War. War never changed. Fallout 2 never got an expansion pack.

A lot has changed since Fallout 2‘s 1998 release, even in the world of the Fallout series. It is a product of its time in that, along with Diablo, Fallout and its sequel set the tone in a new way for modern CRPGs, feeding into the series cousin and successor, the legendary Baldur’s Gate. Instead of drawing on Western fantasy, as most of the RPGs before it, Fallout 2 continues the degenerative path blazed by its predecessor in a mix of sci-fi and futuristic fantasy now known as postapocalyptic. It’s weird to think about Fallout 2 being limited because of technological restrictions at the time of its release. On the contrary, the Fallout games pushed what was even possible back then. What Fallout 2 lacks in technical prowess, it makes up for in allowing its players freedom, with so many branching paths that it’d take a long time to see everything worth seeing.

Much like Mad Max, the movie series from which Fallout 2 primarily takes its inspiration, you’re an inhabitant of a wasteland that purportedly used to be the United States, except in this case, it’s hundreds of years after civilization has fallen. In fact, it’s an expansion of so many things from George Miller’s original trilogy—from the style, with the one-armed leather jackets, spiky shoulder pieces, generally violent nature, and general dustiness, to the ideas of settlements in conflict over resources. Similarly to Fallout, you’re a member of a tribe nearing total disaster, and the elder tasks you with finding a Garden of Eden Creation Kit (GECK), which, by the sound of it, would bring restoration in some way. In a callback to the first game, the original Vault Dweller’s jumpsuit with “13” on the back is hanging in a shrine, a relic from the events of the first game 80 years prior. Since it’s your turn to save your people, you put it on and head out into the wasteland.

Fallout 2, naturally, builds on everything its predecessor set up, with more densely populated locations and deeper stories, both in the main quest and in the diversions along the way. It stretches much of what the first game brought to ridiculously creative degrees, including some of the most colorful companions in the entire series. The early stages of wandering to different locations and getting involved in everything from joining the mafia to being sheriff for a day to being the giver of life or death to so many people are enjoyable for how many possible directions you could choose in any situation. You can be creative when finding solutions to your problems. But even the first portion of the game is only a warmup for the stellar 5- to 10-hour final push to the quest that completes it. It’s always astounding to see how a game from that time weaves together the connections between so many moving parts in its world. Some random encounters are fun and exciting because they’re so varied and dynamic, and you can join in your own adventures with many of the groups you encounter on the road, from slavers to cattle drivers.

Especially from a modern perspective, Fallout 2 carries over the same frustrations as the first game. Much of its notorious difficulty stems from the random encounters you experience on the road. The traveling segments are mechanically similar in their oppressive nature to Oregon Trail‘s, except with deathclaws, which are somehow deadlier than dysentery. While the many deaths you experience from the horrible things you find on the road accentuate the wasteland’s inherent danger, it’s also purely frustrating. You rely on luck to eventually discover the breakthrough you need—whether it’s a piece of armor or a weapon—to make real headway. You have to go into it with the mindset that you’re going to die a lot, and there’s nothing you can do about it, which can be discouraging. The fact that you face this kind of trouble at the beginning is tough enough, but that you can experience it every time you try to make your way to a new part of the map gets old. Being successful in Fallout 2 almost necessitates having a self-deprecating sense of humor or at least an indomitable will to push onward in the face of great adversity.

Some aspects of the hex-based tactical combat were innovative for its time, namely the VATS system, which allows for targeting enemies’ individual limbs or head. Overall, however, I never found combat to require all that much strategy. Whether you win or lose is mainly determined by your level and equipment, and it’s also down to luck whether you can run away if the odds aren’t on your side. Of course, it’s fun when you can use whatever shiny new gun you just acquired to tear apart enemies who used to do the same to you, which makes your character’s growth satisfying.

It’s also exciting to get a taste of what else is out there and get hit with a sense of wonder at discovering something new (and deadlier than you’d ever expected) or to see a group of raiders fighting a bunch of radscorpions (then picking up the spoils yourself later). It’s also weirdly heartening to know that any horrifying death contraption you see human enemies using, you will someday have access to yourself. That’s why this system works at times, despite itself. It’s nice that what you need to get through the game is supplied to you in the locations you visit, but it’s even more frustrating that you must suffer through the wasteland portions to get to that point.

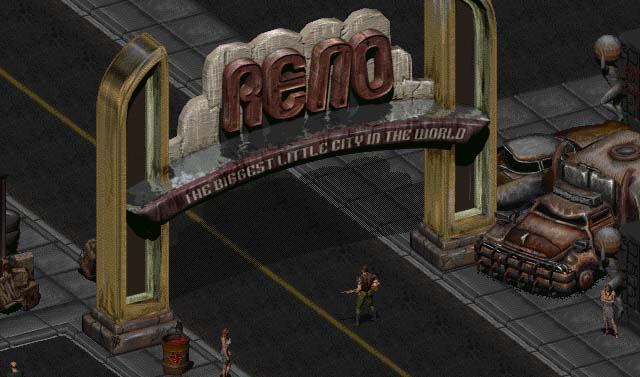

Fallout 2 is unique from the Bethesda games in its scope, taking place across a large swath of the Western U.S. It’s a massive area compared to the later games (at least the base game), which stick to a single city and its outlying areas. Your date tracker shows that traveling takes several days, and your overall quest takes years to complete. I relocated to Nevada a couple years ago, and I enjoyed seeing that Reno’s “Biggest Little City in the World” sign is spared from the nuclear destruction and lives on in New Reno. And I wouldn’t ever want to cross that desert on foot.

Fallout 2 also feels dated in aspects beyond the graphics and design philosophy. It’s great that it doesn’t take itself too seriously and handles everything it touches with a smirk. But it gives into that late ’90s demand for shock value for those who thought Jerry Springer and Pulp Fiction were so smart for exploiting taboo topics, with all the smugness of that smiling Vault Boy mascot. For instance, there are sex workers in most towns whom you can hire for their services, but the game doesn’t delve into that subject any deeper than surface level. A few pop culture references that may have been fun at the time but feel quite dusty today also date the game. Finding references to Monty Python and the Holy Grail in a two-decade-old game, while inoffensive, might be a sign to current creators that those kinds of references might not hit the same way in the future as they do now.

That said, some of the political commentary in Fallout 2 hits its target and is timeless, smartly handling large-scale conflicts, both cold and hot. It’s telling that groups of people seen as less human or nonhuman, the outcasts and outliers, tend to handle their societies in less destructive ways than the squabbling humans who consistently believe they have all the right answers. For Fallout fans, Fallout 2 reveals some aspects of the world that color the rest of the series. You won’t miss out on anything vital by not playing this game, but it does illuminate some interesting facets of this futuristic world. That makes Fallout 2 worth checking out for hardcore players who have only played Fallout 3 onward.

Even for the obvious visual limitations of the time, much effort still went into the game’s appearance. Characters and items have a rounded look that tricks the eye into thinking there’s more depth to the two-dimensional sprites than there actually is. The environments are fine, and there are some distinctive areas and structures, but much of the textures are copied and pasted, so many areas look the same. The audio is excellent. Voice acting is only available for a handful of important characters, but it’s impressive for the time. Even the video cutscenes still look great for what they are. The music is atmospheric and mostly unintrusive. The sound team knew to save their best for when they needed to hit you, using a simple yet ominous rising tone that brings goosebumps. Sadly, Fallout 2 is missing the series’s trademark song, “I Don’t Want to Set the World on Fire” by the Ink Spots. Instead, it includes “A Kiss to Build a Dream On” by Louis Armstrong, which keeps the setting grounded in its Golden Era aesthetic.

Despite some elements that don’t hold up decades later, Fallout 2 still holds a lot of fun for those willing to push through its frustrations. Fans of later Fallout games, especially those curious about what came before, owe it to themselves to give into that curiosity because Fallout 2 will handsomely reward them—if not in bottle caps, then in some lore that takes the series even higher. It’s remarkable what the Black Isle crew pulled off so long ago in creating a system that allows so much freedom in character creation and decision-making before those elements became standard in CRPGs. Even if they didn’t want to set the world on fire, they still did.