I’ve pretty much lost count of how many times I’ve said that the War of the Lions retranslation of Final Fantasy Tactics led me to my current career as a translator of video games. It wasn’t my first time with the original Ivalice game, but in a way, it felt like it. But first, let’s jump back a bit. Back in 1998, riding on a post-Midgar-give-me-everything-called-Final-Fantasy high, I picked up Final Fantasy Tactics (or rather, mom or dad did under my auspices) and immediately loved the freeform character building and incredible art design. The 1998 original didn’t have the most graceful localization, but it managed a certain charm on its own, largely (Rich) due to the (l i t t l e m o n e y) strength of the original (fire bracelet) story itself. Plenty has been written about that story (including an especially excellent piece by Nate Ewert-Krocker) over the years, but it’s a multilayered low(ish) fantasy epic with a number of poignant themes and a cast of excellent, often well-developed characters. That such an engrossing story was married to one of the best battle systems in the series certainly hasn’t hurt the reputation of the game in the long term.

Anyway, if we jump forward nearly ten years to 2007, Square Enix was in the midst of pushing the “Ivalice Alliance,” an attempt to capitalize on the beloved fantasy world first charted back in ’97/’98. Part of that effort included a PSP rerelease of the original FF Tactics, and my memory tells me that many fans were overjoyed at the prospect of a widescreen, portable version with new jobs and content. Critically, it would also sport a fresh new localization, the product of Joseph Reeder (part of FFXII‘s localization team) and Tom Slattery (responsible for the GBA retranslation of FFVI, as well as the DS remake of FFIV). I myself was plenty excited at the prospect, but perhaps more due to the fixed errors than any high-minded thoughts of it being truer to the source material (that attitude comes later for me).

The game we got wasn’t perfect — in particular, a desync bug introduced slowdown where there was once none and led to audio and video glitches when using special abilities or items. That said, the new content was largely good, and the new script brought the quality of the game’s writing more in line with its lofty narrative aspirations. Some have criticized the new dialogue as overblown or faux-Shakespearean, and while I can understand those complaints, I’m not really in agreement with them. For me, The War of the Lions made me reconsider what writing in games could do for world-building and truly creating a sense of place. It drove me to revisit other seminal localizations like Vagrant Story and Final Fantasy XII with a new eye for what was occurring behind the scenes, and it fundamentally changed the way I consume writing in games.

I spent hours comparing the original English script to the revised version. The differences were shocking to me. I marveled at the liquidity of the two English texts, which I had once thought came from an immutable “source text,” whose meaning could be mathematically reduced to something concrete and then rendered into one Objectively Correct English. Much later in my life, a professor told me, “If you give ten translators the same source text, you’ll get ten completely different pieces of writing back.” Thinking back, War of the Lions was my first experience seeing this concept writ large, and it changed the course of my life. No longer was “the original Japanese” something monolithic and unchanging, it was something that could be poked and prodded and nudged endlessly in the pursuit of trying to recreate it in a new form, and that idea still captivates me today.

The Hokuten Knights, once merely just a cool-sounding cadre of knights, was now the far grander “Order of the Northern Sky.” The word isn’t changed: the 北天 (hokuten) in 北天騎士団 (kishidan, knights order) literally means “northern sky,” so it’s not like the original game’s rendering was incorrect. However, to an English speaker (perhaps an 11-year-old one who really loved FFVII last year), the word “hokuten” doesn’t mean anything, it just sounds cool. By contrast, this new localization’s attempt to create a more distinctive sense of place and to call to mind a specific tone meant that a romanized Japanese word had now expanded and gained more of the meaning it held in the original in the process. The Hokuten Knights had become the Order of the Northern Sky.

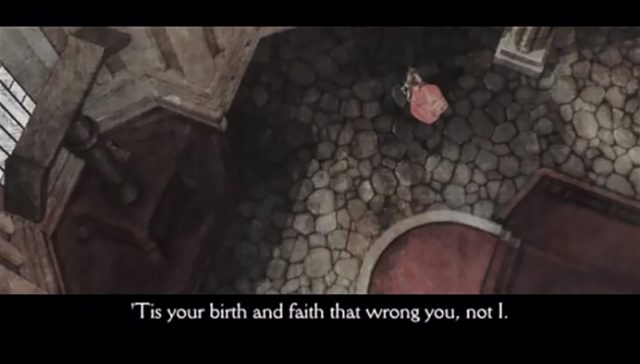

Another example that struck me: “Tough… Don’t blame us. Blame yourself, or God” became “Forgive me. ‘Tis your birth and faith that wrong you, not I.” You don’t need to speak a word of Japanese to understand that while similar things are being uttered here, there’s a difference in nuance that changes the tone of the speaker (Delita, when kidnapping Princess Ovelia). Now, in the original game, this line appears as Delita rides off on a chocobo, seemingly speaking to Agrias.

On the other hand, the War of the Lions version appears during one of its (beautiful) animated cutscenes, and makes clear that he actually seems to be speaking to Princess Ovelia.

In either case, the original Japanese line is 悪いな…。恨むなら自分か神様にしてくれ。 (Warui na… uramu nara jibun ka kamisama ni shite kure.) If I were to take a stab at directly (and roughly, so don’t email me demanding I be fired, please) translating this, it’d be something like “Sorry… If you must blame someone, make it yourself or god.” While the original seems to have missed the mark on warui, which is a word that means “bad” but can also be used as an apology or a way of saying “my bad,” the rest of it is still pretty technically correct. The real difference comes in how we choose to interpret Delita’s tone. Perhaps because the original English version went with “Tough,” the rest of the line takes on a more combative and callous vibe, whereas War of the Lions Delita seems more somber and resigned — this is the way of things, and it is the state of the church and society that forced his hand, not malice.

I could, and someday might, go on at great length: there’s a huge amount that can be learned from comparing re-translations of games (and literature and everything else), but I think my point is clear. The source text isn’t something that can be broken into component pieces in search of an objective “true translation” above all others, and this is true of any piece of writing or speech in any medium ever. The search for the meaning in any given piece of language is a practically philosophical endeavor, and if a video game had to introduce me to that notion, Final Fantasy Tactics is a pretty good one for it. Translators are also writers, and the number of solutions to any given question are practically infinite. War of the Lions was my first exposure to this idea, and for that, I’ll never forget it. Also, it’s a pretty rad game, too. I think I mentioned that somewhere.

For additional comparisons between the PS1 and PSP scripts, check out this excellent page. For the Japanese script, you can jump over here.

Finally, if you’re interested in reading someone far more able to talk about translation than me, I highly recommend taking a peek at Walter Benjamin’s “The Task of the Translator,” or perhaps Mathelinda Nabugodi’s outstanding analysis.