Starfield is one of the finest playgrounds ever conceived in videogames, and it is a standout title in — and apt reflection of — Bethesda Game Studio’s entire catalog of incredible games. It not only lives up to its own “irresponsibly large” expectations, but it even lives up to a decade of collective anticipation from fans who have been dreaming of “Skyrim in space.”

So I mean it when I tell you I could play Starfield for the rest of my life and be happy. Starfield is, of course, good in all the conventional ways: it has a banger visual style, all the trappings of modern AAA graphics, flawless sound design and music, compelling RPG mechanics, fun storylines, best-in-class dialogue and conversation trees, a robust open world, and is even relatively jank-free. However, the reason I could play Starfield in perpetuity isn’t really because of these elements. It is because Starfield is a masterpiece before any of these elements come into play. At its core, it is the most complete playground for the performance of science fiction role-playing that the videogame market has ever seen. While it certainly succeeds in its efforts to please those seeking a normative linear experience, its focus on player involvement is what makes it worthy of lifelong play.

There are two main ways Starfield focuses on player involvement. The first is more of a side effect of the developer’s mission statement — at least, their sort of unwritten mission statement. As you likely already know, Bethesda Game Studios (BGS) is no stranger to modding. I might even call it a key player in their continued financial success. Their games are always designed with modding in mind (something I think is largely forgotten in the conversation when reviewing their games), and BGS has repeatedly expressed the value they see in their Creation Engine — recently, Pete Hines waxed poetic about BGS’ vision for Starfield modding, claiming players will be able to make their own planets. Of course, modding is not available for the game at launch, so I can’t speak to the accuracy of this claim. However, user-made content is clearly baked into the game’s core design; you can see this in the Creation Engine-focused design. But it is even more pertinent in Starfield‘s second method for player involvement, which concerns worldbuilding, though in a little less conventional, even perhaps groundbreaking way.

Let me lend some context here. In game design (specifically story-driven game design), there are largely two approaches to worldbuilding: the first is called hard worldbuilding — this is where a game designer crafts a fictional space like a blueprint, with exact histories and hard rules for characters, their behaviors, and the places and objects they interact with. The Lord of the Rings is a pretty well-known example of this. The Outer Worlds is another, perhaps more relevant, example of this, with its boutique zones and rigid character roster, both markedly finite. On the other end, games like Control, NieR: Automata, and the Dark Souls series feature soft worldbuilding, or worldbuilding that is more mysterious or unclear, often open for anecdotal interpretations from the player. From a role-playing sense, the former offers a structured fantasy for players to get lost in, whereas the latter is more for those who crave the intrinsic reward of using their imagination.

Starfield is designed to be both one and the other in tandem, making it a compelling playground for all RPG fans. Its exterior is built on hard worldbuilding — its major storylines, underlying lore, and main cast of characters are rigid and structured in an expected way. But its interior is soft in that you can move past its main thread and do whatever you want, and the game will even encourage this. It will nudge you to rush off to uncharted space when hailed by incoming ships, though those same ships are ripe for piracy or battling. When touching down on planets, you get tasks to chart resources, flora, and fauna, and the game rewards players who do so with thousands of credits. Of course, player-driven story design isn’t entirely new, but it is so meticulously executed in Starfield that it feels as compelling and rewarding as this design ever has. It is perfect for a player like me who craves the structure of a large mission now and then, but often just wants to explore space, fight a few pirates, search for meaning in the cosmos, and just vibe in another world. This sort of gumball worldbuilding — with its hard worldbuilding exterior and pliable soft worldbuilding interior — gives Starfield players the meaningful crunch of more rigid and structured story beats, while also giving them long-lasting and flavorful role-playing experiences to chew on after.

This focus on player participation can undoubtedly have its drawbacks. The infamous Bethesda jank is probably the most well-known side effect of this. With such a monumental scope, there are bound to be blemishes — engine bugs, animation issues, crashing, and so on are some of the consequences of making games that let players interact with them at granular levels — you can pick up and move/hold almost any object in their games, for instance. This is, of course, partly because Bethesda dual-launches their games with whatever version of Creation Engine they are using at the time — I can tell you as a former software engineer that this is an undertaking not dissimilar to making two games instead of one. However, it is also because BGS seeks to make games that let players do things like collect a hundred sandwiches in their ship (which some theorize is the reason the Xbox version is capped at 30fps) or stack many multiple styrofoam cups up at one time, which was the obsession of my Neon City Street Rat character Chet Van Jettison, who had only ever seen foam cups in the hands of rich corpos at Neon City clubs, and who craved the soft yet rigid texture of this cheap obsession of the bourgeoisie.

I am happy to tell you this is the least janky Bethesda Game Studios game I have ever played. I know this is like giving the best poop ball prize to a dung beetle, but there it is. If you want an exhaustive list of the crap I encountered in my playthrough, here’s a Starfield jank lightning round (if you don’t care about this, skip to the next paragraph): companions randomly disappear or float (the floating has been mostly fixed). Some confusing early tutorials require powers you won’t have yet. Weapon recoil is unreasonably high early-game. There are unexplained light travel delays and inexplicably long load times in mostly small areas, and the game occasionally doesn’t save when it should (between areas or after 5-minute pause breaks, for instance). Ship storage access is very hidden. Gravity can be inconsistent between planet overworlds and caves. The credits can crash your game, though this has also supposedly been fixed. NPCs’ hitboxes for talking to you are inconsistent and sometimes very large, resulting in too many people speaking at once. Space trash will get “stuck” to your ship and follow you everywhere, companions randomly become bald (seen below), and you can reverse the camera controls in every part of the game except the one thing that needs it: shipbuilding/customization. Still, that’s not that much jank, relatively speaking.

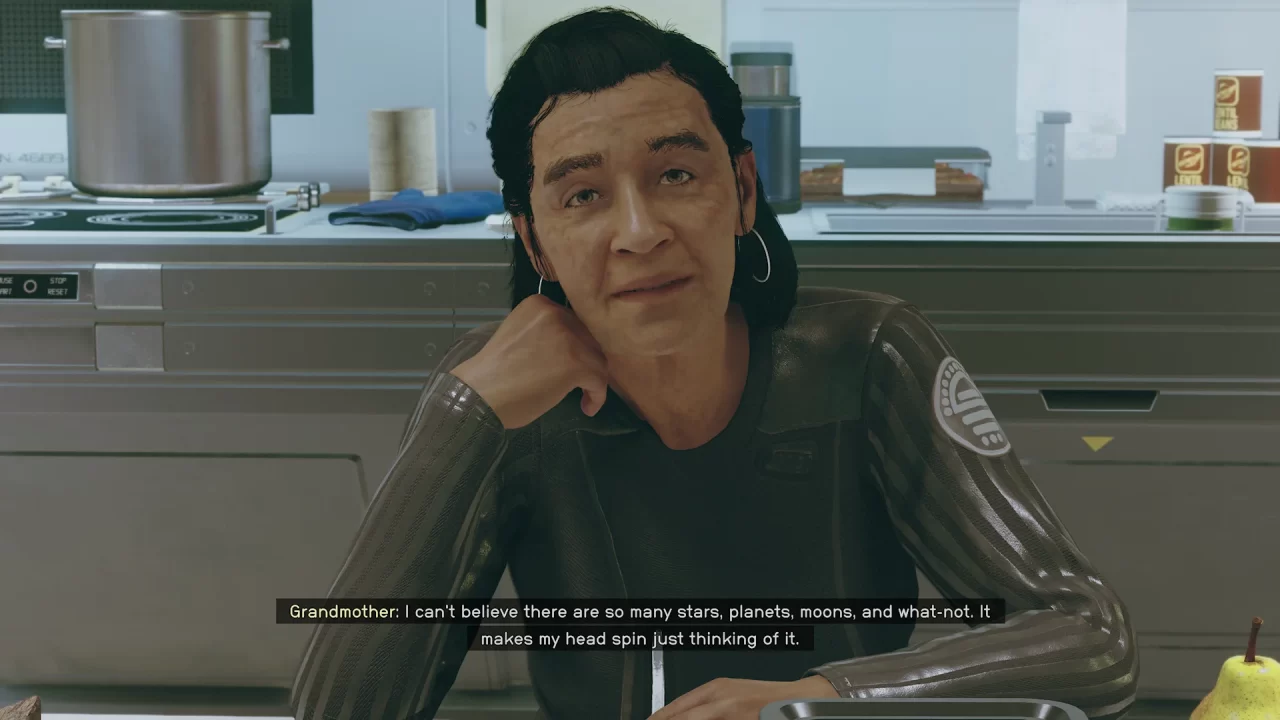

I am also happy to tell you that this game will indulge your every foam cup-collecting, space-pirating, street-ratting character creation fantasy. This is because the character creation options in Starfield absolutely dwarf the game’s contemporaries. There’s a brilliant simplicity on the surface in terms of facial construction and body composition choices and the like, but an ardent face maker can adjust character attributes down to a near-atomic level if they so choose. Beyond this, the games’ classes are meaningful and impact dialogue in pleasantly unexpected ways. For instance, my Neon City Street Rat was able to detect an addiction in an adoring fan of Neon City’s pop star, something I didn’t expect but made sense in the context of that city’s bleak corporate-sponsored drug culture. The same designation allowed me to avoid conflict with pirates and gave me fun dialogue options with several companions afterward. The options afforded by class and specialization ranged from these fun, smaller things to much more melancholic and impactful moments, which I’ll spare here for the sake of spoilers. Overall, though, this attention to detail in character class and customization choices is something other games, such as Cyberpunk 2077, promised but didn’t really deliver on.

This is a theme in Starfield. It delivers on its promises. Where Star Citizen and No Man’s Sky promised a big, well-designed universe, Starfield actually delivers. Where Cyberpunk promised consequences for early player choices, Starfield delivers again.

In this way, Starfield is ambitious, though it is pretty self-aware about it, something reflected in its story. The main story follows the player character as they join an organization called Constellation, which is investigating mysterious artifacts that distort gravity and give those who touch them visions of the scale of the universe. Eventually, these artifacts lead players to Earth, and to a doorway in the center of the universe where they can eventually begin New Game+. There are cheeky environmental storytelling winks along the way, like the use of poetic passages from classic literature that always seem purposefully placed in game areas as metaphors, though they never line up with a relevant scene (which I think is hilarious). The story itself is sort of about the development process of Starfield, too. It riffs off the iteration of a game space through its New Game+ mechanic, which is compulsory to the story. I would almost say the game begins after the first NG+. There is also the side bit about Earth, about things coming apart under the gravity of their own weight, something I have to think reflects back to that “irresponsibly large” comment from Todd Howard. It just seems too convenient that this is a game about the responsibility of taking on an enormous starborne project when there is potential for something smaller and perhaps more meaningful at home.

This awareness is key to the quality of the experience. You can tell that BGS is aware of the state of things in the industry, and of the monumental pressure they are under to deliver something stable and compelling, at the risk of losing even more faith following Fallout 76 and the length of time between release windows of their hot IPs like The Elder Scrolls. You can also tell that they know a thing or two about the NASA-core aesthetic they are inhabiting. The game looks like an old NASA pamphlet, but it is also colorful and particle-rich, gorgeous even in the most lush areas such as New Atlantis, arguably its “main hub,” if it had one (though my main hub was Neon City, I admit). Its space combat is frenetic and similarly visually gorgeous, something in tune with the compelling combat of games like Star Wars: Squadrons.

This attention to detail extends particularly to the game’s sound design. Notwithstanding the instant classic soundtrack — that rivals Oblivion‘s for me — the ambient sounds and voice acting in the game are immaculate. The sound of a ship arriving in the distance is one of the purest pleasures I have had in gaming in years. The way it crackles and burns into the landing pad sends shivers up my spine every time, even after 50+ hours of play. I feel like Molly Shannon in Talladega Nights every time — oh I love when them ships whiz by! There is something so satisfying about docking into a space station, hearing a ship slip into hyperspace, or the sound of lasers rolling past your head in combat. Even more satisfying is that every line of dialogue in this game — of which I hadn’t heard more than a handful repeated in my long playthrough (there must be tens of thousands of lines of dialogue here) — is fully voiced and very well-acted.

I have to hand it to Starfield. It delivered on its promises, and maybe a little more. It hosts a remarkably immersive, player-focused game space, and I am captivated by all elements of its design, even its blemishes, of which there are fewer than expected. It is a game whose components are captivating alone but greater than their sum. Somehow, it crafts a near-infinite space for play, but it leaves more still for players to explore. And it does so in interesting and innovative ways, almost reflecting back on itself as if it were Constellation, whose motto is appropriately “infinitum addendum,” or what we are adding to infinity.

Author’s Note: The code I received worked on both Xbox Series X and PC, and the game performed really well in both cases. I preferred it on PC, where I played in 1440p at 60fps, as opposed to Xbox, which was 4K but only 30fps. There may have been a few additional visual glitches on PC, but otherwise, there was no difference performance-wise (I am using a pretty powerful computer with an RTX 3080 graphics card and ran the game at max settings with no problem). I was even able to get Starfield running on my ROG Ally very briefly, though it was quite compromised and eventually stopped working altogether, which I won’t attribute to the game itself but to the console’s hardware limitations and outdated graphics drivers (which were just announced hours before we published this review). Starfield is a very cutting-edge game that will require a lot of computing power to play. Transferring cloud save files between console and PC also worked fine, though it took ages for me.