And now for the words that every potential reader loves to see at the beginning of a review: It’s time for a history lesson!

Before graphical point-and-click adventure games, we had narrative text adventures. In these games, players read descriptions and input instructions via a text parser, using their keyboard to navigate the world with commands like “Go east” or “Go west.” To get your character to actually perform an action in these games, you would literally need to tell them exactly what you want them to do. To pick up an item, you would type “Get ye flask,” often to have the text parser respond with something like, “You cannot get ye flask,” or “I don’t understand that command.” Though text adventures offered enjoyable experiences for the time, technological limitations held them back from being more immersive. Enter graphic adventure games like King’s Quest! Adding pictures to the equation suddenly opened up entirely new avenues of storytelling, even though the gameplay was still arguably held back by limited text parser systems (Gameplay innovations like verb menus were yet to be created by Ron Gilbert and Gary Winnick in 1987’s Maniac Mansion).

For many folks, text parser adventure games are ancient video game history, but for others, these formative games provided extraordinary interactive experiences that should be remembered, celebrated, and even iterated upon in the modern era. Solo developer Julia Minamata is one such person. In her attempt to create a pitch-perfect homage to Sierra-style adventure games—specifically those from legendary adventure game designer Roberta Williams—she developed something that transcends its origins to become one of the best pieces of video game pastiche I’ve ever played: The Crimson Diamond.

It’s Ontario, Canada in 1914, and the country is at war with Germany. Amid this chaos, Nancy Maple, an aspiring geologist at the Royal Canadian Museum in Toronto, is sent to Crimson, Ontario, an old garnet mining town, to investigate the possible discovery of diamonds in the area. Once there, Nancy sets herself up at a run-down wilderness lodge filled with potentially sinister customers, all of whom share and hide secrets. After the only bridge out of Crimson is destroyed in a suspicious manner, Nancy decides to put aside her geological work and instead uncover who committed this crime and why. In doing so, she uncovers a conspiracy that could have far-reaching implications for the success of Canada and the Allies in the First World War.

One of the problems with modern games that are “inspired” by classics is that many of them never actually live up to their inspirations. It turns out that what those games did, what makes us remember them, was extremely hard to pull off! And while these pale imitations can offer fun experiences, they are rarely timeless in the same way as their originators. This is not one of those games. The Crimson Diamond understands what made its inspiration, primarily the Laura Bow Sierra games, so compelling. It then improves on that formula to deliver something that doesn’t only evoke Sierra-style text parser adventure games but, in many ways, transcends them to provide something eminently playable for audiences today.

The first thing The Crimson Diamond does right is offer the most painless text parser I have ever used, then or now. It’s incredible how quickly this archaic and often obtuse input method becomes natural to use, much more so than you would expect from its appearances in retro titles. It goes to show what some developers back in the late ’80s and early ’90s could’ve done with a little more storage space! I was constantly delighted by how many potential responses are programmed into The Crimson Diamond. If you tell Nancy to do something, she will do it if she can. And if she can’t do it, she will tell you why. For example, if you ask her to hit somebody, she will say that she doesn’t have it in her to be violent. It’s hilarious and beats the heck out of the game telling you, “I don’t understand what you mean.”

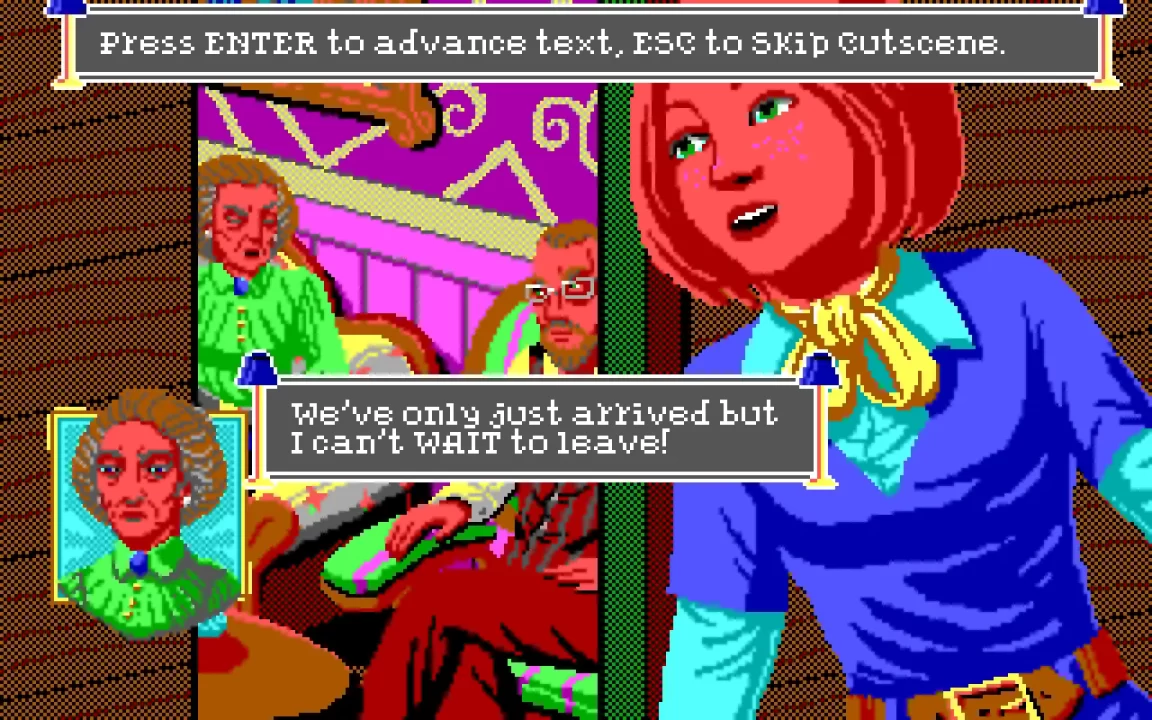

The other reason why The Crimson Diamond is a pitch-perfect pastiche is because of the graphics, sound, and cutscenes. Perfectly emulating the EGA graphics used in the era, the game is limited to the same 16-color palette used in the original Laura Bow title, The Colonel’s Bequest. The result is stunning pixel art that resembles another era of gaming while standing apart as a clearly modern interpretation. For one thing, the game is widescreen. Character designs are unique and instantly identifiable, both in their cutscenes and in their character sprites on the screen. The music and the sound effects also benefit from this careful attention and sound exactly like the beeps and bloops that would come from a terrible speaker in a giant gray box wheezing underneath a CRT monitor. Julia Minamata’s attention to detail in making this game look and sound authentic to the period is breathtaking, showing an incredible depth of artistic skill when designing the game’s assets.

But what about the gameplay? This game puts a Canadian spin on the classic British murder mystery setting of being trapped in a manor during a snowstorm. Here, it’s a wilderness lodge, and the train bridge is out, leaving everyone trapped with the criminal. This setting provides a limited number of potential locations, giving the game a manageable sense of scale. All you need to do is look around every location at the lodge, and you will eventually find the answer—providing that you also figure out the phrase necessary to do what you want. This is still a point-and-click, so you can click where you want to go. However, I found using the arrow keys on the keyboard much more intuitive, further evoking the feeling of nostalgia that permeates the entire presentation.

Death scenes are one of the most famous parts of Sierra-style adventure games. If you took a wrong step, fell into a river, or stumbled into danger unprepared, you could rely on a death screen showing up saying, “Better luck next time: Load, Restart, or Quit.” In this era of gaming, auto-saving wasn’t a thing, which meant that if it had been a while since you last saved, you might have to repeat hours of progress to get back to where you made that first mistake. The Crimson Diamond pays homage to Sierra-style death scenes; however, they are played more for laughs than anything. The game auto-saves before each death, allowing you to jump right back in and try again. This makes each death scene feel more like Easter eggs and fun rewards to seek rather than genuine setbacks.

Another aspect of Sierra adventure games forgotten about in the modern era is the point system. In LucasArts games, there was usually a set path from beginning to end, with no real deviation from this path. In many Sierra-style games, however, you could easily miss clues, points of interest, character interactions, items, and other events that would improve your endgame score. The Crimson Diamond puts its own spin on this system. While you can solve the mystery 100% without finding everything, there are certain mysteries and character motivations that you cannot solve if you miss crucial scenes or clues. This is a delightful way to get more replay value from a genre that notoriously lacks it.

Nancy Maple is a joyful protagonist who feels pulled right out of classic Sierra titles. She shared many similarities with her redheaded inspiration, Laura Bow, but she brings her own strengths. Nancy is a scientist who prides herself in empirical thinking, living in an age when women were usually not given responsibility or credit for their abilities. Yet she keeps trying, eventually winning over the support and admiration of most other folks at the lodge, and even her boss at the museum. The other characters vary in depth; some are fully fleshed out, while others remain sketches. I do wish we got to explore the motivations of some of the more antagonistic characters in the lodge more. I would have also preferred fewer “endings” to the game. The number of times I thought the narrative had reached its conclusion only to continue for several more scenes rivals The Lord of the Rings: Return of the King in terms of its inability to complete the story! Thankfully, the final ending does deliver a heartfelt and satisfying conclusion to the game; I just wish they got to it quicker.

The Crimson Diamond is a remarkable game, not just in terms of the experience it offers, but in the fact that it exists at all. The game not only successfully evokes text parser adventure games of decades past but improves on them in dozens of little ways. Julia Minamata deserves a massive amount of credit for evoking the feel, look, and style of the era in a way that doesn’t feel dated or like a relic of a forgotten past. Whether her next project is a text parser game, a verb-wheel-based point-and-click, or a completely different genre, I expect she will make it with the same level of care and imagination that she shows here. The Crimson Diamond is clearly a labor of love, and I loved it just as much in return!