Media tends to exist in dialogue with the hauntings of our past. The ragged glories of long-forgotten yesteryears, the nostalgia we cling to for those we’d best move on from. Much of it posits a dire, cynical theory: the idea that, just maybe, we were doomed from the start. Perhaps The Pale grows ever closer, disappearing all in its wake with the subtlety of a whisper and the violence of a black hole. Within this inky rupture lies nothing but annihilation, an objective absence more crushing than the fathomless depths of the oceans. Darkness. The void. But where other works see fit to push us ever deeper into this chasm, Disco Elysium gives players the tools to pull its characters up from the pit and down from the aether. To get there, however, we have to start with nothing.

Disco Elysium opens with two disembodied speakers, The Ancient Reptilian Brain and The Limbic System. With voices like tar laced with arsenic, they taunt us on the foolishness of our continued existence. This is our introduction to the game’s dialogue choices, as the player is given agency to agree with these romantic salesmen of oblivion or disregard their honeyed overtures. But just as we’ve a mind to answer, we are awakened by the sound of a roaring 130-kilowatt engine. Our avatar stands up, dressed solely in yesterday’s white briefs and black socks from the day before that. Our motel room is trashed. The hangover is unbearable. He remembers nothing: total retrograde amnesia. Disco inferno, baby.

Just after this ignoble introduction, we learn a few key things about our character and the city he’s awoken to. This walking dumpster fire of a man is a cop from the 41st Precinct, and he’s here in Martinaise, in the disgraced former capitol of Revachol, to investigate a hanging in the back of the motel. We’ve been partnered up with the highly-professional, bomber jacket-wearing darling known as Kim Kitsuragi, a Lieutenant from the neighboring 57th Precinct. Disco Elysium is a role-playing experience. There’s no combat system to engage with and over one million possible words to comb through. And while this might be the most novelistic game I’ve ever played, I would never call it a novel. The aesthetics are essential, and the mechanics are the message.

The environment is presented in a painterly fashion, drawing on influences from artists such as Ilya Repin and Jenny Saville. The visual design is highly effective, as the grime of the buildings plays off of the exaggerated, stark faces of Martinaise’s many broken residents. Animation is limited but used judiciously enough to give a tangible sense of kinetics to this urban powderkeg. I would be remiss not to mention Anton Vill’s mesmerizing “Thought Cabinet” art, a marvel all its own in a game full of them. The score is composed almost entirely of licensed tracks from the great indie rock band British Sea Power and, had I not known a few of these tunes beforehand, I would have never guessed they weren’t composed specifically for the game. But whether bespoke or not, the audiovisual experience was, on the whole, masterful in its steadfast support of the game’s greatest narrative achievements.

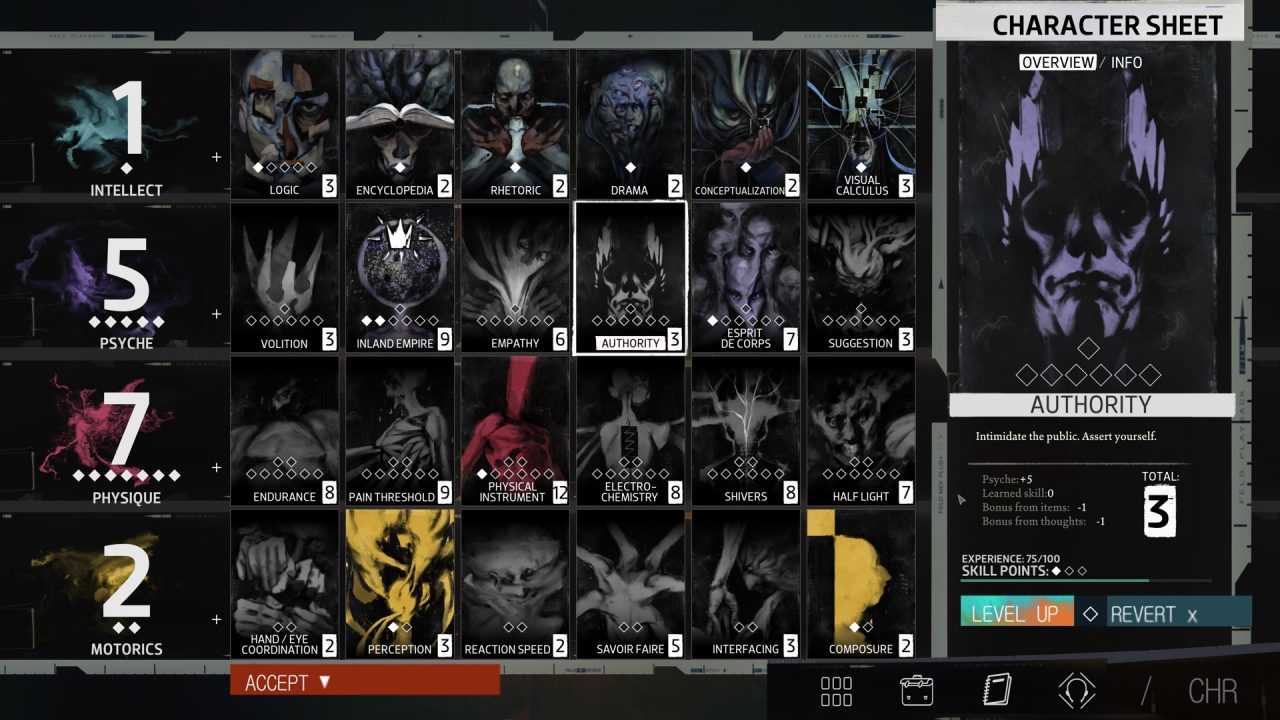

The story is largely direct and highly accessible, presented through some of the most varied and compelling writing present in the commercial space today. Frequent skill checks govern dialogue choices and actions, and there are 24 skills to pour precious experience points into. Some of these are rather self-explanatory (“Hand-Eye Coordination,” “Pain Threshold”) but others are far more obscure, and all of them have varying effects that twist into forms both hilarious and ingenious. I personally recommend leveling up skills such as Inland Empire, which increases sensitivity to “dreams in waking life,” and Esprit De Corps, which helps with the understanding of “cop culture.” Shivers may not be the most consistently needed for checks, but the skill is invaluable for understanding what makes Martinaise tick and sputter. Encyclopedia may grant historical context for Revachol, but get it too high and the driest skill in the book seems to forget the inherent joys of silence.

Along with the 24 skills, some of the highest praise I have for Disco Elysium has to be for the game’s signature mechanic, the aforementioned Thought Cabinet. If the player comes across an idea in this world, like ultra-liberalism, a confusing brand of racism, or even “Volumetric Shit Compressor,” they can choose whether to internalize the idea or allow it to stay untouched. It’s a fascinating concept and works surprisingly well in practice. By the end of the game, the Thought Cabinet had given me the ability to deeply understand Mazovian (Marxian) economics, apologize with much greater enthusiasm than is ever necessary, and even recover my own birthdate. The skills and thoughts intrude on conversations and physical interactions constantly, playing out like a twisted Greek chorus, and they’re brought to life in The Final Cut by first-time voice actor Lenval Brown.

Though I haven’t played the launch version, I can’t imagine this game existing without Brown’s melodious tones accentuating the entire affair. In fact, many of the denizens of Martinaise receive expanded and improved performances in this definitive offering. The hosts of popular lefty podcasts such as Chapo Trap House and Red Scare are now replaced by professional voice actors, and other sharp recasting decisions have allowed for a more consistent, higher quality experience. These characters metaphorically (and at one point quite literally) sing with outstanding clarity and nuance, bolstered by the additions found only within The Final Cut. The Final Cut is a free update for PC players who purchased Disco Elysium‘s acclaimed initial release in 2019 and marks the first time the game has appeared on consoles, with the PS4 and PS5 versions hitting digital shelves in late March and Xbox/Switch ports on the way later this year.

While this review mostly borders on the rapturous side of things, Disco Elysium isn’t always a blissful experience. The pacing of the narrative is uneven, and I did get to a point where the plot dragging and a string of failed checks left me spinning my tires for several hours in an attempt to discover how I could continue the main scenario. As with any interactive experience of this sort, I was occasionally presented with a set of dialogue choices that I didn’t find compelling or desirable. There’s a profuse amount of disgust presented to the player in Martinaise. Most of it is framed with great care and wit, but some comes across as undercooked and somewhat sloppy. I’m not particularly fond of how Latino-coded characters such as Call Me Mañana and Tiago are presented, though their more sensitive portrayals in The Final Cut go some way towards lightening my criticism.

Additionally, one character is portrayed as a type of “pixie dream girl” hounded by the main character in slumber and conscious existence. I’ve seen it before: some besuited disaster treats a woman poorly, they end their relationship, she moves on, he does not, he slips into self-destructive behaviors, harasses her in his worst moments, begins to move on and put his life back together, doesn’t receive specific accountability for his actions towards her, and walks off into the sunset. This is interrogated slightly at the end of the game, and I do think our main character is deserving of redemption, but I found the critique of his all-too-common romantic/sexual trappings to be lackluster in comparison to the rest of what Disco Elysium attempts to say.

By a wide margin, The Final Cut‘s most egregious flaw is the extremely unstable performance on console. Though the game often appeared quite stunning in 4K on my PS4 Pro, I experienced 12 hard crashes and two complete data corruptions, in addition to a veritable smörgåsbord of locomotion bugs and frame hitches. If I hadn’t recently subscribed to Playstation Plus in the event of issues such as this, the entirety of my saves would have been gone. I would have lost 35+ hours worth of progress instead of 1, and the gripping story that had been playing out from all my random dice rolls and experience allocations would have gone unresolved. The team at Studio ZA/UM have been working tirelessly to patch this version on Sony’s consoles, and I have full confidence in their ability to make the PS4/PS5 experience nearly as solid as it is on PC (hence why this criticism will be reflected under “Control” but not in the overall score, as it will likely be irrelevant within weeks). Pandemic or not, this port of Disco Elysium should not have been released in such an unreliable state, and having to rely on an external subscription service to continue a playthrough of the game could be considerably more than merely irksome for players without access to backup data.

Despite my occasional narrative discomforts and technical gripes, Disco Elysium: The Final Cut is absolutely essential material. This is a game that will stir the mind with masterful prose in one moment and have you gasping on the edge of your seat from the crucial roll of a cube in the very next. Disco Elysium will split your heart open with tectonic ferocity and leave you demanding more games exhibit the positively shameless amount of grace and humor that peppers every minute of this cerebral adventure.

From the most hemmed-in of interstices, the deepest of all swales, and the coldest, most ruinous morning of your life, you exist. You might awaken with bloodshot eyes, a headful of regret and a stomach filled with things far worse. But today… today is always the day you can begin again. We can be better, save each other from the crevices and darkened corners where we’ve kept ourselves hidden. It won’t be perfect; it won’t be pretty. In fact, it’ll probably be ugly as shit. You might kick and writhe, scrape and struggle until your nails bleed and your throat turns to sandpaper. But it’ll be right. And life will go on.

Hey. Look up. You’ve still got time.