LnRiLWdyaWQsLnRiLWdyaWQ+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1pbm5lci1ibG9ja3M+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1ibG9jay1saXN0X19sYXlvdXR7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtcm93LWdhcDoyNXB4O2dyaWQtY29sdW1uLWdhcDoyNXB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWl0ZW17YmFja2dyb3VuZDojZDM4YTAzO3BhZGRpbmc6MzBweH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW57ZmxleC13cmFwOndyYXB9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPip7d2lkdGg6MTAwJX0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi10b3B7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LXN0YXJ0fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWNlbnRlcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmNlbnRlcn0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1ib3R0b217d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LWVuZH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9IjNkOWMzOTlmZTYyNWUxYjk3MmY4MTdhMDY4MDIyOWY2Il0geyBncmlkLXRlbXBsYXRlLWNvbHVtbnM6IG1pbm1heCgwLCAwLjVmcikgbWlubWF4KDAsIDAuNWZyKTtncmlkLWF1dG8tZmxvdzogcm93IH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9IjNkOWMzOTlmZTYyNWUxYjk3MmY4MTdhMDY4MDIyOWY2Il0gPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoMm4gKyAxKSB7IGdyaWQtY29sdW1uOiAxIH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9IjNkOWMzOTlmZTYyNWUxYjk3MmY4MTdhMDY4MDIyOWY2Il0gPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoMm4gKyAyKSB7IGdyaWQtY29sdW1uOiAyIH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW49IjMwMzRmYmU4ODZjMTEwNTRlOTViNDZiMDlkM2U0MTEyIl0geyBkaXNwbGF5OiBmbGV4OyB9IEBtZWRpYSBvbmx5IHNjcmVlbiBhbmQgKG1heC13aWR0aDogMTAyNHB4KSB7IC50Yi1ncmlkLC50Yi1ncmlkPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItaW5uZXItYmxvY2tzPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItYmxvY2stbGlzdF9fbGF5b3V0e2Rpc3BsYXk6Z3JpZDtncmlkLXJvdy1nYXA6MjVweDtncmlkLWNvbHVtbi1nYXA6MjVweH0udGItZ3JpZC1pdGVte2JhY2tncm91bmQ6I2QzOGEwMztwYWRkaW5nOjMwcHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1ue2ZsZXgtd3JhcDp3cmFwfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj4qe3dpZHRoOjEwMCV9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tdG9we3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1zdGFydH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1jZW50ZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpjZW50ZXJ9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tYm90dG9te3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1lbmR9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSIzZDljMzk5ZmU2MjVlMWI5NzJmODE3YTA2ODAyMjlmNiJdIHsgZ3JpZC10ZW1wbGF0ZS1jb2x1bW5zOiBtaW5tYXgoMCwgMC41ZnIpIG1pbm1heCgwLCAwLjVmcik7Z3JpZC1hdXRvLWZsb3c6IHJvdyB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSIzZDljMzk5ZmU2MjVlMWI5NzJmODE3YTA2ODAyMjlmNiJdID4gLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uOm50aC1vZi10eXBlKDJuICsgMSkgeyBncmlkLWNvbHVtbjogMSB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSIzZDljMzk5ZmU2MjVlMWI5NzJmODE3YTA2ODAyMjlmNiJdID4gLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uOm50aC1vZi10eXBlKDJuICsgMikgeyBncmlkLWNvbHVtbjogMiB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbltkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPSIzMDM0ZmJlODg2YzExMDU0ZTk1YjQ2YjA5ZDNlNDExMiJdIHsgZGlzcGxheTogZmxleDsgfSAgfSBAbWVkaWEgb25seSBzY3JlZW4gYW5kIChtYXgtd2lkdGg6IDY0MHB4KSB7IC50Yi1ncmlkLC50Yi1ncmlkPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItaW5uZXItYmxvY2tzPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItYmxvY2stbGlzdF9fbGF5b3V0e2Rpc3BsYXk6Z3JpZDtncmlkLXJvdy1nYXA6MjVweDtncmlkLWNvbHVtbi1nYXA6MjVweH0udGItZ3JpZC1pdGVte2JhY2tncm91bmQ6I2QzOGEwMztwYWRkaW5nOjMwcHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1ue2ZsZXgtd3JhcDp3cmFwfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj4qe3dpZHRoOjEwMCV9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tdG9we3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1zdGFydH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1jZW50ZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpjZW50ZXJ9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tYm90dG9te3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1lbmR9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSIzZDljMzk5ZmU2MjVlMWI5NzJmODE3YTA2ODAyMjlmNiJdIHsgZ3JpZC10ZW1wbGF0ZS1jb2x1bW5zOiBtaW5tYXgoMCwgMWZyKTtncmlkLWF1dG8tZmxvdzogcm93IH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9IjNkOWMzOTlmZTYyNWUxYjk3MmY4MTdhMDY4MDIyOWY2Il0gID4gLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uOm50aC1vZi10eXBlKDFuKzEpIHsgZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46IDEgfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW5bZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj0iMzAzNGZiZTg4NmMxMTA1NGU5NWI0NmIwOWQzZTQxMTIiXSB7IGRpc3BsYXk6IGZsZXg7IH0gIH0g

LnRiLWdyaWQsLnRiLWdyaWQ+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1pbm5lci1ibG9ja3M+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1ibG9jay1saXN0X19sYXlvdXR7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtcm93LWdhcDoyNXB4O2dyaWQtY29sdW1uLWdhcDoyNXB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWl0ZW17YmFja2dyb3VuZDojZDM4YTAzO3BhZGRpbmc6MzBweH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW57ZmxleC13cmFwOndyYXB9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPip7d2lkdGg6MTAwJX0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi10b3B7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LXN0YXJ0fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWNlbnRlcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmNlbnRlcn0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1ib3R0b217d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LWVuZH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9IjNkOWMzOTlmZTYyNWUxYjk3MmY4MTdhMDY4MDIyOWY2Il0geyBncmlkLXRlbXBsYXRlLWNvbHVtbnM6IG1pbm1heCgwLCAwLjVmcikgbWlubWF4KDAsIDAuNWZyKTtncmlkLWF1dG8tZmxvdzogcm93IH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9IjNkOWMzOTlmZTYyNWUxYjk3MmY4MTdhMDY4MDIyOWY2Il0gPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoMm4gKyAxKSB7IGdyaWQtY29sdW1uOiAxIH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9IjNkOWMzOTlmZTYyNWUxYjk3MmY4MTdhMDY4MDIyOWY2Il0gPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoMm4gKyAyKSB7IGdyaWQtY29sdW1uOiAyIH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW49IjMwMzRmYmU4ODZjMTEwNTRlOTViNDZiMDlkM2U0MTEyIl0geyBkaXNwbGF5OiBmbGV4OyB9IEBtZWRpYSBvbmx5IHNjcmVlbiBhbmQgKG1heC13aWR0aDogMTAyNHB4KSB7IC50Yi1ncmlkLC50Yi1ncmlkPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItaW5uZXItYmxvY2tzPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItYmxvY2stbGlzdF9fbGF5b3V0e2Rpc3BsYXk6Z3JpZDtncmlkLXJvdy1nYXA6MjVweDtncmlkLWNvbHVtbi1nYXA6MjVweH0udGItZ3JpZC1pdGVte2JhY2tncm91bmQ6I2QzOGEwMztwYWRkaW5nOjMwcHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1ue2ZsZXgtd3JhcDp3cmFwfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj4qe3dpZHRoOjEwMCV9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tdG9we3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1zdGFydH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1jZW50ZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpjZW50ZXJ9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tYm90dG9te3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1lbmR9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSIzZDljMzk5ZmU2MjVlMWI5NzJmODE3YTA2ODAyMjlmNiJdIHsgZ3JpZC10ZW1wbGF0ZS1jb2x1bW5zOiBtaW5tYXgoMCwgMC41ZnIpIG1pbm1heCgwLCAwLjVmcik7Z3JpZC1hdXRvLWZsb3c6IHJvdyB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSIzZDljMzk5ZmU2MjVlMWI5NzJmODE3YTA2ODAyMjlmNiJdID4gLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uOm50aC1vZi10eXBlKDJuICsgMSkgeyBncmlkLWNvbHVtbjogMSB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSIzZDljMzk5ZmU2MjVlMWI5NzJmODE3YTA2ODAyMjlmNiJdID4gLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uOm50aC1vZi10eXBlKDJuICsgMikgeyBncmlkLWNvbHVtbjogMiB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbltkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPSIzMDM0ZmJlODg2YzExMDU0ZTk1YjQ2YjA5ZDNlNDExMiJdIHsgZGlzcGxheTogZmxleDsgfSAgfSBAbWVkaWEgb25seSBzY3JlZW4gYW5kIChtYXgtd2lkdGg6IDY0MHB4KSB7IC50Yi1ncmlkLC50Yi1ncmlkPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItaW5uZXItYmxvY2tzPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItYmxvY2stbGlzdF9fbGF5b3V0e2Rpc3BsYXk6Z3JpZDtncmlkLXJvdy1nYXA6MjVweDtncmlkLWNvbHVtbi1nYXA6MjVweH0udGItZ3JpZC1pdGVte2JhY2tncm91bmQ6I2QzOGEwMztwYWRkaW5nOjMwcHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1ue2ZsZXgtd3JhcDp3cmFwfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj4qe3dpZHRoOjEwMCV9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tdG9we3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1zdGFydH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1jZW50ZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpjZW50ZXJ9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tYm90dG9te3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1lbmR9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSIzZDljMzk5ZmU2MjVlMWI5NzJmODE3YTA2ODAyMjlmNiJdIHsgZ3JpZC10ZW1wbGF0ZS1jb2x1bW5zOiBtaW5tYXgoMCwgMWZyKTtncmlkLWF1dG8tZmxvdzogcm93IH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9IjNkOWMzOTlmZTYyNWUxYjk3MmY4MTdhMDY4MDIyOWY2Il0gID4gLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uOm50aC1vZi10eXBlKDFuKzEpIHsgZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46IDEgfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW5bZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj0iMzAzNGZiZTg4NmMxMTA1NGU5NWI0NmIwOWQzZTQxMTIiXSB7IGRpc3BsYXk6IGZsZXg7IH0gIH0g

Open-world games are far from uncommon in the modern gaming landscape, but when it comes to JRPGs, there are far fewer offerings that allow freedom on such a scale. If there is one thing that Square Enix excels at, it’s coming up with innovative and fresh takes on the JRPG genre. Starting with 1987’s now-legendary Final Fantasy, which drew heavy inspiration from games like Dungeons & Dragons and the Ultima series, non-linear JRPGs have been evolving and finding new ways to give gamers a say in how everything plays out. While the kind of open-ended storytelling that tabletop gaming is famous for is impossible to fully realize digitally, the ambition to come as close as possible has been shaping JRPGs for decades. Akitoshi Kawazu, the mastermind behind the SaGa series, perhaps appreciates this method of game design more than most. First appearing in 1989 as a Final Fantasy spin-off, SaGa (localized as The Final Fantasy Legend in the West) quickly developed its own identity, in no small part due to Kawazu’s ideas.

Akitoshi Kawazu’s Influence

In an interview with Forbes, Kawazu stated that his favorite game was Ultima IV: Quest of the Avatar and went on to explain its significance. According to Kawazu, prior to that game, “‘there were only two things that a video game provided players: the satisfaction of winning, and basking in the sense of accomplishment after completing the game.'” Through Ultima IV, Kawazu soon realized that concepts like character building and freedom to choose one’s path could be utilized in his own games, and he has since been finding ways to implement value to the player beyond the basic goal of completion. Kawazu went on to add that “‘[t]here naturally were various ways in which you could achieve this depending on the game, but overall the ways in which you could enjoy games back then was more limited.'”

True to Kawazu’s take on ’80s and ’90s game design, there were considerable hurdles presented by the hardware in those days. In that same interview with Forbes, Kawazu stated that initial brainstorming for Final Fantasy Legend involved a choice between venturing underground to defeat a demon or climbing a tower to face a god. Due to the memory capacity of the original Game Boy and production costs, they were forced to choose one of the two scenarios. While there isn’t much that developers can’t accomplish these days given adequate resources, the limitations of the past have become that much more significant in that they forced developers to come up with more creative solutions. Gradually, this began to change with the advent of more powerful consoles. By the time the original PlayStation rolled out, it was possible to make games much more open-ended. Once again, Kawazu’s SaGa series sat at the forefront of experimental, non-linear JRPGs.

SaGa Frontier

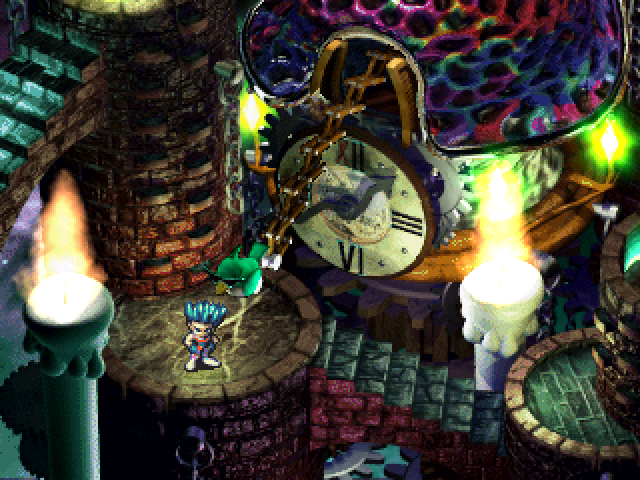

On the surface, SaGa Frontier may seem like any other JRPG of the late ’90s; it certainly has a lot of the same trappings. At its heart, however, it is a meditation on how to create a complex web of characters and settings within the constraints of the PlayStation’s capabilities, and how to do so in a way that feels natural. Boasting seven separate protagonists, each with their own story and flavor, along with a non-linear world that could be explored largely at will, it was something that many at the time had not seen before in a JRPG.

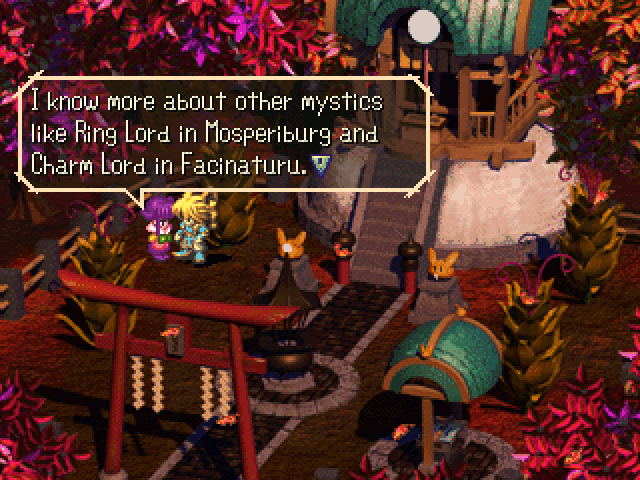

While SaGa Frontier does not have fully open-world levels of freedom, the choice of where to go and what to do outside of advancing the plot is entirely up to the player. The different areas you can visit, known as “regions,” are small pieces of a complete world that remain mostly consistent throughout each character’s scenario. The locales visited in a particular scenario may be identical on the surface, but the individual scenarios that play out within them are often unique to each protagonist. Perhaps some of the magic of the game is not so much that it gives the player freedom to explore at will, but rather the cohesive nature with which the world and characters come together.

In a case of art imitating life, imagine that you interact with seven distinctly different people over the course of a day. Think about how vastly different they can be, and how your conversations change — sometimes dramatically — based on who you’re chatting with. The things you say to a childhood friend are wildly different than how you speak to a customer at your job. This is part of the principle at work in SaGa Frontier, and it is a huge part of the charm of revisiting each region as a different character. It always feels like there is something new to discover about a place you thought you already knew. The ruin that is a mere footnote in one protagonist’s adventure could be (and often is) a major setting in another’s story. The strange bit of scenery that doesn’t totally fit but lacks an evident purpose? Don’t be surprised if you learn its function while playing as different character.

Of course, not all details in the game that seem relevant have a purpose. As with the unrealized alternate scenario in its predecessor, The Final Fantasy Legend, one of the more fascinating tidbits about SaGa Frontier is just how much unused content it has. This is yet another area in which technology limited an ambitious project. Despite the controversial opinions surrounding DLC in the modern era, games like this one could have benefited greatly from the option. Rather than wrapping up what they could in the time given, future patches or DLC could have been implemented to allow the game to exist in its intended form.

The combat system in the game also draws from the concept of choice. Kawazu envisioned a system wherein repeatedly performing certain actions in battle would raise a character’s stats. Someone who uses swords might gain points in strength, while magic users would gain points in intelligence. First implemented in 1988’s Final Fantasy II, it instead became a mainstay of the SaGa games, picking up additional features such as learning skills through actions taken in battle. In an interview with 1UP.com, Kawazu stated that due to Final Fantasy II having a greater focus on story than its predecessor, specific characters were needed to fill particular roles. This raised the question of how to make a character with a predefined personality feel like your own. Kawazu’s solution was to foster nurture over nature: “‘You don’t choose what you are in the beginning. You make them grow in a certain way and then they’ll eventually go in a direction to become whatever you set them up to be….It’s not something you decide at the beginning. The character-building process goes through the entire game.'” Can it be said that growing as a person in real life is any different?

By today’s standards, SaGa Frontier is far from a perfect game. However, it certainly accomplished what it set out to do, evoking feelings of freedom within a limited medium and laying the groundwork for non-linear JRPGs to come. Kawazu himself described it best in his 1UP.com interview: the unifying theme of the SaGa series is “‘[a]llowing the players to play the game the way they would like to play it. Giving them freedom to take the game in the direction they want to take it, without interfering too much on the design side.'” No matter how much our games may change over time, that same spirit of adventure keeps bringing us back, eager to discover our own unique stories.

Sources: Forbes, 1UP.com (via Retronauts)