After 15 years in the making, Freehold Games’ Caves of Qud finally left Early Access in December 2024. After half a year of playing, I finally finished the campaign and feel qualified to review it. Many reviews I’ve seen of Caves of Qud begin similarly: the writer tells a fun anecdote particular to their playthrough. Such stories help highlight the game’s complex emergent and procedural systems, the breadth of gameplay possibilities it offers, and the variety of original experiences that can stem from that.

Caves of Qud is not the only game to captivate players in this way. Some obvious comparisons include titles like Kenshi, Noita, and of course Dwarf Fortress—games that a player might have barely scratched the surface of after fifty-plus hours of investment, but seem to become “Overwhelmingly Positive” (in Steam parlance) for those able to break past the enormous and intimidating tip of the iceberg.

I have a complex relationship with games like these. When I read anecdotes like the ones I mentioned, or see how people create full-fledged fiction based on Dwarf Fortress instances, I want nothing more than to experience that appeal for myself. Then I try the game. I get overwhelmed by the sheer number of immediate options, lose motivation from the lack of direction and necessary time commitment, or even struggle to figure out how to interact with the damn software. “Maybe I’m an idiot,” I think. But then I remind myself that not all games are for all people, and that it’s no sin not to gel with ones that require extensive research just to get started.

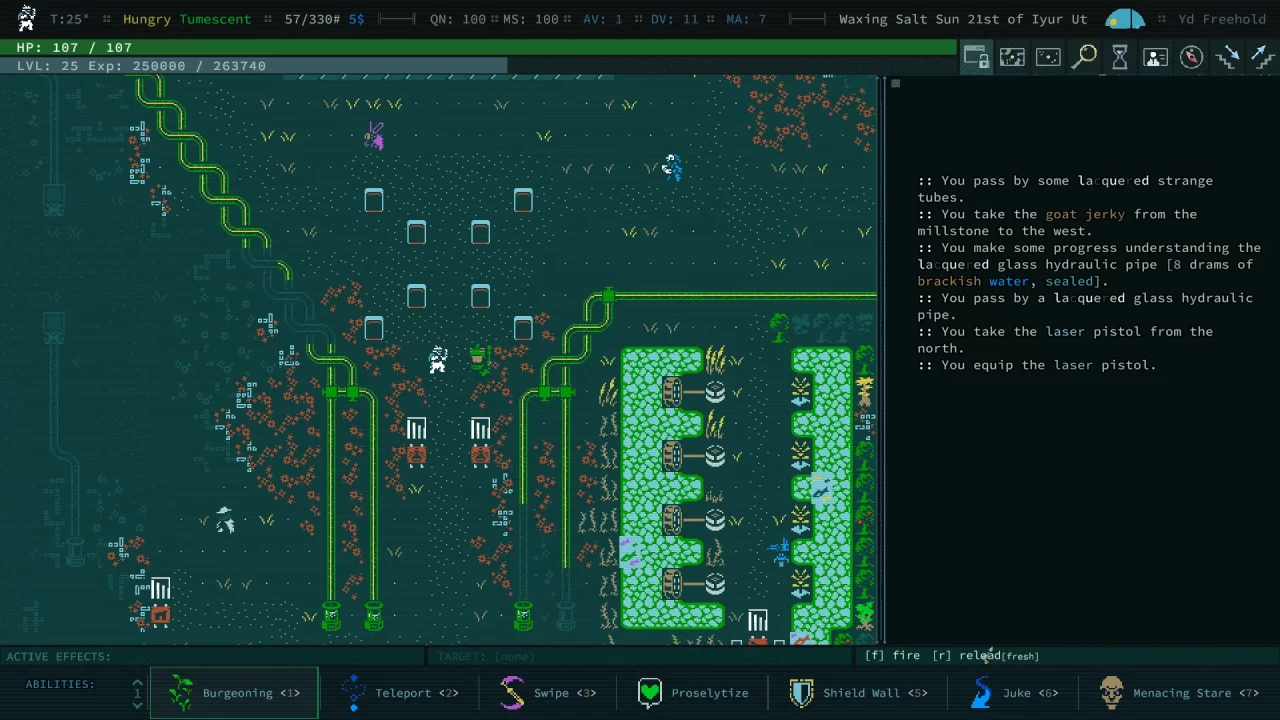

Word on the digital streets was that Caves of Qud is different. More accessible. Could be enjoyed simply as an RPG. I wanted to believe this, and I’m delighted to report that this is a (mostly) fair assessment. After getting used to the wacky control scheme—whether playing on keyboard or with the arguably superior(?!) gamepad controls—you can quickly get going on seeing what the richly imaginative yet apocalyptically hostile world of Qud has to offer. Like the original Ultima games, game objects move and react in tandem with your actions. You melee attack by bumping into enemies and can mix in skills or ranged attacks. The basics are simple enough. Thing is, you have a lot to learn beyond the basics, and you will do so by dying.

In its default setting, Caves of Qud is a roguelike. I imagine this is the default because the developers want players to treat death as a beautiful oops. For example, if you receive a message that an enemy on the screen has started “sundering your mind” and you do not immediately rush to kill it, your head will explode. Oops!

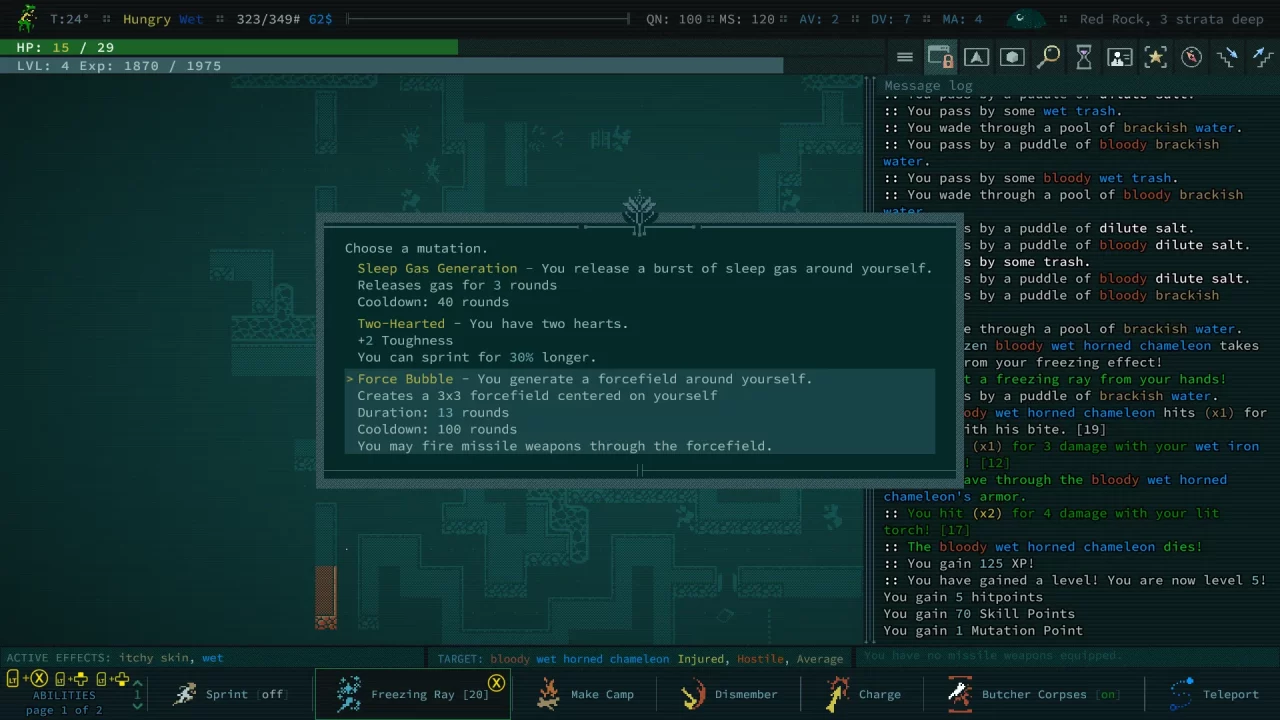

Death is a way to gain knowledge of Qud’s fascinating alien logic. It’s also an opportunity to try something new through the phenomenal character builder. In terms of vast and tangible variety, Caves of Qud is a contender for the best character-building I’ve seen. Beginners can try out the many thoughtfully crafted presets while veterans can get as weird as they want with it.

Alongside weapon specializations and the potential of non-weapon skills like Tinkering and Cooking, the key element of most character builds is their mutations. Mutations can involve anything from extra limbs (with equippable slots), status-inducing excretions, teleportation, mole-like digging claws, and about 70 other wildly creative perks. Say you want to play a gunslinger: how about one holding pistols in each of their four arms with the ability to unload full clips in tandem through a forcefield? Or an axe-wielder that shoots a freezing ray, rushes in for close-quarter combat, and starts savagely dismembering your enemy’s limbs? Every character I tried in Caves of Qud felt distinct and playable, although some builds were certainly easier to get started with than others.

You can get new mutations as you level, but RNG will decide the limited selections to prevent players from reusing the exact same busted build they discover every time. This also helps ensure every run and character you play with feels uniquely memorable. There’s also a second character type, True Kins, who have compelling lore and gameplay differences from Mutants. Instead of mutations, you build your True Kin by finding cybernetic implants that you can modify yourself with. It’s a cool, alternative playstyle, but I wouldn’t recommend starting with it.

I know there are RPG fans out there who get more out of frequently restarting a game with a new build over focusing on completing a campaign. Caves of Qud is built with them in mind. And yet, as someone who falls into the completion camp, I never felt like I was playing the wrong way by opting for the alternative Roleplaying mode. This setting is exactly what it sounds like: playing the game as a more conventional RPG.

Instead of starting anew when you die, in Roleplaying mode you end up back in the last settlement you visited. This helps immensely if you want to prioritize getting through the game’s difficult main questline. Yet there’s still enough punishment for death to make every step you take (“every move you make~”) a thrilling, involving affair. While the world of Qud features virtually endless explorable dungeons underlying its surface, each main quest features unique challenges that test your knowledge of the game’s logic and systems. The deaths you face when first confronting these challenges will sometimes feel cheap. However, persevering through them with creative workarounds provides a novel sense of reward.

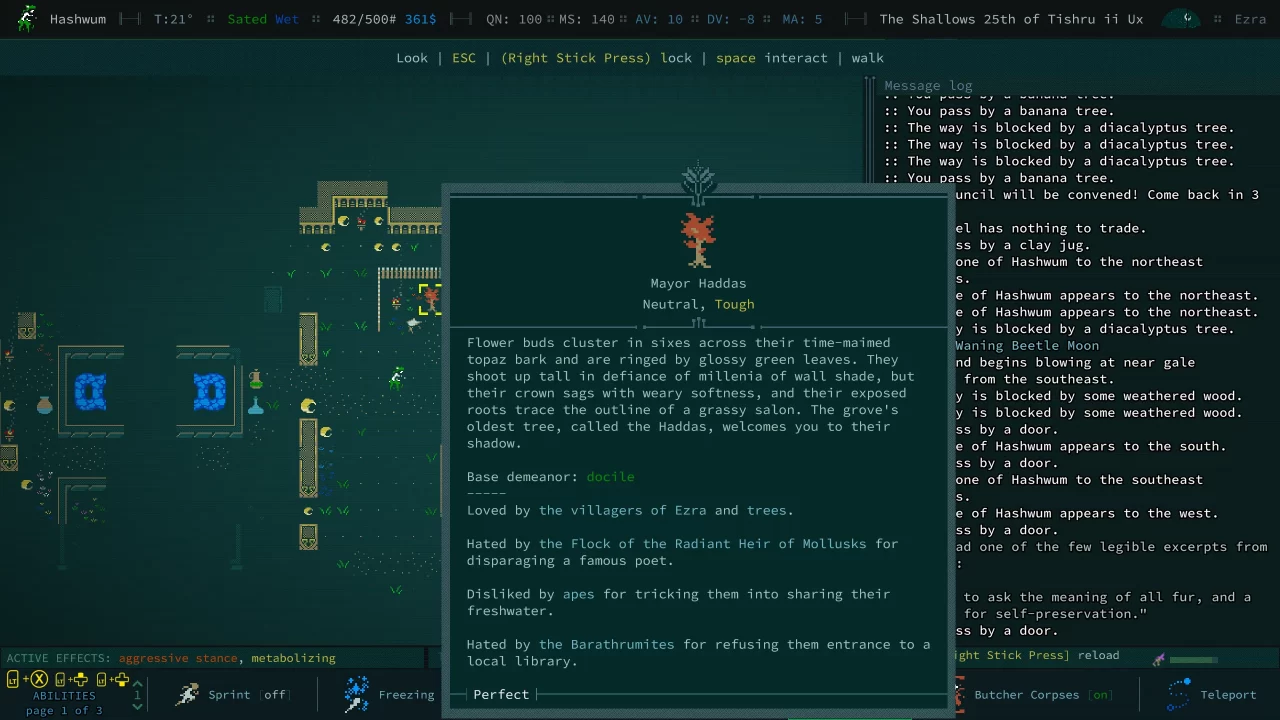

But Caves of Qud isn’t all about the creativity and variety of the gameplay. It won this year’s IGF award for Excellence in Narrative against some worthy nominees, and I can understand why. Behind the labyrinth of space, systems, and procedurality is a carefully crafted main story, set characters, and expansive lore. A salt-and-chrome-drenched world where rare fresh water is both a necessity for survival and the main currency. A world where species of humanoids, robots, plants, animals, and everything in between have their own sense of cultural identity and make up factions you can win the favor of or become despised by. It doesn’t feel quite like any fantasy or sci-fi world I’ve engaged with before, and that’s a remarkable achievement.

Visually, the world of Qud feels Ultima-like in its minimalist graphics, Night Mode aesthetics, and grid-based layout. Even with these graphical constraints, though, the atmosphere oozes character and arcane intrigue. It helps when the writing is so original and evocative. NPCs and lore texts will describe aspects of the world to you with word combinations that are based more on stimulating your imagination than logical exposition. And yet these descriptions don’t feel completely illogical either. There is tangible worldbuilding here, don’t get me wrong. It’s just based far more on vibes than the plainspoken (and often boring) writing you’ll find in so many other RPGs.

Another contributor to the dense atmosphere is the bonkers OST. It’s like the composer learned about music composition by listening to nothing but the original Fallout soundtrack on repeat until they spiritually transcended. The soundscapes range from the psychically violent to the anxiously serene. Alongside the writing, the OST does some heavy lifting in providing the world its aesthetic flair to compensate for the necessarily simple graphical style. I only wish there were more tracks, considering how much game is here.

These stable narrative elements join the developer’s innovative approach to proceduralizing history. Freehold Games invented code to modify the descriptive text of certain bits of the world of Qud’s history every playthrough. For example, there are always five sultans that are foundational figures in Qud’s past, but their names and historical achievements are malleable. Conflicting accounts can also exist across sources—lending an aura of historical mystery and authenticity. Each run therefore results in a new gameplay and narrative experience. This system leads to discovering evocative and amusing flavor text like, “The villagers of Damor laid offering at the feet of Batul, legendary feral dog, in exchange for wisdom about finding the ideal place for hissing under the Beetle Moon.” The developers have essentially executed the peak creative function of GenAI for videogame storytelling without even using GenAI.

Despite the degree of care that went into the main story progression, some unavoidable truths come to light when looking at the Steam achievements. Less than 20% of players completed the first main questline. The second main questline? Less than 10%. And less than 2% have earned the achievement for completing the game. Granted, much of the community likely got sidetracked having the kinds of experiences covered across the other 140 achievements—like “Wear your own severed face on your face,” or “Project your mind into a goat’s body.” Fair enough. But it highlights what is simultaneously the game’s greatest strength and weakness: there’s a lot to take in.

Of course, an essential part of the appeal here is that each player, and each playthrough, really will result in unique stories to tell. You don’t have to dig deep on the net to see a community full of fans excitedly narrating a unique, amusing, and/or tragic experience that Caves of Qud’s deep simulation allowed to happen. This procedural brilliance, combined with the lovingly vibes-based worldbuilding, leaves the door open for endless possibilities of emergent gameplay moments and narrative interpretation alike. Caves of Qud understands and confidently leverages the unique strengths of this medium towards its own ends.

As someone generally more motivated to complete a playthrough than get caught up in a cycle of experimenting and restarting, I’m not sure I’m the main audience for Caves of Qud. This makes me even more impressed by what a good time I had with it. Whether you’re signing up for one playthrough or one hundred, it’s hard not to be captivated by its depth and imagination once you get a sense of how the world works. And if I were the type of player who liked to invest the bulk of my gaming time in one single-player experience, this would be a rabbit hole worth falling into.