In his preface to the 1995 Prima Strategy Guide to I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream, then-62-year-old sci-fi author Harlan Ellison addressed why he helped design a video game when he “reviles” games and computers at large. Characteristically, his first response was, and I quote, “Yo’ Momma!” He then elaborated by admitting that he had wanted to challenge himself in a new medium, even if he would never sit down to play it.

After the MS-DOS and Mac versions of I Have No Mouth released in 1995 (mere weeks before I was, erm, released to the world), the game was largely MIA until a PC re-release in 2013. As of March 2025, it has finally been ported to consoles thanks to publisher Nightdive Studios, and I was eager to get my hands on it, considering for decades I had no mouse, and I must play. Almost thirty years later, I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream is a bloody gem of ’90s point-and-click adventure games coagulated with the dated mechanics of its genre and propelled by the morbid curiosity surrounding its premise and reputation.

I was a fan of Ellison’s short stories as a teenager. They were edgy, envelope-pushing, and as abrasive as the man himself. Arguably Ellison’s most widely known story, 1967’s I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream is a brief account of five humans spared in the aftermath of the extinction of humanity at the hands of a malevolent, sentient supercomputer, AM, as in “I think, therefore I AM.” AM keeps the five humans as his playthings to continually taunt and torture for 109 years come the story’s opening, and ushers them like a dark god through what may or may not be a simulation, given how powerful the machine is and how surreal his world has become. The story ends… very badly, and thus it was perfect fodder for an edgelord teenaged boy’s reading. With the original vision of the game adaptation of the story, Ellison didn’t want there to be a win-state—he wanted to upset players and put them on “a playing field on which human emotions and human strength and frailties would matter.” Considering its story and atmosphere, the game is a blast to watch, read, and think about, while its gameplay certainly can be upsetting.

To start with, this re-release contains minimal new features, including a cheesy and rather unnecessary main menu, a playable soundtrack (including plenty of bonus tracks), and the ability to change the aspect ratio and pixelation of the game. Otherwise, the game’s choppy animations remain. I played on PS5 and within minutes I grew as accustomed as possible to the controls—typical verbs like “Look,” “Talk to,” “Use,” “Give,” and… “Swallow(?)” are mapped to the face buttons and triggers. The left analog controls the cursor and can click the action buttons, and thankfully, the directional pad can move the same cursor more slowly for finer clicks, like pulling on a rope. A text bar above your action buttons will highlight what you can interact with as you hover over things, so, as is common in the genre, you may find yourself slowly scanning rooms for interactables and trying every action you can with them, in which case you can expect to hear plenty of the five separate protagonists’ canned phrase equivalents of “I don’t know what good that’ll do me.” And oh boy did they record a lot of lines.

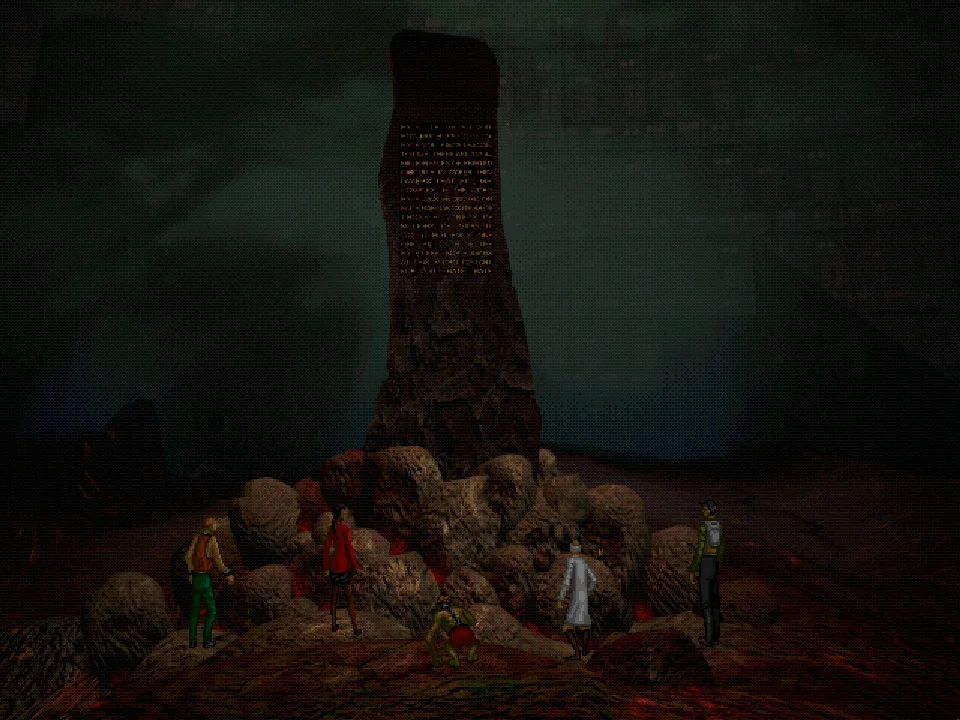

The game opens with Harlan Ellison himself voicing the omnipotent machine, AM, as he gathers his five human victims beneath the hellish, monolithic “Hate Pillar,” inscribed on which is his iconic monologue, lifted from the short story, about how much he hates humanity. Unlike the original story, AM extends personalized games to each of the humans as a respite from their tortured existences and a potential escape, setting up the five episodes that make up the bulk of the game. Ellison’s taunting and unhinged voicework as AM is a standout, and the writing is, as expected, leagues beyond much of what was in players’ hands at the time. Having read the story many times in my youth (and rereading it before playing this game), I never considered the manic humanity within AM, but Ellison brings it out with a twisted joy akin to Mark Hamill’s Joker performance. Each of the five humans—Gorrister, Ellen, Benny, Nimdok, and Ted—also have more distinct and fleshed-out personalities and backstories than their original incarnations, and their being selected for an eternity of torment is a little more understandable when each of their respective “psychodramas” is played.

Gorrister’s episode takes place in a corroded zeppelin and deals with themes of grief and self-forgiveness, a challenge the gruff trucker must overcome. The plot and the puzzles become increasingly dreamlike, and the hour-or-so-long episode has one of the more satisfying arcs, albeit with some of the most frustrating doors to click-click-click search for when navigating the environment.

Ellen’s episode whisks players to a tech-scrap Egyptian pyramid fitting of the engineer herself, including her pervasive and debilitating fear of the color yellow. Ellen is the most likable and innocent of the cast. However, her voice acting is inconsistent in tone, with her odd wisecracking essentially sapping a certain elevator scene of its rightful place as one of the game’s strongest (and most daring) moments. This leads to my complaint that’s not quite a complaint: the game is rarely as dark in its execution as it is on paper, and half the characters never act like they’ve been trapped in a Bosch-like hell for over a century. I Have No Mouth could never be called uplifting, but its retro sci-fi goofiness is present, with the drama and horror sharing less in common with Ellison’s literary output and more in common with some daring episodes of Star Trek or, especially, The Twilight Zone, both series Ellison had a hand in.

No section shows Ellison’s strengths and weaknesses more than Benny’s; AM’s “favorite torture toy” has been malformed over decades into more ape than man. AM restores his cognition before sending him into a tech-infused jungle village with the goal of cannibalizing the villagers. Benny’s appearance and backstory (not to mention his promotional material too disturbing to be included in the final game) are horrific, but his psychodrama plays out like a slow-paced, buggy buildup to a ripoff of Shirley Jackson’s The Lottery, with the increasingly unsympathetic World War III soldier Benny having to overcome his selfish hunger and learn compassion. Design-wise, this level is easy to soft-lock your progress on, and the steps to trigger progression events are very obscure. If possible, seek out online hints for the game’s puzzles rather than an outright guide.

Although Ted is the narrator of the original story, in this game, he is an uninteresting yuppy whose only discernible traits are that he loves his dreamlike version of Ellen and didn’t treat past girlfriends well. His level, though, is a fun setting: an old dark castle on a stormy night rife with demonic rituals and shifty servants.

Lastly, there’s Nimdok, the Nazi scientist, whose episode was removed entirely in past releases in Germany and some other European countries. Nimdok, given the task to “find the Lost Tribe,” is returned to a concentration camp where he is due for experimental surgery on Jewish victims—thankfully, as with Benny, trying to do anything reprehensible results in a game over and a return to the Hate Pillar. Visually, there’s an interesting slant to everything a la German Expressionist films like The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, and Nimdok is appropriately thrashed about, all the way up until his twist finale, which could be seen coming a mile away by even an amorphous jelly thing with white foggy holes for eyes.

If you meet certain conditions throughout the five episodes, the character’s portraits—or “spiritual barometers”—will brighten from black, to green, to white. Functionally, these serve as health meters for the endgame, though that seems to matter little as Nimdok is the only character able to progress past the endgame’s first “puzzle.” This is where the game fell apart for me. For three decades, certain countries that had Nimdok censored out of the game were locked out from the one of many samey endings that could be considered “hopeful.” Let’s just say that players who want said ending should brush up on their Jungian analytical psychology, as it involves confronting AM’s Id, Ego, and Superego. Like a lot of the game, that sounds very cool, doesn’t it? How it plays out, though, is not all that satisfying, and at times felt more like a high-stakes guessing game, where the stakes are the six to eight hours you’ve put into the game. Sure, you can always save scum, but having to rely on that to conquer puzzles is no fun.

Aesthetically, I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream has aged well. Its levels and their painterly backgrounds are artistically diverse and keep the game feeling fresh, and this is only enhanced the more hellish and surreal it becomes. Its uglier aspects, like its character portraits, further strengthen the horror vibes. The soundtrack, the one-time VGM outing for film composer and frequent Bryan Singer-collaborator John Ottman, is at times creepy, but mostly spooky fun to the point where my wife, not a gamer, came into the room and asked if the music was from Disney’s Haunted Mansion ride. The sound effects seem ripped straight out of Doom (1993), though the slight delay in their timing can be either off-putting or nostalgic based on the player. If, atmospherically, this game has survived for three decades, I Have No Mouth‘s strengths and intrigue will likely continue with future generations.

I’m glad I finally played I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream. Its concept very easily draws players in, and to an extent, I even enjoyed banging my head against its opaque puzzles, knowing that each subsequent episodic level would bring a refreshing protagonist and style. Besides an underwhelming finale and some questionable puzzle design, the game is not as misanthropic or depressing as it would seem. Instead, it will always be narratively remarkable as the sole video game in Harlan Ellison’s expansive body of stories, scripts, comics, and teleplays. Ellison passed away in 2018 at the age of 84 but may his morbid and gleeful performance as AM live on for at least another hundred and nine years.