As a little kid growing up on the PlayStation 1 and my father’s NES, I was accustomed to replaying the same short experiences again and again. Not knowing how to work a memory card—and fearful of overwriting dad’s Metal Gear Solid save—I was content to start my handful of games fresh each day. If it was a long summer day, I may have even seen the end of the game or else risk letting the console spin all night to continue in the morning. Like movies, games were short, direct experiences I relished replaying, likely because my young, tiny brain couldn’t absorb all that was being offered.

Maybe it went hand-in-hand with the longing for freedom as I aged, but I began to crave more substantial, in-depth games. A key moment was when an older friend I looked up to gave me a copy of Final Fantasy X. This wasn’t like my dad’s old games or a game I shared with my brother—this was my world to explore. Somewhere between the PS2 and PS3, I became more isolated in my little fantasy worlds and enjoyed the long escapes they afforded me. The simple act of wandering in worlds far away from my small Canadian town was an allure of its own. That was around the time I began retroactively playing the great JRPGs that had always been there, with their enigmatic covers taunting me from the shelves of my local rental shop. Two nights, or even a week for the golden oldies, was never enough time to complete a Final Fantasy or a Chrono Trigger, oh no. These were nearly year-long commitments for me, like starting a series of tome-like fantasy novels, and I loved them for all their mileage.

Worlds of Illusion

In the nearly twenty years since, I’ve revisited many of the JRPGs I once inhabited, only to be shocked at how quickly they can be cleared. It’s a humbling experience to see a game that took you ages now reduced to a single, twenty-hour longplay video on YouTube. Replaying Final Fantasy III through IX, especially, I realized that the open worlds were never really as open as I was led to believe. Instead, you have overworld continents that may be barren save for a town or two, random encounter battles, and pixelated clumps of mountains, forests, and the occasional desert bottlenecked at either end with what is likely a cave dungeon to take you to the next empty continent. Turn those random encounters off (as recent re-releases of Square Enix games, in particular, allow you), and you quickly realize that these overworlds are little more than vast hallways guiding you to the next plot point.

Had I been lied to all along? Am I just now seeing through the matrix? Or has adult me, no longer a free time millionaire, become so jaded by a multitude of RPG experiences that I’m impatient and no longer drawn in by the joy of discovery? Instead, I’ve concluded that the physical size of the world was never actually what drew me in.

It’s easy to see why so many people think that being big and open are what immerse us in RPGs. Most would agree that the strongest point of any traditional JRPG are the endgame chunks just after you get to pilot your version of an airship or dragon and have free rein to visit any point in the world. By that point, your party is strong enough to forgo the chore of walking and battling random monsters. Wandering is streamlined—and see! The game is arguably at its most fun! And yet, it wouldn’t be the same just giving the player the airship right from the get-go, would it? The villages and dark towers you fly over would hold no personal significance, no memory of collecting your ragtag band of heroes one by one and increasing their strength and abilities. Were I to fly anywhere I wanted from the start, who’s to say I don’t end up in the highest-level zones and get my party wiped by a king behemoth or a mandrake marshal? Game Overs and getting so lost you have to look up a guide? Immersion-breaking. If given the choice to do objectives and story chunks out of order, too many games have proven to leave side characters out of important story beats. So many Chrono Cross, Suikoden, and Octopath Traveler characters with absolutely nothing to say? Immersion-breaking. All that to say that, a tunnel, if cleverly shaped and disguised, is often the most enjoyable way to explore a game world.

Let’s look, then, at Final Fantasy X and its lush world of Spira, a beautiful and convincing series of stages devoid of any standard overworld. Revisit its locales on foot after you’ve played through most of the story, and you’ll find yourself running from the beaches of Besaid to the neon-tinged Macalania Woods and to the snowy peak of Mt. Gagazet within mere minutes of each other. Even the airship you finally gain control over simply takes you through a text list of save spheres and drops you off immediately. And you know what? Despite this, Spira feels like one of the most living, breathing game worlds I’ve ever played. FFX‘s story ushers you through a mostly linear tour of its grand sites with express purpose—in this case, defending the summoner Yuna on her holy pilgrimage—and never feels restrictive or lacking in freedom. It feels big without making me walk through every square foot of it.

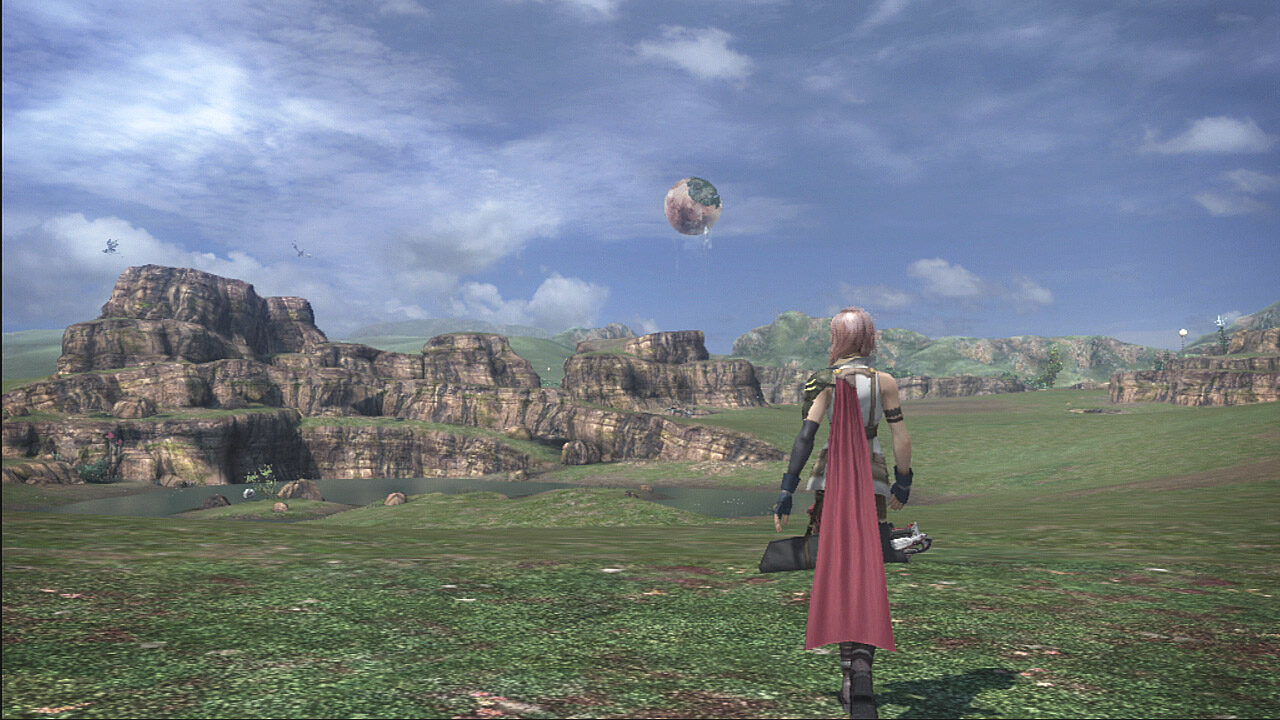

Compare FFX with its gawky younger sister: Final Fantasy XIII, a game ripped apart for its blunt linearity (among other issues). The ovular locales of FFX are tightened in XIII to more narrow corridors just a few character models wide, the random encounters replaced with on-screen wandering enemies to confront. If we think back on the earliest Final Fantasy titles as players in metaphorical paddle boats, aimlessly moseying around a mostly empty lake with a few interesting docks at either end, then FFXIII had the potential to be a Disneyland dark ride a la Pirates of the Caribbean. I think Square Enix saw the trend of their narrowing world design and took a big swing, reducing the JRPG formula to its most bare components. The result was a visually and musically stunning on-rails, linear ride…that simply goes on too long for its cramped nature. And what makes it feel so cramped is that it doesn’t even try to hide the linearity. In actuality, it’s not so much more restrictive than FFX. But whereas the camera jumps from fixed angle to fixed angle in Spira, giving Tidus’ journey more dimensions and directions, Lightning can freely move the camera, despite your movement always pointing forward down the long expanse of monster-filled tunnels of Cocoon. There’s little suggestion of a world beyond the crosshairs of your gunblade.

By the time Lightning and co make it to Chapter 11, the game does open up to a semi-open world with its own “airship moment,” but I suspect few players stuck around long enough to enjoy it. And even then, this moment simply turns a hallway into a large, mostly empty field. Is that any more fun? Would Final Fantasy XIII have done better as a truncated, 12-hour experience? Perhaps, but that would leave a lot of worldbuilding to the visual storytelling and go against the patient, progressively building gameplay that seems a staple of RPGs worldwide. FFXIII is so high-octane that it rarely allows quiet, slower moments to digest and care about the characters, their turmoil, and the larger world. There are little to no towns I can remember the name of. Instead, you get battle after battle, and yet the game takes far too long to let you fully wield its great Paradigm battle system. Ultimately, both FFX and FFXIII have roughly 45-hour-long stories, but the latter feels much longer. Linearity isn’t the main issue—monotony is. And monotony can creep its way into any game, no matter how cramped or how vastly open.

Journeys From the West

Something changed the RPG landscape in the years leading up to Final Fantasy XIII, and it didn’t happen in Japan. Properly starting with the explosive success of Bethesda’s The Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind in 2002 and even more so with The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion (2006), Western open world RPGs became as mainstream as Madden. Seriously, even jocks in my high school took the day off to play Skyrim when it came out in 2011 (11-11-11, who could forget?). Western RPGs have always emphasized player choice more than JRPGs, but suddenly the greatest joy was found in skipping the main story altogether and exploring huge maps full of sidequests that often don’t feel “side” or second banana to the main quest. I consider the success of Bethesda’s post-Morrowind Elder Scrolls and Fallout games to be benchmarks not only in RPGs, but in all of game design, considering how in the console generations since, for better or for worse, 100-plus hours of side content has become a selling point of many genres.

But in the case of The Elder Scrolls or Fallout, is it the wandering, or is it the freedom that people enjoy? Sure, discovering a settlement after dozens of minutes of stumbling through a wasteland is a rewarding experience, but I’m willing to bet few choose to retread ground they’ve passed after unlocking fast-travel options—just like with JRPG airships! My point is, it’s the moments of RPGs that stick with us, not the commuting between the moments. The size of a game world does not a game world make. It’s the careful design and planning of the experiences within that world, the characters, the music, the gameplay. In the case of Western RPGs, those moments tend to be the choose-your-own-adventure power fantasies of nameless, lone-wolf protagonists who act as surrogates for the player. In JRPGs, memorable moments tend to be scripted melodrama, catchy music, and the mathematical min/maxing of classes and inventory systems.

Consider the open world influence on Japanese games since the 2010s: Capcom’s Dragon’s Dogma (2012), Konami’s Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain (2015), Nintendo’s The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild (2017), Sega’s Sonic Frontiers (2022), and FromSoftware’s Elden Ring (2022), to name a few notable examples. All veer pretty strongly from the tried-and-true formulae of their predecessors to varying success. Then there’s Square Enix’s Final Fantasy XV (2016), which drops you and your squad of bros in a huge desert and immediately gives you a ton of sidequests to chase after. With FFXV, the developers misinterpreted Western RPG freedom as “which mundane fetch quest or hunting bounty do you want to run to now?”, and what should have been a direct response to complaints around the linearity of FFXIII (which is ironic, considering FFXV started development as “Versus XIII”) turned into a real monkey’s paw, with far too many hours of walking diffusing the many strengths of the game. This time, we’re just not jogging through the corridors of Cocoon—enjoy jogging through the desert, boys! And to briefly bookend the mainline series, Final Fantasy XVI (2023) is a monster of a game with about 15 hours of incredible story and pomp and boss fights that I wish I could replay, allowing that I could trim off over thirty hours of lukewarm filler.

Open worlds are not inherently empty, as some of the games above prove. Walking in games is not inherently boring (“walking simulators” are some of my favorite games!). Prioritizing quantity over quality in game design, however, misses the things that truly make us love and want to live in RPGs. You don’t need to force me to step on every inch of your world; you just need to creatively immerse me in the larger implied world. The bigger you bloat a map, the more you risk it feeling empty or breaking immersion. Perhaps that’s just a response to the growing cost of game development and the need to pad games to justify the price tag. However, I’m much more likely to revisit or recommend a shorter, tightly crafted, thoroughly positive gaming experience than a rambling behemoth of a game.

To tie it back to my younger self, I suspect it was never the actual act of wandering around Final Fantasy overworlds that drew me in, but the glimpses of those rich, evoked universes between the pixels and the polygons and the way they continued to live with me long after I put the controller down.