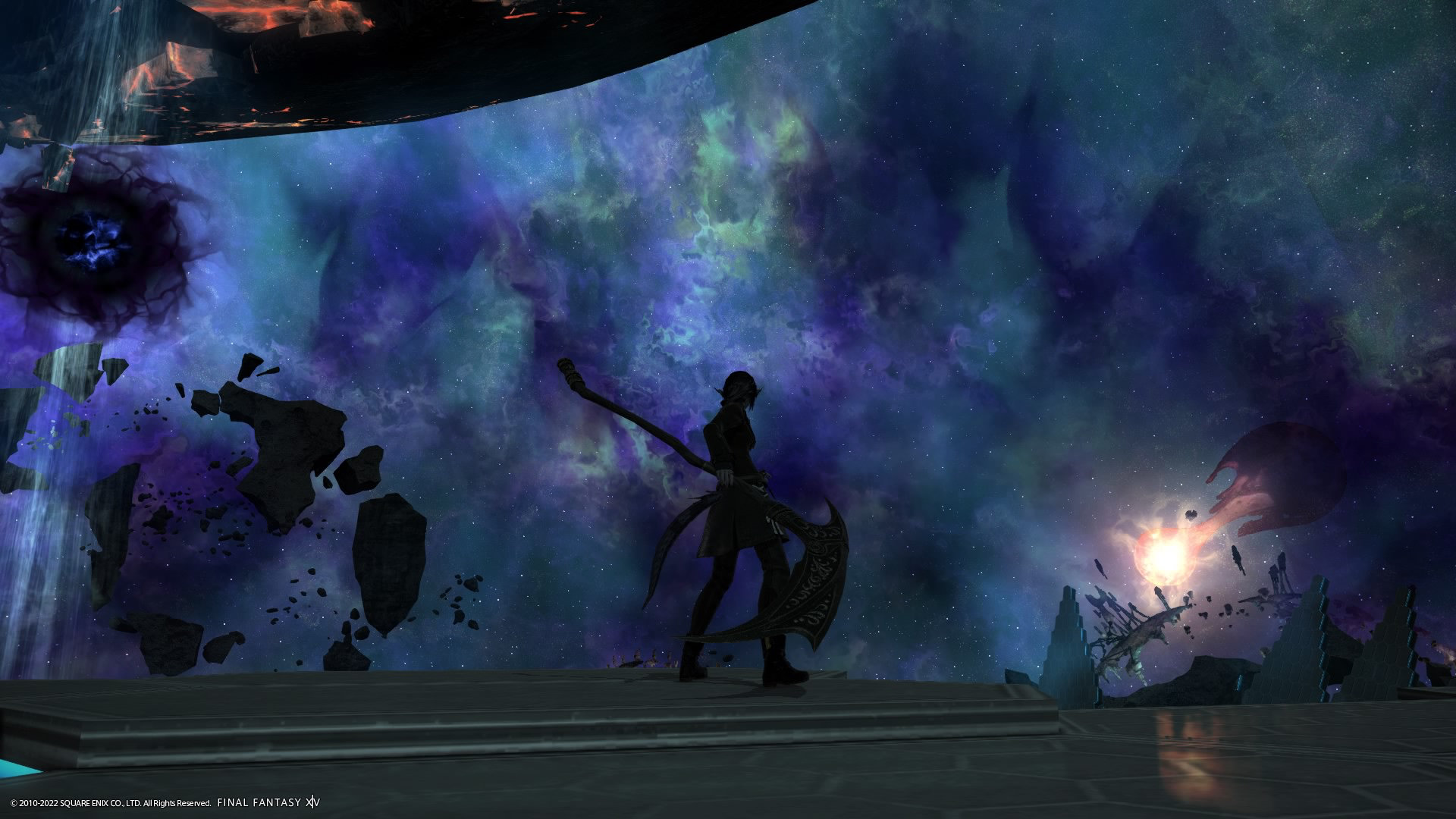

In the narrative of Endwalker, the character of Zenos forms the antithesis to the Warrior of Light in a number of ways, but if both wield a scythe and a voidsent avatar in the final battle, they make for an interesting point of comparison. This supposedly corrupting, dangerous power is being used by both parties in this scene, yet both are ultimately “in control” of their actions and using their scythes and void powers for their individual agendas.

Once more, Final Fantasy XIV’s Reaper asserts its own identity and posits an obvious departure from the supernatural force it’s based on.

Reaping What You Sow

Outside of narrative detail, the identity of the Reaper as an “independent force for change” is shaped substantially in a variety of other ways, from the visual design to the gameplay. Even small things like the types of gear you can equip and the animations of attacks feel thoughtfully considered in constructing a clear identity for the job.

One of the easiest things to latch onto is the design of this voidsent avatar that augments itself onto your Warrior of Light. The creature itself is reminiscent of a distorted version of a Grim Reaper. It has elements of a ragged black shroud, a pronounced skeletal form underneath it and a slicing attack that arcs like the curve of a scythe’s blade. When they appear, they also bring with them an otherworldly aura. There’s something deeply unsettling about the avatar’s appearance, but it’s notably familiar in these Grim Reaper-esque traits.

The Reaper job’s burst attack, activated by the skill enshroud, also grants the Warrior of Light signifiers of a more traditional Grim Reaper look. This form is explained as the voidsent avatar assuming some form of direct control over the Warrior of Light’s body. Apparently, this possession is the kind that creates clothing out of nothing, giving your character a hood, some glowing eyes and that same otherworldly aura that the voidsent avatar has.

Even in the job’s relative infancy, the gear and scythes available for the Reaper do a good job of representing some of these same iconic elements in unique ways. As someone who spent some time looking at a lot of artwork of the Grim Reaper’s various interpretations in preparation for this piece, it’s certainly fun to see the iconic elements incorporated into XIV gear.

If we think laterally, the gameplay of the Reaper job itself also communicates some level of textural detail. As with all DPS jobs, it’s a swift dance of pressing the right keys at the right time. Optimise your damage by building meters and unleash a powerful burst attack at the perfect opportunity. It’s certainly familiar, but that familiarity allows it to embody the idea of “reaping.”

If you set up your positions well, you’ll reap the results. If you build up your meter efficiently, you reap the results. As with all DPS classes, your damage output won’t be the same if you play inefficiently. Playing the Reaper job well is all about managing meters, timing and your position; in a figurative sense, what you “sow” with the Reaper will determine what you “reap” in terms of damage output later on in your rotation. This perhaps seems like an odd place to make a connection, but some interesting ideas spring up as a result of understanding the Reapers of XIV as reapers in the most literal sense of the word.

Unlike many of the Grim Reapers of mythology, however, the Reapers of Hydaelyn do not have some inherent caretaker responsibility for the souls of the world. Instead, the souls exist as a currency to fill up a meter, which is used to bolster the Reaper’s power further.

In terms of translating the mythological concept of a Reaper, as with the narrative details surrounding the job, we return to the idea of individuals with Reaper powers and no inherent responsibility to go along with them. Just as the ideological conflict between a Reaper Warrior of Light and a Reaper Zenos reminds us that being a Reaper here is a distinctly amoral endeavour, the gameplay reminds us that being a Reaper in this world is a role where one is, perhaps selfishly, playing with the powers of voidsent and death without being held accountable for it in the way that a more traditional Grim Reaper might.

Instead, the sowing and reaping done as the Reaper in a combat context are a means to an end: a DPS regime conducted to get the enemy to zero HP. This in itself tells us a lot about XIV’s Reaper, which despite eluding easy classification, could be once again described as a tool for bringing about change.

The End and the Beginning

I was given a tarot reading when I was around 12 years old. I’ve never been a particularly spiritual person, and I barely understood what tarot was at the time. It wasn’t a particularly notable experience, except for one card draw. Right at the end of the session, the card drawn was Death. It featured an illustration of the Grim Reaper. I was immediately shocked, thinking this meant I would die in the near future, perhaps horribly.

Of course, anyone experienced in divining tarot cards knows that Death is not necessarily reflective of the recipient actually dying. Instead, the Death card is intended to indicate great change, a shift in direction for one’s life.

I write the last section of this essay deep into an exhausting move to the other side of the world. I don’t know what awaits me in the future, and with that uncertainty comes a certain level of anxiety. But in equal measure, there is also comfort in going through such changes, knowing that there is the potential for a lot of happiness in those changes.

Endwalker clearly deals with the idea of endings. It’s the end of a 10-year saga about an epic struggle between light and darkness. However, it’s also about new beginnings. In this way, we might suggest that the story of Endwalker is itself concerned with change and moving from one phase to the next, not unlike the symbolic message of the Death card.

To view the Grim Reaper as a symbol of such great change is to understand them as an immovable event in the future. In the same way that we all face the end of life, we must face the inevitable forces that change our lives from one paradigm to the next. Endwalker itself is full of such paradigm shifts. It frequently questions what the place of people is in the inevitable cycles that make up our lives and in the life of the universe in which we live.

Although there is a lot more to say about the thematic detail of Endwalker‘s Reaper, it’s best to understand the Reaper job as another candid reminder from Endwalker to embrace endings with open arms. This doesn’t mean giving up, but rather acknowledging that with every seed sown, there is a swing of the scythe to reap it.

The Reaper, in all its forms, is a tacit acknowledgement of this premise. XIV‘s Reaper strays far from the idea of a “skeletal arbiter of death” to quietly embrace this more encompassing and thematically relevant idea of the Reaper as a force for change. Every ending yields the bountiful possibilities of a new beginning, so we shouldn’t be afraid to walk the dark, unknown paths that lie ahead.