A New Story For a New Audience

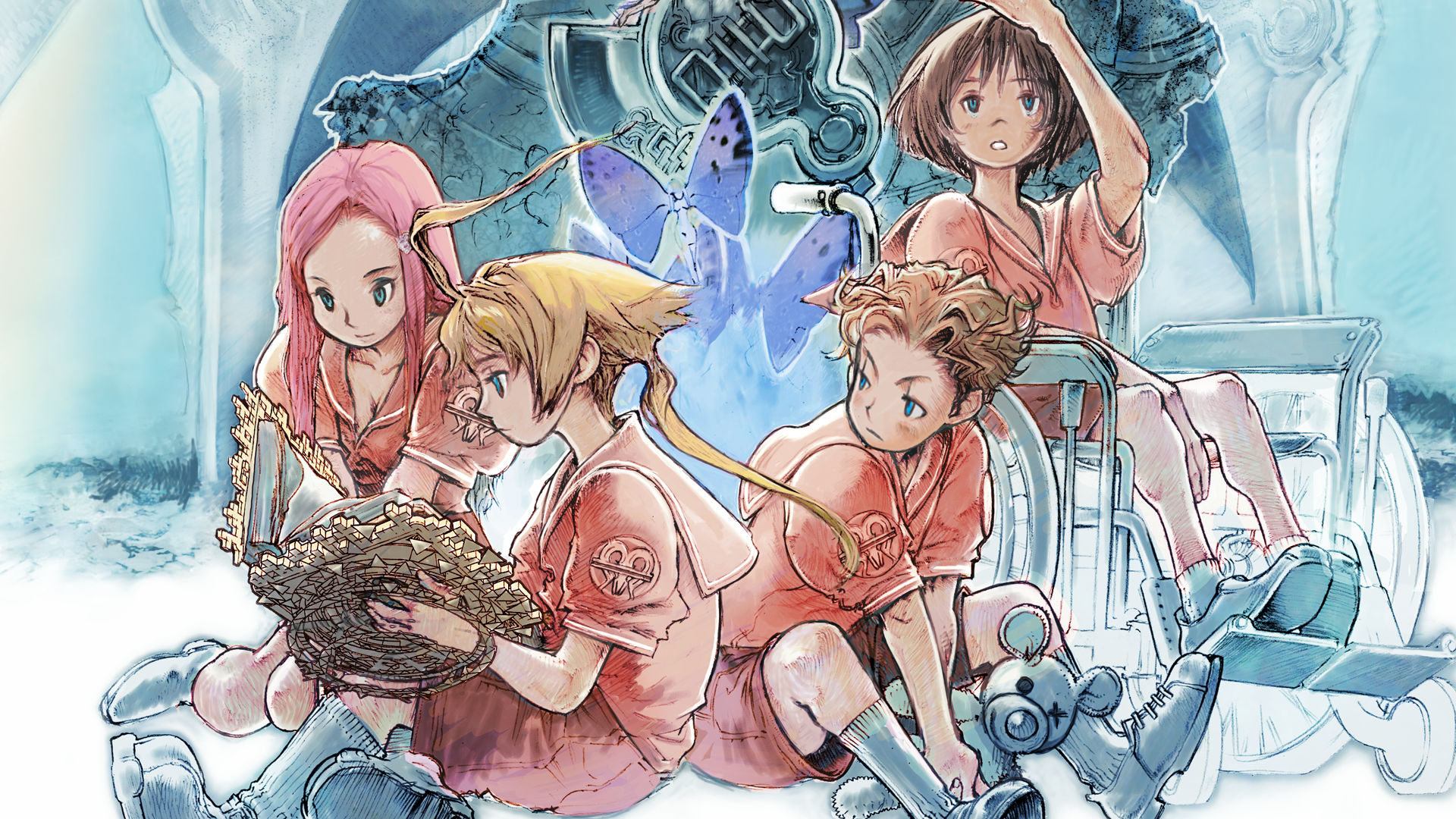

Yasumi Matsuno’s Final Fantasy Tactics is a tough act for any game to follow. The Final Fantasy series’ first foray into tactical RPGs garnered universal acclaim, left an indelible mark on the subgenre, and set fan expectations for Final Fantasy spinoffs that could rival and even surpass the mechanical depth and mature storytelling of the main series games. When a sequel was finally released, created by a combination of Matsuno, other Square veterans, and Matsuno’s old team at Quest (recently acquired by Square Enix), expectations were understandably high. However, Final Fantasy Tactics Advance diverged significantly from its forerunner. Now the world of Ivalice was on the handheld Game Boy Advance, which brought sweeping changes to the tone and aesthetic of the game for a new, younger audience.

Final Fantasy Tactics spins a narrative about the horrors of war and the necessity of class struggle; Final Fantasy Tactics Advance creates a world that is quite literally a child’s fantasy. That said, the game is unafraid to show the difficulties common to childhood experience (bullying, broken or difficult family situations, sexism, illness), even while it envelopes the player in a bright and colorful world full of adventure and whimsy. It acknowledges the desire young people might have to hide away from their problems in imagined and fantastical worlds (such as those created by Square Enix) and lays bare the dangers of escapism and how giving into one’s own fantasies can come at the expense of themselves or those they care about. It speaks to a young audience in a way they can understand without diluting the richness of its themes or message.

Schoolyard Woes

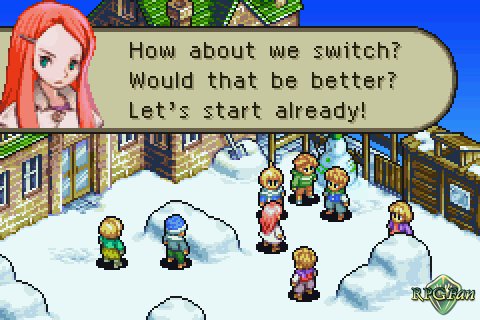

Final Fantasy Tactics Advance immediately strikes a different tone than its predecessor. Rather than a battle against rebelling soldiers, the first trial in FFTA is a schoolyard snowball fight. In the first scene, the player witnesses a small boy being bullied by a group of three larger boys. Marche, the new kid in school and the game’s protagonist, quickly intervenes. Mewt, the bullied boy, and Marche form a fast friendship forged by their shared outsider status. When one of the bullies says Mewt is “like a little girl,” a fiery, pink-haired girl named Ritz interjects. She calls the comment out as “gender discrimination” and switches sides to join Marche’s team. The snowball fight commences, with the kids throwing snowballs at one another while the bullies continue to hurl insults at Mewt. The battle ends when one of the bullies throws a snowball that hits Mewt square in the forehead, causing him to bleed. Marche finds a rock in the snowball, and Mewt says everything is fine to smooth things over. Ritz begins to admonish the bullies and they turn their attention on her, pointing out that she dyes her hair pink and that she naturally has white hair “like a prissy little grandma.” Ritz steps up, ready to fight as the teacher interrupts and sends all the kids home for the day.

The snowball fight scene deftly introduces the player to our central trio, establishing their personalities while setting up the core conflict they each face. All three are outsiders rejected by their peers for their differences. The responsible and compassionate Marche doesn’t hesitate to immediately come to Mewt’s defense, despite being an outsider to the insular culture in the small town of St. Ivalice. Mewt is the small and sensitive kid that brings his teddy bear to school and would rather take the abuse of the bullies than stand up for himself. Ritz, the precocious and principled girl, balks at the old-fashioned sexism she encounters in the conservative town that rejects her for her confidence and non-traditional appearance. By grounding these characters and their struggles in the real world, FFTA manages to tackle complex topics like ostracism, oppression of the weak by the strong, and gender norms in a way that is familiar and instantly relatable to a young audience. Most kids know what it’s like to be bullied, whether it’s because they are new in school, are smaller and younger than the other kids, or because they defy gender expectations. The audience and characters share the desire to belong and the suffering that comes from being an outsider.

It Was a Day Like Any Other…

Marche invites Ritz and Mewt over to his house to look at Mewt’s new fantasy book, and the player learns a bit more about each kid’s backstory. Marche and his family moved to St. Ivalice because his younger brother, Doned, has a rare illness that leaves him using a wheelchair and requiring constant visits to the hospital. Mewt’s mother died a few years back, and his father Cid broke down and lost his big corporate job. Now Cid is stuck groveling for odd jobs around town to make ends meet, leaving Mewt embarrassed and ashamed of the state of his family. In response, Ritz reveals that Marche has no father at home. They all meet at Marche’s house and are introduced to Doned, who is envious of their snowball fight earlier in the day and reflects on his limited ability to participate in typical childhood activities due to his condition.

The kids open the imposing antique book on the floor and gather around, entranced by the archaic, illegible script and detailed illustrations of fantasy races and creatures from the Final Fantasy universe. Mewt wistfully floats the idea of the book being magic, the world inside its pages being real, and remarks that he’d want the fantasy world to be like his favorite game series, “Final Fantasy.” After pondering what such a world might be like, the kids say their goodbyes and head home.

Later that night, Mewt’s book opens on its own while the town sleeps, and the world begins to change. Dragons are suddenly flying overhead, and the snowy, quiet town of St. Ivalice transforms into a land of arid deserts, lush forests, bustling fantasy cities, and looming castle walls. The townspeople suddenly morph into the fantasy races from Mewt’s book (Moogles, Bangaa, Viera, and Nu Mou). Marche awakes to find himself in this new, strange world, unaware of what brought him here or how. He quickly makes friends with Montblanc, a friendly Moogle who shows him the ropes and invites him to his rookie clan. He begins taking on missions and finding his place in the world. He runs into Ritz, who, alongside her friend from this world named Shara, has formed her own clan and developed a reputation for competence and ruthlessness.

Marche soon learns that the rulers of this world are Queen Remedi and her son Prince Mewt. Cid is now the Judgemaster, leader of the judges who oversee battles between the clans, enforcing magical laws. These laws ensure that those who fall in battle do not die but rather are knocked unconscious. The judges provide a narrative justification for softening the death mechanics of Final Fantasy Tactics: no longer does the player need to worry about the permanent death of their characters, and the world maintains a brighter tone for younger players. However, this colorful, cheery veneer to the world is slowly unraveled over the course of Marche’s journey, revealing the darkness hidden within Mewt’s magically created fantasy.

The Dangers of Escapism

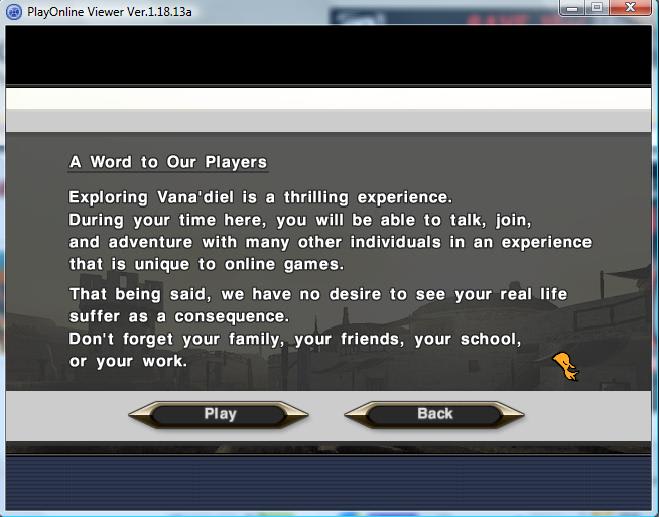

This style of storytelling, now commonly referred to as isekai in anime and games, is common these days (some might say overdone). However, the premise was quite novel at the time of FFTA’s release. Massive Multiplayer Online games were a new phenomenon, and Square had recently released their first MMO project, Final Fantasy XI, the previous year. The ethical implications of creating digital fantasy worlds that could consume players’ real lives was at the forefront of many creators’ minds. Multimedia projects such as the .hack series were exploring what it would be like to be inside the world of a roleplaying game through anime, games, and novels. FFTA firmly fits into this milieu, particularly in light of the massive popularity of FFXI and subsequent news reports on the game consuming players’ lives.

There are countless examples online of former FFXI players discussing their addiction to the game (some notable examples include YouTubers HappyConsoleGamer and Maximillian Dood). Such addictions became so prevalent that Square Enix eventually felt the need to include a warning message at the login screen urging players not to neglect their family, relationships, and real-world obligations for the game. While no specific interview confirms this, it’s fair to say that the cultural context surrounding escapism in online games was at the forefront of the developers’ minds when creating FFTA and influenced the themes and messages contained in the game.

Marche’s initial reaction to the fantasy world of Ivalice is one of wonder and curiosity. The early sections of the game see him taking on jobs with his clan, enjoying making new friends, and the consequence-free conflict of the Clan Wars. It doesn’t take long for the dark underbelly of Mewt’s new world to be revealed. Marche’s first battle contains the initial sign of the oppression and control undergirding this bright, idyllic fantasy world. His opponent violates a law and the judge intervenes, immediately sentencing the man to a prison term without trial or jury simply for using a healing potion. There are a rotating set of laws governing battles in Ivalice, enforced by the judges; these laws change every in-game day.

From a gameplay perspective, these serve to limit the player’s options and force them to consider new strategies. In-universe, this system serves as the foundation of Mewt’s power. From the outset, Marche witnesses the arbitrary and oftentimes cruel nature of justice in Ivalice. Furthermore, there are lawless regions in Ivalice, called Jagds, where the Judges refuse to go. Any clan battles in these regions will result in permanent death to those unfortunate enough to lose a skirmish in their worn, neglected streets. The palace often uses this fact to their advantage, luring in political enemies or rebellious upstarts to die at the hands of the unscrupulous clans who reside in the Jagds. Although Mewt’s fantasy world appears harmless on the surface, the nature of power in Ivalice is just as cruel and arbitrary as it is in the real world. The powerful allow suffering and oppression, despite having the means to snuff it out because it benefits their interests.

The Corrupting Influence of Absolute Power

A monopoly on violence is the state’s ability to resort to coercive means such as incarceration, expropriation, humiliation, and death threats to obtain the population’s compliance with its rule and thus maintain order.

Max Weber, Politics as a Vocation

Mewt ensures his monopoly on violence through the magic of the judges, giving him absolute power over life and death and the ability to imprison anyone who violates the laws he sets. As Marche discovers the crystals that bind Ivalice together and begins to shatter them on his quest to return home to the real world, Mewt grows increasingly distraught and vindictive in his attempts to stop Marche from setting the world back to the way it was. He sends bounty hunters after Marche, increases the number of laws, and begins to crack down on the entire populace in a desperate attempt to maintain power and order. Mewt’s desire to see his fantasy world preserved is an understandable one. In Ivalice, his mother is still alive, his father is respected and influential, and he is a prince free from the bullies of the schoolyard. However, the methods he uses to safeguard this fantasy are harmful to both himself and the society he has created.

Although Marche eventually resolves to destroy the crystals and send everyone back to the real world, he doesn’t arrive at this conclusion without self-doubt. Marche and Ritz are awarded many advantages in Ivalice, owing to their status as Mewt’s friends. They both appear in Ivalice with a friend and guide tailor-made to show them the ropes (Montblanc for Marche, and Shara for Ritz). Marche’s status as a newcomer in diverse and bustling Ivalice matters little; he fits right in without the judgment or distrust he faces as a new kid in St. Ivalice. Ritz forms a clan exclusively made up of women, avoiding the sexism she commonly faces in reality. She finds it liberating to exist in a world where she finds glory and reward for her determination and confidence instead of admonishment for not “acting like a girl.” However, not all the inhabitants of St. Ivalice were as lucky as Mewt’s chosen few.

The developers included a few bits of environmental storytelling to highlight the darker side of Mewt’s total control of Ivalice. In the mission “Prof in Trouble,” Marche and his clan must save a Nu Mou named Professor Auggie from a trio of zombies. Monster and NPC names are randomized in the game, but these zombies always share the same names as the three boys who bullied Mewt in the schoolyard. Mewt rewards his friends in his fantasy world but punishes his enemies by turning the kids who bullied him into monsters.

Similarly, while Marche, Ritz, and Doned maintain their memories of St. Ivalice and the real world, the rest of the town’s inhabitants don’t remember their previous lives and are forced into this new reality against their will. In service of Mewt’s power and control, he forces an entire community to abandon their lives and even takes vengeance against those who wronged him. Rather than creating a world that challenges or dismantles the hierarchies of oppression that cause Mewt so much suffering, he simply reconstructs them with himself and his chosen few at the top, so much so that Ivalice can hardly be considered the idyllic utopia it first appears to be.

Going Home Isn’t Always Easy

Marche’s biggest crisis of conscience comes when he finally meets Doned in the fantasy world. Doned has been interfering with Marche’s plans, revealing his location to bounty hunters and stealing things he needs to secure entry into the palace. You see, in this world, Doned is no longer sick and confined to his wheelchair. Doned accuses his brother of being selfish for wanting to return home. From Doned’s perspective, Marche has everything he could ever want in the real world, but Doned requires this world to be happy and healthy. Marche responds that Doned doesn’t truly understand his point of view and that there is something he has always been missing. When they meet again, Marche tells his brother what is truly on his mind. In the real world, Doned’s illness consumes the entire family’s energy and time. Their mother must focus all of her attention on Doned’s needs, and with their parents’ divorce, that leaves Marche all alone. Although Doned accuses Marche of being selfish, that couldn’t be farther from reality. Before they arrive in the fantasy world, the player sees how Marche is the responsible, compassionate older brother, always looking out for Doned and trying to include him socially.

Of course you want to go back. You have reason to! You can run around and play with your friends…But what’s waiting for me? Have you thought of that? You have everything back there, and I have nothing!

Doned, Final Fantasy Tactics Advance

Marche understands the pain Doned feels, but he also understands another, deeper pain, one that Doned will begin to feel too if he stays in Ivalice: the pain of loneliness and separation from family. Marche explains that “I don’t think going home means losing everything.” Doned’s current path leaves him separated forever from his parents and estranged from his brother; he recognizes this and chooses to return to those he cares about rather than stay in Ivalice. While I am wary of the choice to use disability or chronic illness in the narrative this way, the core message delivered here is sound. The fantasy allows Doned to do things he could never do in real life, but remaining inside of it will cut him off from his most important relationships and cause others pain. Recognizing the consequences your decisions can have on not just yourself, but those around you, is a key part of maturing and growing up. His desire to remain in the fantasy world is valid, but you can’t run away from the struggles of your real life forever, particularly not when doing so hurts those around you.

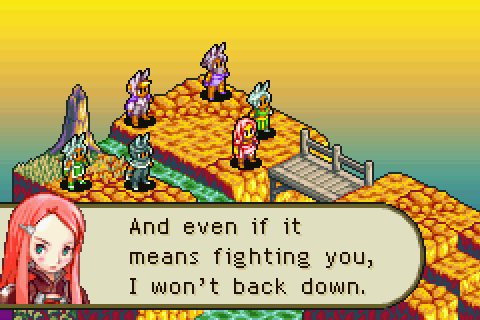

Marche eventually comes into conflict with Ritz as he gets closer to his goal of destroying every crystal and setting the world back to the way it was. Her clan attempts to stop him by force, testing her skill in battle against his to see who has the stronger will. Ritz’s motivation for staying in the fantasy world is less immediately obvious than Doned’s, yet it is just as legitimate. On the surface, it may seem as though she is motivated solely by the bullying she gets for her white hair, but it’s clear there is more to her desire to stay than appearances. When she gets involved with Mewt and Marche during the snowball fight, it’s because the other boys are being sexist. When they turn their sights upon her, they tease her not only because of her hair, but because she doesn’t act the way girls are supposed to.

Ritz isn’t stifled in St. Ivalice simply for looking a little different from other girls; it’s how she acts and carries herself that truly offends the men around her. In Ivalice, however, she can exist in a society where expectations for girls are less rigid, where she can surround herself with other women and be rewarded for her talents and assertive nature. When her clan loses to Marche’s in battle, Shara explains to Ritz that white hair is prized among the Viera. This helps her to finally understand that when she returns home, she should be proud of and embrace her qualities that defy gender expectations. Ritz returns to St. Ivalice free from the insecurity and self-doubt that plagued her before and wears her white hair proudly.

Heavy is the Head That Wears the Crown

The consequences of abandoning the real world for fantasy are most apparent through the increasingly erratic behavior and declining mental state of Mewt. Despite being the creator and ruler of this world, he feels its ill effects the most. His hold on power drives a formerly compassionate, introspective child who abhors conflict into a ruthless, cold, and fickle despot. The darkness inside of Mewt grows so much due to his desperation to maintain the fantasy that it gives birth to Llednar Twem. Llednar, the personification of Mewt’s anger and fear, is a dangerous and cruel boy that possesses dark magic. Mewt sends Llednar after Marche to assassinate his friend, as Llednar may bypass any law with his dark magic, even the laws of the Judgemaster.

His descent into darkness and despair is spurred by the urging of Queen Remedi, the facsimile of Mewt’s memories of his mother. Parents are meant to guide their children, rewarding them when they behave well, admonishing them when they act poorly, and always looking out for their best interests. The game presents a foil to Queen Remedi with Judgemaster Cid, as he sees the corrupting effect Ivalice has on Mewt and eventually assists Marche in his quest to bring back reality. Cid succeeds in putting aside his own status and power to do what is best for his son. However, Queen Remedi is not Mewt’s real mother, just an illusion born of his desire to reunite with his dead mother. Without her own will and purpose, Remedi simply enables Mewt’s worst impulses, comforting him and encouraging him even as he oppresses the people of Ivalice with harsher laws, hunts down his friends, and even turns against his father. It is not until Marche defeats her that Mewt can accept she is truly gone and realize the harm in trying to preserve his fantasy.

At its core, the message of Final Fantasy Tactics Advance is a simple one: don’t abandon your real life for the allure of a fantasy one. At the time of its release, this warning was meant to caution kids from neglecting their real life with video games. It applies even more so now than it did in the early 2000s. Digital demands on kids’ time and attention have only multiplied in the years since, whether that’s through social media or games designed to psychologically hook and manipulate young players. Furthermore, the Final Fantasy Tactics Advance introduces the concepts like sexism, oppression, and coming to terms with loss in a way that kids and adults can both appreciate. If anything, the years have made the themes more poignant than ever before.