Panzer Dragoon Saga is gaming’s most well-hidden masterpiece. And while it is not necessarily cloaked in underground obscurity nor buried under obtuse design, playing it legitimately today requires a monetary devotion that is practically unachievable for all but the extremely wealthy, making it a rare game to witness, even for die-hard RPG fans.

Additionally, those who already own Panzer Dragoon Saga hardly play their physical game discs to avoid loss-inducing scratches. Most collectors store their copies in cases in dark places rather than on nice, well-lit, public-facing shelves, and some even opt for collectibles or jewelry insurance for the game. I will readily admit that a poor grad student such as myself cannot afford a legal copy of PDS, though I’d play it if I did, collectors’ value be damned. In any case, just like anyone else who wants to play the game today — even most of those who legally own it — I must emulate it extralegally (SEGA, totally feel free to send me a posthumous review copy, by the way). Thankfully, SEGA has little history of litigating against emulators and their users; they even distributed raw ROM files in their SEGA Mega Drive and Genesis Classics collection on Steam. Still, the illegitimacy of extralegal emulated play requires devoting significant time, as fans must rely on hacks, guides, and forums to consume this rad RPG, and even then, it is a chore.

This situation is a bonafide Greek tragedy, because Panzer Dragoon Saga is the Titan Atlas cradling the world of modern videogame storytelling on its shoulders. It blends gameplay and narrative in a way that the gaming industry wouldn’t catch up to for nearly a decade. And it does so alongside a timeless story of eco-resilience, charming and tragic characters, a mysterious well-crafted world, and cutting-edge RPG mechanics.

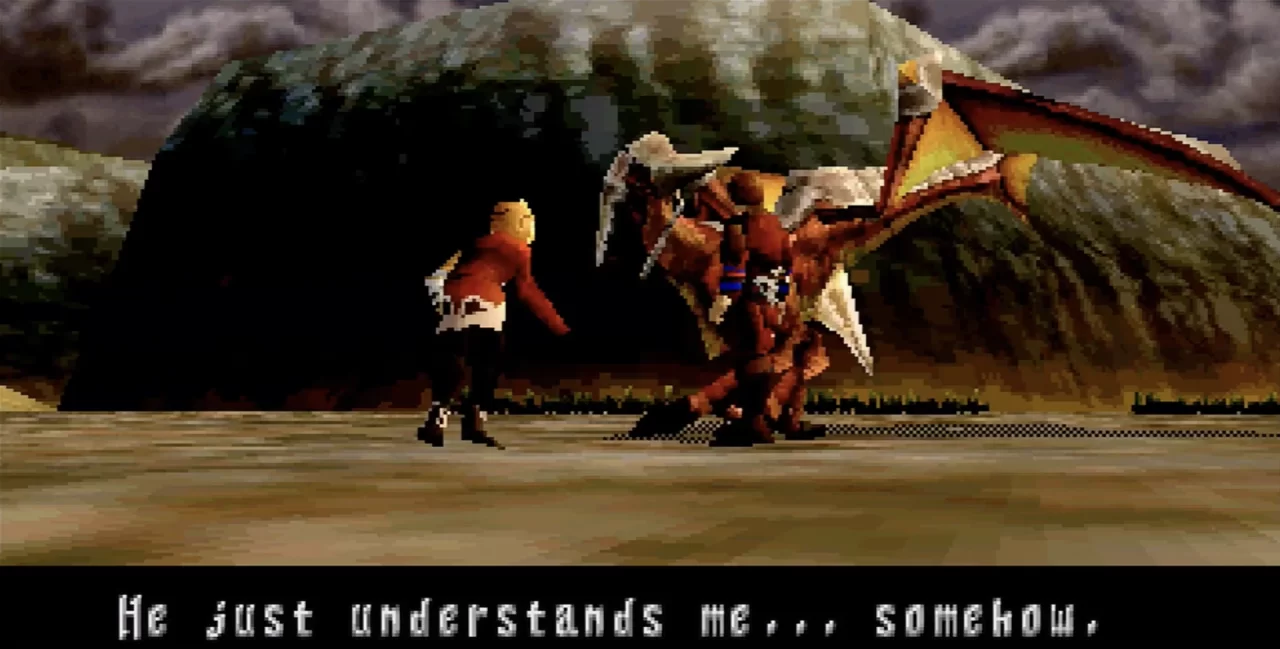

Panzer Dragoon Saga begins with Edge, a mercenary for the game’s oppressive, unnamed Empire, guarding an excavation site filled with technology from the Ancient Age. This technology is key to the Empire’s conquest to recolonize the world and return humanity to its ancient Anthropocene. Inside the dig site, Edge’s companions discover what appears to be Phoebe Bridgers encased in carbonite (see picture below) protected by a cyborg praying mantis creature, which Edge fights off with a rocket launcher. The scene becomes one of catastrophe when the Black Fleet, a fleet of former Empire airships led by a man called Craymen, descends on the site, kills everybody, and steals the girl. As the Black Fleet departs, Craymen’s feral right-hand man shoots Edge off a cliff, though a dragon quickly saves him and imparts him with the psychic memories of Panzer Dragoon’s past, present, and future dragons. Edge vows to get revenge on Craymen, who he now knows is headed toward a black tower.

Black towers feature prominently across the Panzer Dragoon series, and each game features a silent dragon savior imparting psychic visions about the towers on its rider. These elements are critical to the series’ plot, as the player must fight aggressive local fauna guarding the towers to eliminate the Empire forces who threaten to use them, and only the dragons appear to be keen on the mysterious towers’ purposes. Each game shares an ending where the dragon leaves the player behind to destroy their respective black towers.

In Panzer Dragoon Saga, the player learns about these stories through its own early dragon vision and in-game books, which can be discovered or purchased throughout the game. They tell stories about the Empire, the Ancient Age, and the Divine Visitor, a prophesied entity who may bring an end to the destructive Ancient Age technology that keeps the world in a cycle of warfare, commercialism, and environmental destruction. Edge posits that the dragon is this Divine Visitor, and he seeks to aid the dragon in its quest, as long as he can get the revenge he desires against Craymen.

Throughout the game, the player navigates through airborne zones, fighting randomly encountered enemies and setpiece-driven bosses; occasionally, the player can visit campsites and towns on foot for shopping and character development beats (and, again, the occasional lore tidbit). Combat combines the series’ famous multi-angle shooting and active-time turn-based battles. Players can choose between magic abilities, item use, multi-shot attacks, and targeted single attacks. They must move around enemies to position themselves for more attack damage and/or minimize defensive damage. There are four positions on a color-coded cardinal wheel for easy reference to determine whether incoming and outgoing attacks will be effective. This mixup of the ATB formula is extremely compelling, as it allows for strategic defensive maneuvers while attacks are charging. Later on, they can also change the dragon’s form to be more defensive, offensive, or agile. These layers of strategy imbue Saga’s combat with a far more robust evolution to the ATB system than anything Square Enix ever published, especially considering their games rarely needed ATB to convey urgency, and hardly used it to full effect (sometimes even blundering with it, as is the case with FFVI‘s Bushido attack). As far as I know, Panzer Dragoon Saga’s innovative battle style has never been used by a game since, which compounds its tragedy, as this gameplay style makes the gorgeous setpiece combat of the game feel surreal yet purposeful.

Speaking of surreal yet purposeful design, PDS’ soundtrack is a place where this combination is deeply present, as the adventurous and strange tone pioneered in the first two games persists here to great effect. Orchestral whimsy meshes with serene vocal flourishes to make a soundtrack that is sonic nirvana. The first two games benefitted from the on-rails nature of the game, as their composers were able to draft a film-like score that perfectly aligned with every moment of play. Even without the rails to guide her here, Kobayashi still manages to transcend those works to create what I consider to be not just the best in the series, but possibly the greatest game soundtrack of all time. Check out “Sona mi areru ec sancitu” and “Ancient Weapon” to see what I mean.

Not to be outdone by the game’s awesome soundtrack, the ending of this game coexists among the “greatest of all time” tier for me as well. As players approach maximum level (and a hidden Panzer Dragoon 1 dragon transformation if they have the insight of series fandom to spur their curiosity), they inevitably grow closer to the final encounter with the Ancient Age’s greatest and most destructive entity, an organic AI named Sestren. Sestren exists between the black tower and an extradimensional space, and the player must drive through Empire forces to reach it. As we get to the familiar locale of the black tower’s center, the dragon feigns a familiar tower-suicide, but the Divine Visitor intervenes. As we cascade into otherspace, the game reveals to us in a spine-chilling Neverending Story-esque mirror gesture that we, the player, are the Divine Visitor. In a world full of hearers, only we had the capacity to listen to the plea of this game: play it. The irony of this is so crushingly palpable when SEGA, hot off of giving Team Andromeda a massive budget and crunching its workers to the literal brink, gave Panzer Dragoon Saga a horribly limited print run (especially in the West), dooming it to obscurity. That a game would conclude with the revelation that players are making the most meaningful interaction they can with their work by simply listening to its tale, only to be purposely silenced by videogame empire, is a crime far more wretched than, say, pirating abandonware. Excuse my partiality.

To make matters worse, the game is now unintentionally being silenced by physical game collectors who remarket their FOMO as “preservation,” yet serve to balloon the price of this game by setting it in their closets in Tupperware instead of playing it and sharing it. Admittedly, even I am culpable in the erasure of Saga, as giving it another glowing retro review may make its collectibility rise. At this point, only SEGA can truly save Panzer Dragoon Saga from the brink; only they can let its poignant player-driven eco-fable coexist among their library of supported SEGA Ages titles. And it is important to save, because it is beautiful to hear, beautiful to play, and damn beautiful to look at.

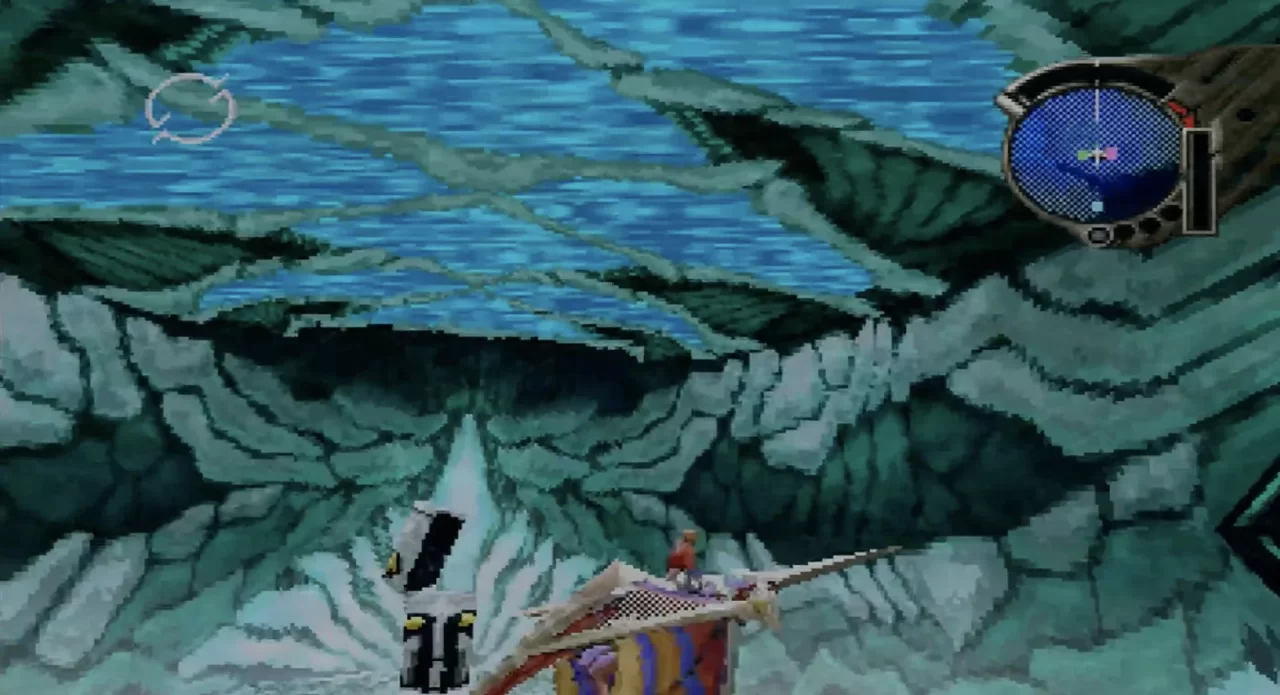

This brings me to the final section of this retrospective: visuals. I often languish in the oversaturated, sometimes illegible worlds of modern AAA videogames. More doesn’t necessarily dictate better. Remasters and remakes like Spyro Reignited Trilogy, Demon’s Souls Remake, and any of Star Fox’s remakes look great in screenshots, but their technicolor flourishes sometimes overpower my senses. Of course, I have played and enjoyed all of those games, and I still cherish their HD-ifications, but I can’t help but feel refreshed when I revisit their ancestors. The thing is, I like a game that looks like a videogame sometimes, and in terms of 3D games, the Saturn and its unique “frame buffer” hardware configuration makes for 3D visual effects that especially give it a videogame vibe. Thus, the jagged rocky tunnels of Panzer Dragoon Saga are about as “gamey” as they come. By “gamey,” I mean that in the same way I can taste the earth that nourishes a “gamey” meat, I can nearly see the bytes behind the textures of Saga’s long, dark hallways.

It’s good that these hallways are fond places for me, because you spend much of this game within them. The world areas between set pieces, boss battles, and the game’s NPC zones are mostly hallways, with a few larger open fly zones sprinkled in. And while the draw distance is not vast and these places are visually similar, I find them to be luxurious hotels for the imagination. Perhaps I am alone in this, but I love a long empty space in a videogame, like God of War’s Desert of Lost Souls, Silent Hill 2’s never-ending stairwell, or Starfield’s expansive planets. I picture myself riding through Saga as if I am in a boundless and deep Valley of the Wind. Nausicaä is a fitting surreal post-apocalypse for this, too, considering it was an inspiration throughout the series for the dev team. I can picture Imperial encampments and civilian settlements behind the rows of flags, piles of clutter, and cave indentations lining Panzer Dragoon Saga’s rocky halls. I can imagine the strange ecosystem that must lie in the black below. This is the upside of early 3D’s gamey surrealism — the surreal challenges the viewer to fill and reason with impossible between-spaces — which is something PDS acknowledges and leans into gracefully. It is a powerful feeling to occupy a surreal space like Saga’s, especially when it not only gestures toward its own surrealism, but also literally toward the player’s involvement in it with its ending. It makes me think that something is lost in the worldbuilding of current AAA games; developers asset-load their games to the point where they no longer invite the player to worldbuild alongside them, only to consume a place they have laid out and manicured to perfection. What if a game could have all the presentation of AAA and still be legible and inviting? I guess I’m saying that Panzer Dragoon Saga is a better videogame than The Last of Us, especially its remakes/remasters.

This isn’t merely a cute way for me to say that I, much like Twin Peaks weirdos who prefer it to The Last of Us or other newer prestige television, am a Panzer Dragoon weirdo who prefers it to The Last of Us or other newer prestige videogames. I also genuinely believe that Saga deserves to be held in the same conversation as any game in the Last of Us lineage of perfect story-gameplay-presentation-artistry mashup games. For the sake of specificity, the games I wager critics would probably place in this lineage are, in order by release date: Another World, Myst, Half-Life 2, Dark Souls, and The Last of Us. These games are astoundingly well-executed pastiches of their own design documents — their gameplay perfectly aligns with their narrative themes, their concept art mirrors their zones/levels, their immersion or flow-state breaking moments are minimal or nonexistent, and their outcomes pretty much always match their intentions. They are perfectly attuned to the grading rubrics of modern videogame graders (i.e. reviewers) who are testing for all these elements. Furthermore, they all carry with them a film-esque cinematic flourish that elevates their storytelling far above the videogame status quo of yesteryear. I believe Panzer Dragoon Saga matches all of these criteria and is more interesting than all of these games.

Firstly, the game broke ground in its use of mo-cap, not just for its sparse pre-rendered cutscenes but also in all of its gameplay. It uses the style of in-engine cutscenes — often using good angles during gameplay rather than gameplay-pausing cinematics — that The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion emulated to award-winning effect eight years later. Secondly, its designers created a custom Japanese-adjacent gibberish language two years before Simlish would do an English-adjacent gibberish language, three years before Dōbutso no Mori (Animal Crossing) would do an any-language-adjacent gibberish language, and six years before Resident Evil 4 would do a Spanish-adjacent gibberish language. Team Andromeda knew that this mystical other-language would be more captivating and immersive than any Earthly language and would fit the surreal vibe of the game better, and it is extremely successful. Pauses between dialogue are never overly videogamely pregnant, as its scenes are well-choreographed, meaning character dialogue takes on an organic plausibility despite the characters speaking a fake language. Games still struggle with this timing today! Thirdly, there is a mechanic that allows players to view objects in a near/far dichotomy, lending lore dumps (through “far” readings) to devoted players while respecting less patient players’ time. Furthermore, NPCs have dynamic pathing two years before Majora’s Mask and eight years before Oblivion. Finally, Panzer Dragoon Saga champions a dynamically strategic turn-based combat style that is yet since unreplicated in any RPG.

In total, PDS does so much to push the boundaries of the industry, making luxurious strides that the industry still struggles to jaunt at, all in service of seamlessly blending gameplay and storytelling. And it does this alongside a story that still rules in a way other games wish they could rule — it has the action chops to please the action fans, the restorative eco-resilience themes to please academics, and the genre-pushing artisanal-ness to please The Game Awards. It never sacrifices atmosphere for non-diegetic over-explanation, never over-tutorializes, and yet its gameplay stays interesting and clear throughout.

Panzer Dragoon Saga does everything a game should do right and more. It is a shame that it is relegated to capital-driven obscurity, because it holds one of gaming’s best stories. In short, Panzer Dragoon Saga is immense, it is tragic, it is titanic.