I don’t like to compare video games. I prefer to evaluate each game on its own merits, as its own experience. I enjoy games much more when I do this because I don’t get wrapped up in what I think a game should be—it simply is. It’s very demure, very mindful, or whatever the hell kids are saying these days.

However, some games are so like their inspirations that it’s nearly impossible not to compare them. That brings me to the Turbografx-16’s Neutopia, Hudson Soft’s answer to the NES’ The Legend of Zelda. Considering how litigious Nintendo seems, I’m surprised they didn’t end up owning Hudson Soft and its cute little bee mascot. Since Konami does next to nothing with Hudson Soft’s extensive library of IPs, this might have been for the best.

And while there are many Zelda-likes now, I can still think of none more blatantly obvious than Neutopia. And to be clear, I enjoy Zelda-likes! There’s a reason so many developers have copied Zelda’s formula over the years, and more old-school Zelda is always a boon for me, especially since I’m not a fan of Link’s open-world adventures. So, I was immediately on board for a Hudson Soft Zelda, especially given their creativity and output during this era.

The world of Neutopia is ruled by the wise and beautiful Princess Aurora, who uses the power of eight medallions to ensure peace and prosperity throughout the land. Aurora and her ostensibly powerful medallions reside in a temple, and, wouldn’t you know it, the evil Dirth shows up one night and takes them all. Seriously, he warps to the temple, walks in, takes everything, and warps away. Apparently, Neutopia was having a going-out-of-business sale on royalty and mythical artifacts, and Dirth showed up right on time.

Look, Zelda isn’t winning any awards for wielding her powers or the legendary Triforce, either, but at least she has some guards, OK?

Anyway, because Neutopia is The Legend of Zelda, we need a hero. That hero is the courageous Jazeta, who, sword in hand, sets out to find the eight medallions in eight dungeons, rescue the princess, and save Neutopia from the world’s smartest shopper. Cheesy comments aside, it’s all quite familiar, yes? And in terms of gameplay, if you’ve played any pre-BotW/TotK Zelda, you know how it plays and what to expect.

Perhaps surprisingly, Neutopia improves Zelda’s formula in some ways despite nearing copyright infringement. First, the compass you get at the start points you toward a dungeon on the overworld. Once inside a dungeon, it points you toward the boss. It’s a fantastic addition because you can’t get lost when either is your destination. Second, the fire rod! It initially shoots weak fireballs, but as you increase your max HP, it eventually shoots fire pillars. However, its form and damage rely on your current health, so it reverts to garbage as you get injured. Fully powered, though, it is arguably more useful than your sword if only because you don’t have to get so close to enemies.

However, aside from the fire rod, Neutopia doesn’t even try to innovate with its items. You’ve got bombs, a healing potion, and a lantern and ladder that aren’t exactly those things but function like those things. Teleport wings are nice but perfunctory: they warp you back to your last save point. The ring, which replaces all the on-screen enemies with an easier version of that enemy, can be helpful, but you can only hold one item at a time, so you can’t strategize with it. The sword, shield, and armor upgrades do what they say on the label, nothing more.

While The Legend of Zelda is mostly nonlinear (for better and worse), Neutopia is more restricted. Its world is divided into four spheres, and retrieving the two medallions hidden in a sphere unlocks the next sphere. If you think “sphere” is an interesting way to describe the area in which you live, I agree. I had no idea what people were talking about when they mentioned spheres, and the laughable translation sees people mixing up “sphere” and “labyrinth” (I assume for “dungeon”) constantly. One helpful guy told me that another helpful guy lived near a fountain and had a valuable item for me! I struggled to find him because there are no fountains. Oh, he meant a waterfall. Whoops!

The Legend of Zelda‘s translation wasn’t great either, but a key difference here is that it only has a handful or two of people to whom you can talk. Neutopia is FULL of people, and they ALL want to talk to you! They either offer banal platitudes or give you advice, which, as noted above, is sometimes unhelpful. I’d say don’t bother talking to anyone, but then you’d miss out on shops, upgrades, and important items you need to play the game, so.

While Neutopia’s lack of identity, disappointing items, and 80s-style translation issues aren’t enough to ruin the game, two design choices nearly finish it.

First, Jazeta’s hitbox is his entire sprite, but the same isn’t true of his enemies, and the collision detection is unforgiving, resulting in constant hits, which can feel unfair. Enemies don’t seem to have any definable movement pattern either. They’re free spirits, and their fast, erratic movements send them everywhere. Sometimes, they bum-rush you; other times, they don’t seem to know you exist. It’s not at all uncommon for one to occur after the other. Also expect to get hit the second you enter a screen. The more I played, the more I dreaded encounters with common enemies.

This is why the fire rod is so much better than the sword, but even it isn’t a perfect solution. Fire pillars are solid damage dealers but move slowly as they cross the screen. As a result, fast, flying, and jumping enemies are a nightmare to hit. As your fire rod weakens, enemy projectiles also interrupt your shots. These issues make combat finicky and far more frustrating than it should be.

Second, and somehow worse, is the designers’ affinity for bombs. Like in Zelda, you use bombs to destroy walls, and just like its inspiration, there’s no way to tell which walls are fake. As a result, you make educated guesses (for example, the wall on the screen’s edge is probably real) and check almost every…single…wall.

Now, you’re probably wondering: how many bombable walls are there? I pulled up a map on GameFAQs and counted all the walls in the Sea Sphere’s overworld (world three of four) just for you, dear reader. There are 58. You can hold a maximum of 20 bombs, assuming you find all the upgrades, but that sometimes requires using bombs to find them. Oh, and some of the walls you destroy reseal after you leave the screen, including the shops where you buy bombs. And enemies rarely—if ever—drop bombs, so you’re stuck constantly buying more bombs if you can remember where the bomb shops are located.

To be clear, it’s not like you’re going to bomb all 58 walls in the Sea Sphere—unless you’re really unlucky. There’s only one fake wall in each section, but given that there’s no way to tell what’s real and what’s fake, it still takes an unnecessary amount of time and bombs to find everything. Look at sections A3–A5 in the map I linked above: there are 11 bombable walls, and none are fake.

I’m not ashamed of this, but I’ll be honest: I used GameFAQs maps to identify the right walls once I reached the Sea Sphere. The constant need to bomb every wall and then refill on bombs to bomb more walls is a chore. It ruins Neutopia’s pacing and sucks the fun out of exploration, which is a key element of its inspiration. And it’s even in the dungeons!

Neutopia’s dungeons are like The Legend of Zelda’s but more unfriendly. Finding a crystal ball displays a predefined area of the dungeon map but doesn’t include rooms you must bomb to access. Bombable rooms are removed from your map if you leave the dungeon. And important items—equipment upgrades, the key to the boss’s room, etc.—are often found in those areas. So, much like the overworld, you spend a lot of time bombing walls and praying you picked the right one.

What happens if you run out of bombs in a dungeon? If you leave to buy more bombs, the walls you destroyed will reseal. I can’t emphasize enough how infrequently enemies drop them, either. You either get lucky, or you’re stuck in a bomb-buying cycle. Even drawing your own map (for dungeons or the overworld) won’t save you from this trial-and-error design.

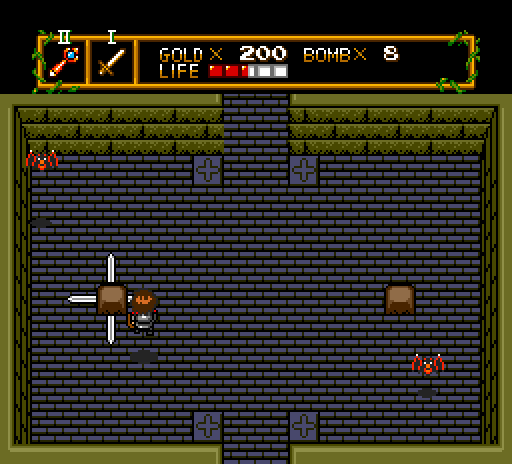

Speaking of hostile designs, you know how, in Zelda, you often must push blocks to open doors? Neutopia does that, too, but it likes to hide swords in blocks, and you won’t know that block is boobytrapped until you get stabbed. And since Neutopia has way more room layouts than Zelda, get ready to be stabbed a ton looking for the right block. The screenshot below illustrates how close you must get to trigger it. Can you do that for every block you think you can push? You don’t have a choice, and don’t forget—taking damage weakens your fire rod! It’s like the designers threw salt in your wounds, then pushed you into a vat of lemon juice.

While Neutopia’s enemy designs run the expected gamut of slimes to soldiers, its bosses are large and fierce, putting Zelda’s to shame. Some are reminiscent of the bosses Adol fights in Ys I & II. If you’ve played those games, you’re familiar with the same pain points: the bosses occupy a ton of real estate, constantly fire projectiles, and only show their weak point for about half a second. While they can be frustrating, they are satisfying to take down, much more so than, for example, a lethargic Gleeok.

Neutopia’s graphics are bright and crisp but a bit basic. Regardless of which sphere you’re in, there’s a lot of brick and rock everywhere. They’re still more inviting than Zelda’s dull landscapes, but not by much. Impressively, there’s little to no slowdown or flickering, regardless of what’s happening on screen. However, Neutopia’s soundtrack is full of bangers. I frequently listen to video game mixes while working and immediately recognize when a song from Neutopia starts. The Sky Sphere’s song almost feels like it could be in a shmup. It’s energetic, gets my blood pumping, and I love it. It makes me feel like I’m about to embark on an incredible journey with dire consequences for failure. I do wish they were longer and there were more of them, though.

While I appreciate that Hudson Soft tried to put its own spin on the Zelda formula, the result is unfortunate. Neutopia isn’t disappointing because it’s not Zelda: it’s disappointing because it doesn’t nail the basics, and its clumsy attempts to break from its inspiration derail what could have been a predictable—but solid—adventure. Considering Neutopia’s inspiration and its developer’s pedigree, I expected better. Here’s hoping the sequel, which I plan to review soon, is better.