“I think everybody has that one video game; the one that sticks with them long after the credits roll and inspires them to take up a new hobby, or live their lives a little bit differently.” This is the opening line to Videoverse, and by no means do I think creator Lucy Blundell—aka Kinmoku—intended this to reference their own game. But…it could totally apply to Videoverse.

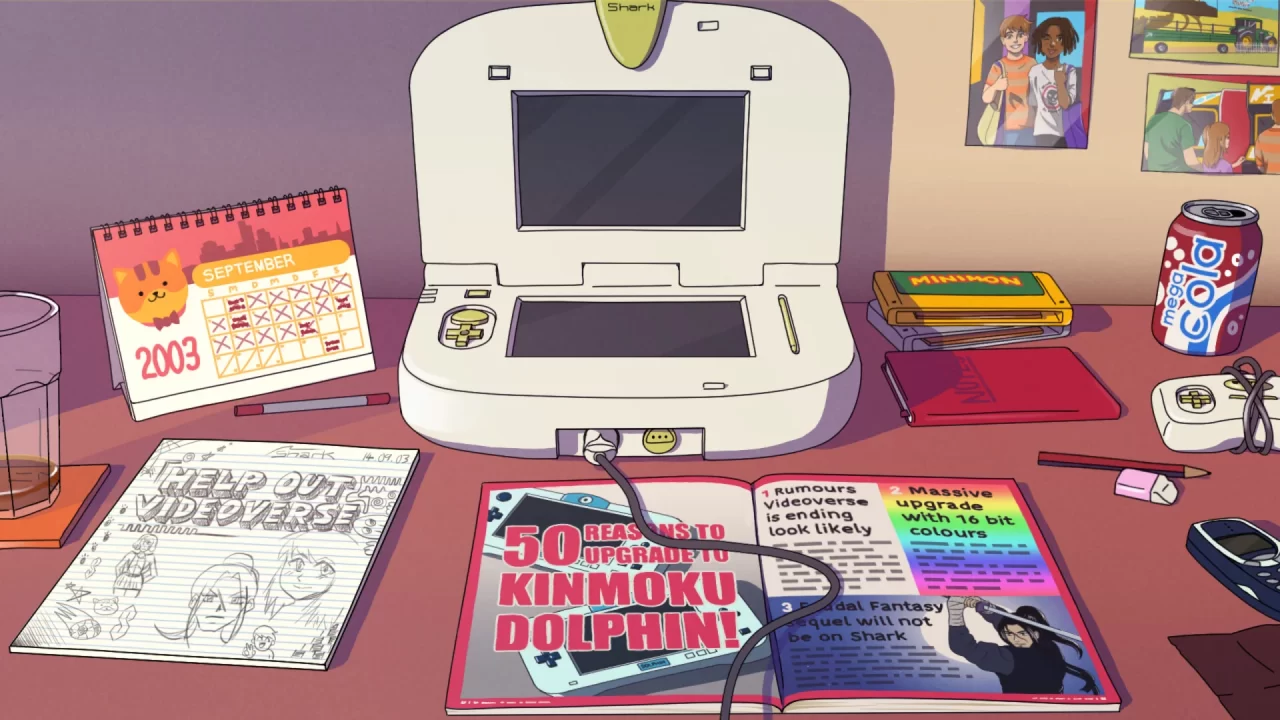

Videoverse is a five- to eight-hour visual novel that takes place entirely through an old Internet chat interface known as Videoverse. Think something akin to Internet forums, chat programs, or messengers circa the late 1990s and early 2000s. An adult Emmett, the player character, looks back on his teenage years in 2003 as he recalls the people he met on Videoverse. Players will find themselves either trying to make the program and community the best it can be or tear it down—or maybe something in between.

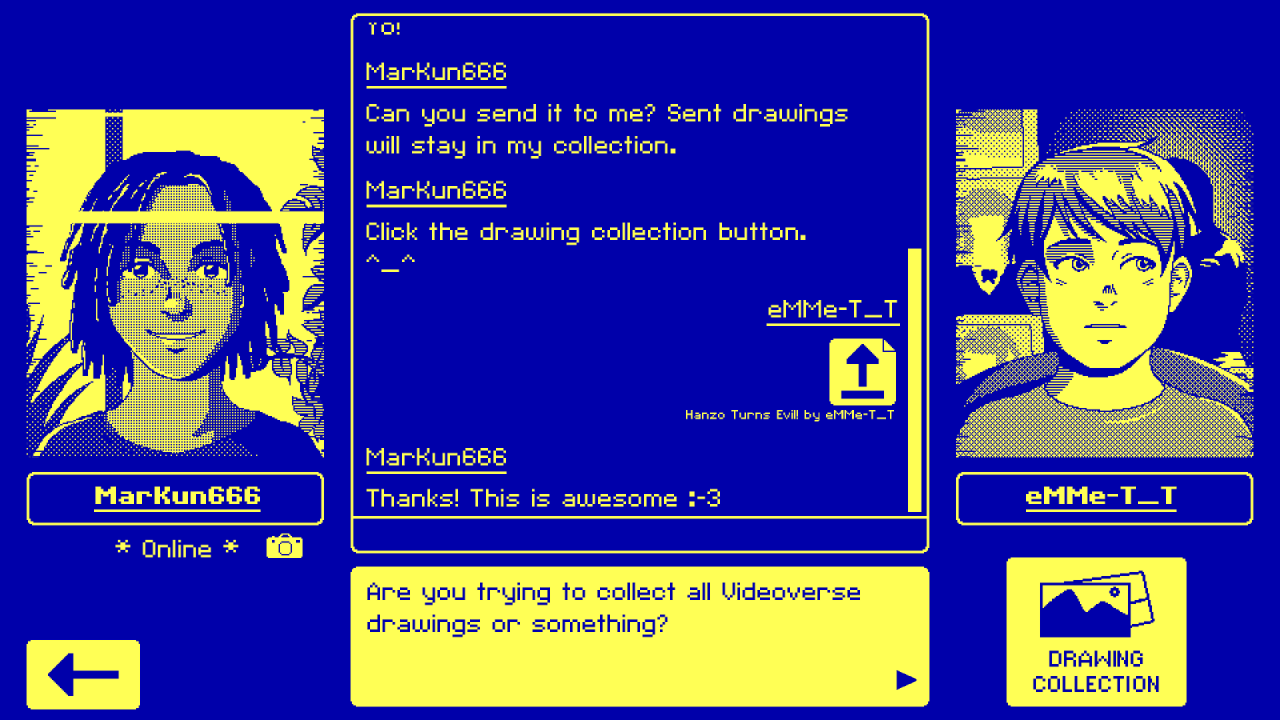

Most gameplay involves liking posts or reporting ne’er-do-wells per the Kinmoku—the in-game developers of Videoverse—guidelines; no swearing, spoiling games, or general poor behavior. Every day, Emmett goes to different community areas to respond to a string of posts with familiar faces. Players will soon recognize certain names and avatars cropping up occasionally; each has a distinct voice and personality. Some communities involve off-topic posts, fandom surrounding a hit video game (Feudal Fantasy), and a place to post artwork created on the platform.

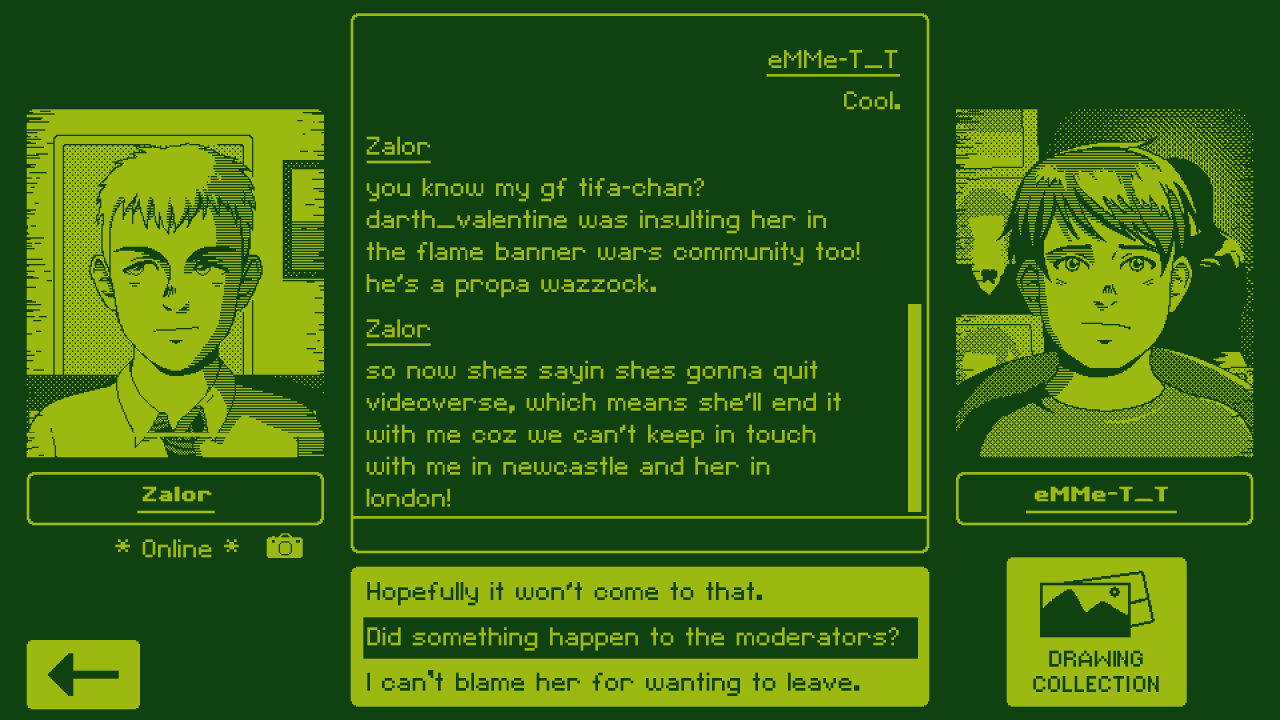

While interacting with the Internet forum feels authentic and engaging in its own right, the rest of the gameplay takes place in a messenger, where Emmett types to or video chats with friends. Emmett’s got his core couple of people he has known for years and some he has even met, and he gets to know some new folks over the course of the game. Eventually, Emmett decides on side quests to improve the community by watching out for troublemakers, keeping an eye on people who don’t seem to be doing well emotionally, or supporting his friends in some way, like sharing drawings with them.

Early into the game, Emmett’s entire world and priorities shift when he meets a new user named Vivi. Something about Vivi strikes Emmett, and we get to observe—and take part in—his budding friendship with this mysterious person. Gradually and with outstanding pacing, we get more and more information about her as she comes out of her shell. Naturally, all does not go smoothly, as is the case with any relationship worth investing in, and we bear witness to some of the most immersive dialogue and storytelling I’ve experienced in years.

All that I’ve described so far might not sound entirely exciting—the content is ostensibly lackluster, but where Videoverse shines is the execution. This is Lucy Blundell’s second game, yet they have the storytelling prowess of a veteran author. I’ve rarely encountered people in a video game who feel so tangible and real, including some of the tertiary characters. Being maybe a little too honest, it’s probably because I feel like I’ve lived this life, at least in some fashion. Reader: maybe you have, too.

And you’ll know it pretty early on. Videoverse might be the most authentic piece of fiction I’ve experienced that nails those old Internet feelings. If you’re somewhere between “adult finding stability in your life” and “old fart” like me, you know this world. If you struggled with dial-up Internet that kicked you off every couple of hours, and you threw a thick blanket over your modem at 2 AM so your parents wouldn’t wake up hearing it reconnect, you know this world. If you had a crew online that you were just as thick with as your friends at school, you know this world. Calling Videoverse a period piece may be laying it on a bit thick, but there is absolutely and truly no game I’ve ever played that has taken me back to these days like Videoverse has. I remembered people and places I hadn’t thought about in literal decades.

If you’re not old enough to have body aches for no reason, don’t worry, Videoverse is still a fantastic tale for folks of all ages. In fact, the challenges faced and teenagers Emmett engages with are so natural in both Internet speak and in conversation over messenger, that I think everyone knows the joys and woes expressed in this brief narrative. Topics involving sexuality, family drama, disability, mental health, and ageism are handled exquisitely in that I never felt like Blundell was preaching, but they were addressed tactfully and with the importance they deserve. The discussions around these topics aren’t always kind, but that’s also authentic to the Internet—as we all know. Yet, here we have the opportunity through Emmett’s hands to either add fuel to the fire, lambaste the cruel, or serve as a beacon of positivity and example.

I’m burying the lead, though: while Videoverse is largely about old Internet programs and the impact of growing technology on communities and culture, it is also about love, healing, and the bonds that can happen over a series of tubes. Emmett’s young love with Vivi becomes the centerpiece of Videoverse; after all, love is the greatest thing in the world, and who knows that better than teenagers? (That isn’t dry sarcasm, by the way.) While Emmett by no means has a bad life, he’s at that critical age where that intimate bond with another becomes all-consuming, bordering on obsession. Yet Vivi doesn’t know. We witness the spar between the two: a constant guessing game of feeding each other kindness and wondering how the other feels. A harsh comment here or sudden disconnection there leaves us worrying about what the other person is thinking or if we somehow unwittingly ruined something precious. All of the scenarios and opportunities set up create dramatic tension that, again, is expertly paced and deliciously uncomfortable as Blundell leads us on the wonderful mystery known as reciprocation. We join Emmett on the tumultuous journey as we pivot and prod, choosing what we hope is the correct dialogue option to win Vivi over.

And while Emmett has friends on Videoverse to provide perspective and advice, we, the player, have Clark Aboud, who has composed one of the most outstanding soundtracks I’ve heard in any video game. The tunes are by no means complex or brimming with evocative instrumentation, but rather couple the charming 1-bit graphics with MIDI-like audio quality. Ambient in nature and the perfect accompaniment to each interaction, Aboud’s work breathes mood and power into a story already brimming with both. His work is a testament that an outstanding video game soundtrack doesn’t need horns, strings, or a full orchestra: it just needs the right feeling when paired with its game.

Videoverse has to be one of the most authentic time travel pieces of media I’ve ever experienced. I’ve played countless games that lean heavily on nostalgia—oftentimes cheaply—to try to make me feel like a kid again or at least like I was immersed in something similar to those RPGs of yore. Videoverse might be the only title to truly accomplish that. It’s no accident that I was pulled back to my tender teenage years and remembered things I hadn’t for so long. My only quibble—and I hate to say it—is the ending, and that isn’t even to say that it was a bad ending, but it wasn’t the ending I wanted. I also felt like the ending did not explain enough, or at least some of what occurred didn’t make sense to me after the game had otherwise deftly executed each story beat and conflict. Or maybe I didn’t pick up on some subtlety to beautifully explain why this or that happened. Regardless, the ending is moving in its own way and may suit most others just fine. It also doesn’t diminish the quality of the entire story told, the characters I fell in love with, or the fictional place I had spent countless hours in as a youth. If ever there was a game that makes a case for Internet communities and video games as tools for healing, this is it. Thank you from the bottom of my heart for this gift, Lucy Blundell.