Hashihime of the Old Book Town append is almost a novel, almost a visual novel, almost a kinetic novel. Yet despite all these “almosts,” Hashihime takes complete advantage of its medium to weave a spellbinding yarn layering the ugly with the beautiful, the messy with the clean, the empty with the full. Its tale of self-discovery and experimentation through fiction, the conflict between the author and their work, and the cycle of creative influence is mesmerizing the first time around and only gets more and more enthralling with each repeat read.

The story of Hashihime is told through words, images, sounds—judging this book by its cover leads one to think it’s a boys’ love visual novel. But playing through, players won’t find a single decision to be made. It’s actually a kinetic novel—but not quite, as there are clearly multiple love interests the story could follow. After completing the story once, exactly one choice is added to the narrative that, when chosen, steers players into the next route. With each completed route, a new story-splitting decision appears later into the “common” chapters until the entire tale has unfolded.

This unconventional approach between an involved, decision-filled visual novel and an entirely passive kinetic novel makes the most of what both mediums have to offer. The minimal choices contribute to the game’s “novel” feel, befitting its subject matter. The paths that branch out from different points across the narrative’s trunk deliver the story in a controlled manner that benefits its flow, gradually and consistently adding character revelations and building lore with each passing route. Each route accumulates into a seamless experience with the depth of a multi-route visual novel, yet without the unrestricted element of players experiencing routes in any order, thereby affecting their biases and understandings. The multi-route format also naturally fits the game’s BL undercurrents, giving each love interest his own route and focus.

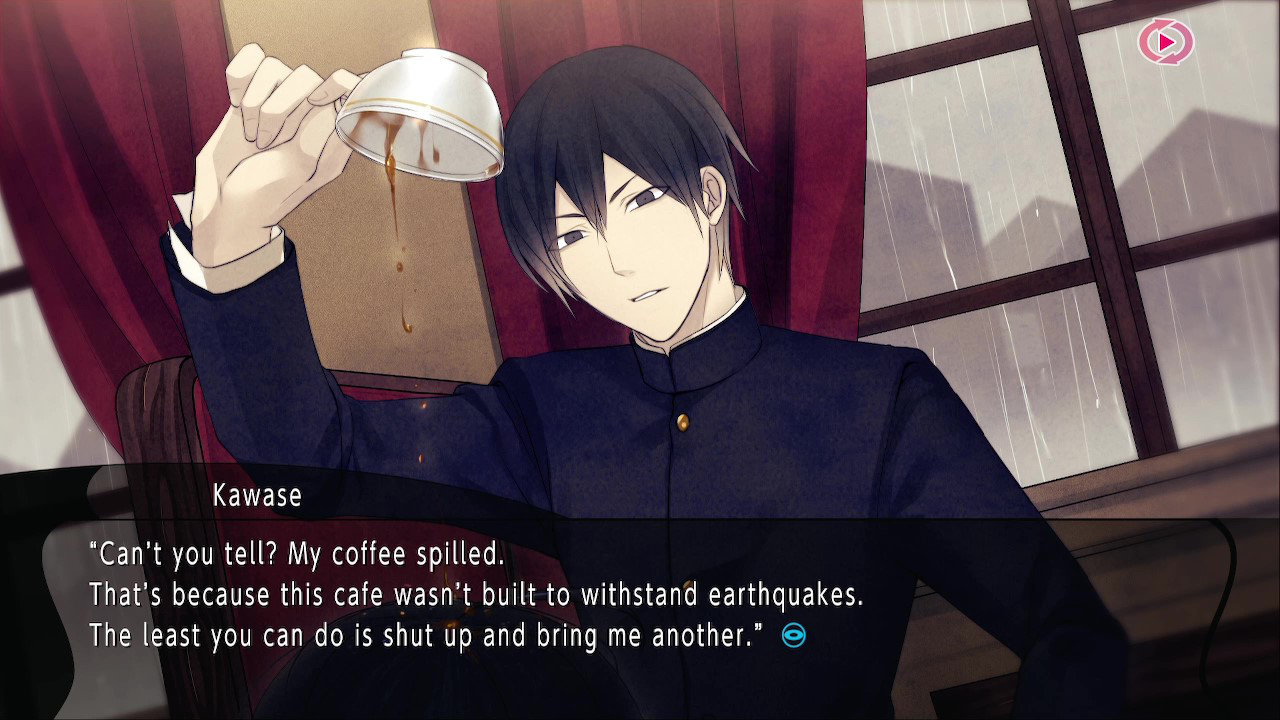

The target of the love interests’ affections is Tamamori, Hashihime‘s protagonist and an absolute disaster of an individual. This wannabe writer couldn’t get into the Imperial University like his childhood friends Minakami and Kawase, and lives meagerly in an unusual old bookstore, Umebachidou, only thanks to the good graces of the mysterious shopkeeper, whom Tamamori never even sees. What he does see, however, are “hallucinations:” his imagined characters and worlds that literally spring to life around him. Tamamori gets to interact with both his hallucinations and his actual surroundings, and by removing the usual choices found in a visual novel, he is made into less of a “self-insert” than typical romance game protagonists. Instead, he is a fully-realized, complex character, more important to the narrative than even his love interests, and perfect for leading the story into its contemplative, disquieting, and often painfully raw territory.

Tamamori doesn’t shy away from admitting his imperfections, be they unremarkable and harmless—“The number-one reason I never put anything away in my room was because I was going to use it again later. My pens, ink, and manuscript paper were all over the place because it was too much of a hassle to stuff them into a drawer just to pull them out again.”—or profoundly troubling—“I hated myself. That was why I couldn’t trust the people who loved me.” His tamer faults are the hooks that yank the reader into the darkest depths of his being, with no escape from his intense weaknesses. Even his fears are laid bare in ways that are as gut-wrenching as they are poetic, such as his response to the question, “Are you that afraid of being alone?” “I couldn’t help but be afraid. Loneliness was like water. Streams. Rivers. Oceans. …They stripped away the shore, split caverns, created solitary islands. Nothing other than water could do all that. …That’s why I hated the rain.”

Tamamori’s flaws and fears contribute to his humanity and relatability in ways that a mostly-blank self-insert protagonist is incapable of doing. Relating to another person is far more distinctive than relating to oneself. More traditional visual novels allow readers to disregard their own flaws by picking and choosing only the perfect parts of themselves to inject into that blank slate. In Hashihime, Tamamori’s relatability forces readers to confront their own imperfections, especially ones they may generally try to avoid. No matter how repulsed one may be by the reflection in the mirror, it’s just enough of a trainwreck that it’s impossible to look away. Any eyes that manage to stray are caught by the quirks of the love interests or the haunting nature of Tamamori’s circumstances. This setup lays the unshakable foundation over which Hashihime can build a story that intertwines the bizarre with the mundane, where the mundane has a range in intensity as drastic as the bizarre.

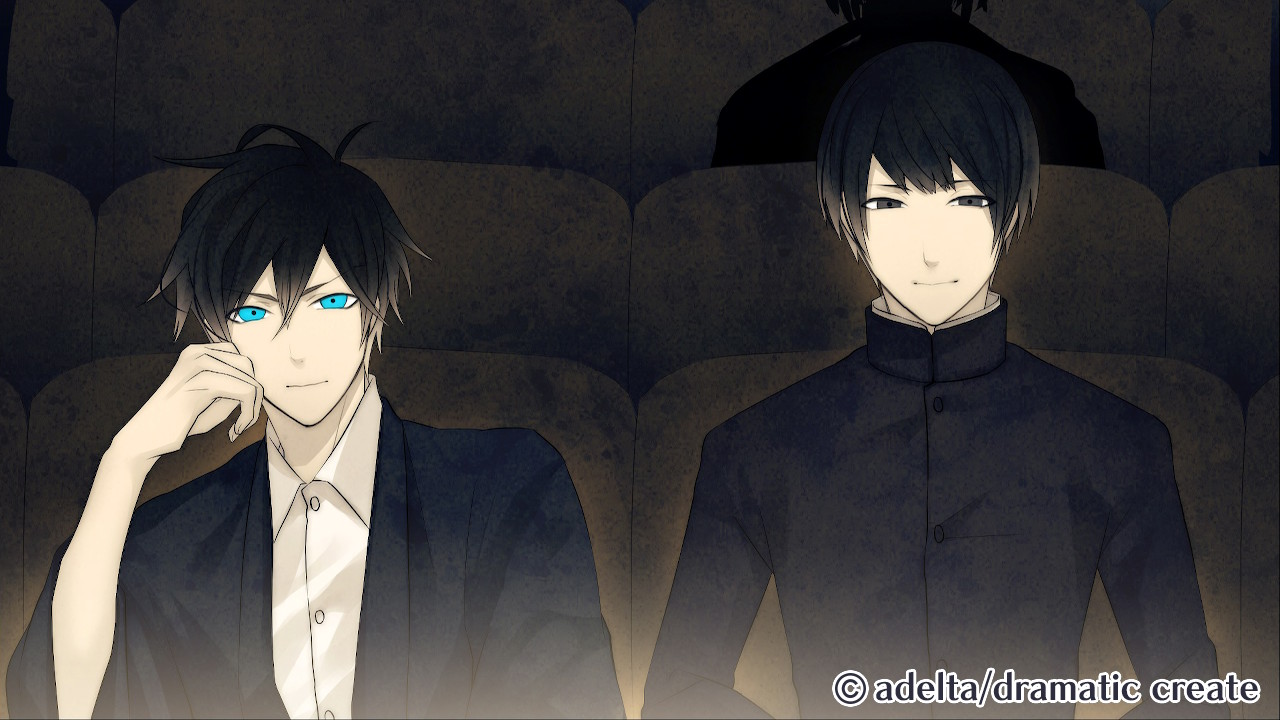

Hashihime’s intense disparities are further conveyed through a wide array of entrancing visuals. Dark, gloomy environments reflect the ceaseless rainy season and complement the attractive yet subdued character designs. These graphics representing the everyday are starkly contrasted with bright neon magentas and limes decorated with splotches, screen tones, and other ornamental patterns whenever Tamamori’s fantasies take shape. Other points of emphasis, such as Tamamori’s blue eyes and depictions of blood, also utilize bright neon tones to act as a point of consistency, threading together the real and the fantasy settings. Fantasy and reality further converge as Tamamori’s stylized characters pop in and out of scenes, including a heavily stylized author character named Haruhiko and a talking frog simply called “the Frog Man.” All these gorgeous juxtapositions—the bright beside the dull, the properly proportioned beside the cartoony, the realistic beside the surreal—remain firmly grounded by a subtle aged paper texture that envelops everything in a vintage wrapping befitting the Taisho era setting.

While Hashihime works to combine the novel with the visual-kinetic novel, it takes a rather unorthodox visual shortcut: characters often don’t have portraits shown when they’re speaking. In other visual novels, a limited number of character portraits can be a hindrance, such as when someone is described as having tears streaming down their face but their portrait doesn’t reflect that. This can be confusing as the reader’s eyes receive information contradictory to the writing. Hashihime‘s dialogue and descriptions are written in a very novel-like way, allowing readers to clearly visualize the characters as they are meant to appear even without the use of portraits. This is also assisted by countless backgrounds portraying each location the characters visit, and there are 177 immersive, gorgeous CGs in the main story routes for key scenes, with 47 more in the bonus chapters. Still, the lack of portraits becomes apparent when skipping already-read text to get to the next route or when perusing saved screenshots of favorite lines. It feels like the portraits, which emit a simple yet stylish charm, could have been used a little more without hampering the writing.

Whether supplemented by character portraits or not, the writing is always very eloquent, although marred by typos more often than is desirable. These can be easily overlooked, as Hashihime utterly absorbs the reader in its world. The nuances of Tamamori’s love interests, from Kawase’s dreadful attitude to Professor’s peculiar obsessions, cement each one as decidedly unforgettable, and paying witness to their growth alongside Tamamori’s is immensely satisfying. The characters are further brought to life through fantastic voice work. While fully voiced dialogue is par for the course in visual or kinetic novels, the voiceovers in Hashihime are particularly expressive to the point where it comes as a shock to see how few other works members of this voice cast have appeared in. Each character’s voice feels distinctly tuned to their unique manner of speaking and behaving, with Seiichiro Konno’s slew of outbursts as Professor being a marked highlight among an especially shining cast.

Another benefit of Hashihime‘s realization as a kinetic-visual novel rather than simply a book is its striking soundtrack. The game’s impressive breadth of songs adds to the bewitching vintage atmosphere by using period-appropriate instruments with tinges of psychedelic flair as needed. The melancholy strings and harpsichord of “Freezing Goldfish” have a hint of eccentricity that perfectly encapsulates the feel of Professor’s character, while the bumbling brass of “The Imperial University Student’s Narrative” moves from awkward to hopeful in an unquestioningly fitting theme for scenes pertaining to the three halves of a whole idiot group of Tamamori, Minakami, and Kawase. When in Tamamori’s most spirited hallucinations, “Fantasy of the Southern Sea” chimes in with bells and other percussion instruments to create a dizzying, otherworldly tune; when back in reality, the jazzy slap bass, guitar, and piano of “Dreamy Old Book Store” firmly grounds its written and visual surroundings in a sense of complacency and comfort.

Hashihime’s ability to seamlessly move from comforting to discomforting—the real to the illusory, the silly to the serious, the average flaws to the critical—is as fluid as a river. It never shies away from the ugly, but that only makes its pristine moments shine all the more beautifully. Hashihime’s subjects and characters challenge readers by not being perfect, by being downright despicable at times, by acting as mirrors. At first glance, they seem to be funhouse mirrors, but upon closer inspection, it becomes clear that those reflections are the real deal. Locking eyes, it becomes impossible to look away, and Hashihime beckons to be experienced again. No matter how many times you dive back into those biting waters, Hashihime of the Old Book Town append leaves its chilling impact.