FEBRUARY 1945, TINGLEV, DENMARK — Though the war was raging hundreds of miles away, we never expected it to come to our sleepy little town. But five years after the Gestapo arrived, our quiet way of life was no more. The warmness of our community, which once cut through the bitterest of winters, was replaced by frosty danger lurking all around. Though I’d known everyone here since birth, I am now unsure how much I can trust anyone. I’m no spy, no combatant, just a nurse trying to do her job – caring for people who need help. But doing so may force me to take measures beyond the walls of my clinic.

In Gerda: A Flame in Winter, you take on the role of the game’s namesake, Gerda Larsen, a young woman living in a small Danish town near the German border in 1945, during the height of World War II. The seemingly inconsequential village of Tinglev has become occupied by Nazi soldiers, and the Danish Resistance (among the first in Europe during the war) is firmly established and trying to liberate the town. It’s a war story that takes place far from any major front; still, the conflict that historically touched the farthest corners of the continent comes to Tinglev anyway. Gerda is no soldier, yet she is drawn into the town drama and gets caught up in a struggle to keep herself and her loved ones alive.

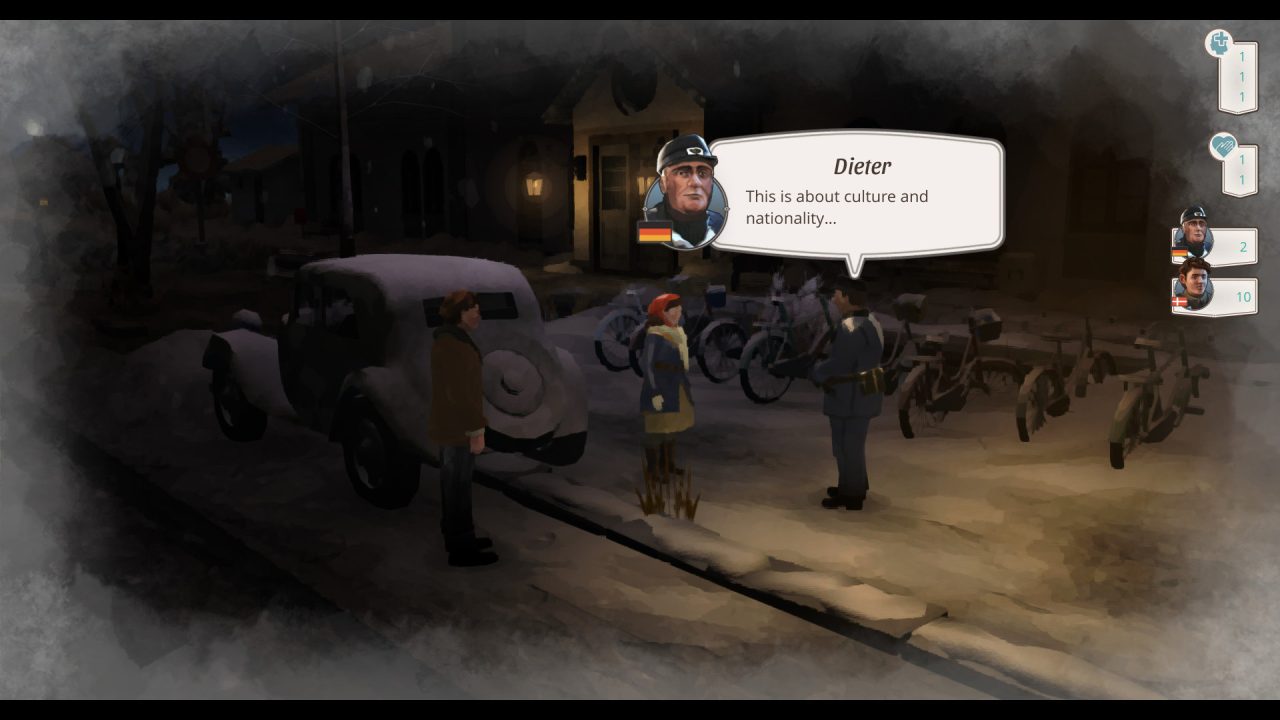

Setting the story of Gerda: A Flame in Winter at the border makes for a tale naturally rife with tension between supporters of either side and odd allegiances. Gerda, being the daughter of a German and a Dane and also married to a Danish man, contains a war within herself. Her father, Dieter, though loving of his family, is openly supportive of the Nazi party; her husband, Anders, is devoted to his country and holds a few secrets. You serve almost as Gerda’s conscience, guiding her thoughts, feelings, and actions. Despite one side in this conflict being the Gestapo, the choices are never easy. With the caring spirit of a nurse, Gerda’s aim in all of this is to protect human life on all sides. The fictional Tinglev itself feels like a living entity, but the opposing forces are tearing it apart, and Gerda takes it upon herself to try to hold it together.

Gerda: A Flame in Winter is full of fascinating characters, each with complex motivations. Surprisingly, some of the most multifaceted personalities in this story belong to Nazi characters whom Gerda must deal with. Though many stories in the West treat Nazis as cartoonishly evil and completely irredeemable (and make no mistake, the movement was wholly morally reprehensible), it’s interesting to have Nazis who are fully fleshed-out characters. They hold motivations and desires that often have little to do with toeing the party line. Gerda’s cousin, Charlotte, is a secretary for the local Gestapo group. She’s not a proclaimed Nazi herself, but she’s doing it because she “needs the job.” But Gerda becomes concerned, as the longer Charlotte stays in that position, the more their conversations suggest sympathies for Nazi ideology. One of the most captivating characters is Reinhardt, a Nazi soldier with allegiance to no one but himself yet develops an odd relationship with Gerda over mutually beneficial propositions.

The excellently written characters weave into a firecracker of an espionage and secrecy story, a social minefield that Gerda must cross as delicately as possible. Introductions to all of the main players happen early, and each of them leaves a lasting impression. From there, it’s situation after situation of pitfall-filled conversations and potentially dangerous consequences. I got a small sampling of the pressure of living under a fine microscope, with both the Gestapo and the Resistance scrutinizing every move I made. Even talking to the wrong person can upset the polarized forces at work in Tinglev. Even though the second half of the narrative pushed too quickly toward the ending, Gerda: A Flame in Winter had its hooks in me from the start. I did find the twists to be predictable, but the depth of the characters and the intense situations push the story beyond its formulaic boundaries.

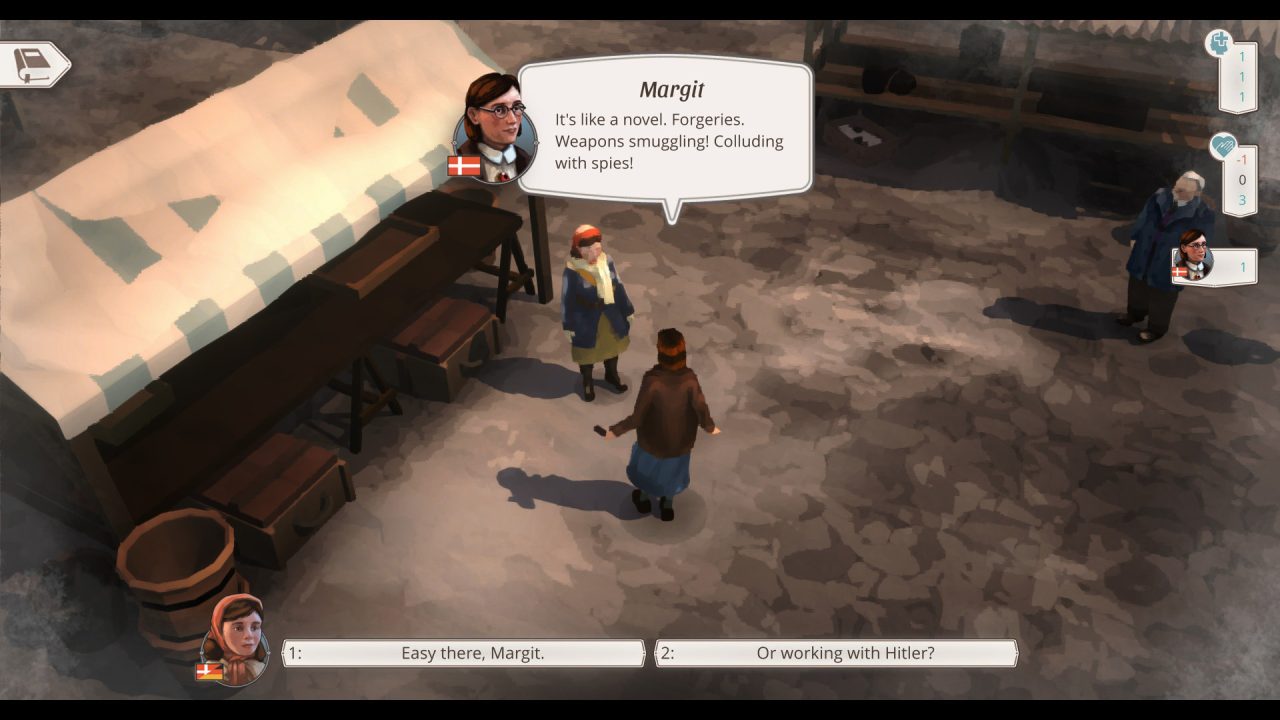

Gerda: A Flame in Winter plays much like a Telltale game or DON’T NOD’s other games, though there’s some wonkiness to address later in this review. You can choose where to go, whom to talk to, and which places to investigate. Each day, there are several locations you can visit where an event will occur. However, you have a limited amount of time, so you can’t visit all of them. You have many options as to how to respond in conversations, but the social atmosphere is quite touchy, considering the situation. Each named character or movement (pro-German or pro-Danish, for example) has a Trust level that is often affected by your choices. The Trust level is vital to pay attention to because attempting more difficult social plays in conversation will be more or less available depending on how much the other person trusts you.

Thus, there’s an underlying tension in every choice you make. Early in the game, I thoughtlessly started talking to everyone and looking at everything, as I would in any RPG or adventure, and that got me into trouble that I wasn’t intentionally looking for. In some conversations with Nazis, I attempted to appease them to try and keep the peace and to gain their trust for leverage later. Unfortunately, doing so had the unwanted effect of upsetting the Resistance. At one point, it began to feel like I was making all the wrong choices, but c’est la vie. Failure in Gerda: A Flame in Winter tends not to be as fortuitously acceptable as in Disco Elysium, but it’s also not a total death sentence, at least not immediately. Again, these situations are so wonderfully tense that I was fully dialed in, feeling like I was in my own spy thriller, and I didn’t want to set the game down.

On the flip side, some aspects of Gerda: A Flame in Winter’s gameplay felt ajar, mostly involving the Trust score. Characters’ trust level with Gerda is represented as a numerical score. That looks and feels weird thematically. Whenever you’re interacting with a character, a tab on the side of the screen pops out showing how your relationship has changed. It looks silly, especially when you’re in a conversation with several characters, with multiple tabs moving back and forth repeatedly. Practically, it’s understandable that developers would want players to know exactly where they stand with certain characters because trying for a difficult conversation choice requires a dice roll, with misses causing a bad outcome. But instead of telling you the number you need to hit, you’re given a general description of how difficult your play would be, defeating the purpose of the precise numerical score anyway. It would have felt more immersive to have your relationship status be descriptive — i.e., “distrusting or “very distrusting” — rather than numerical, so it would feel less like doing algebra. The developers were in the right ballpark here, but it’s disappointing that this system didn’t gel more smoothly, as it should be a driving aspect of the design. The Trust number display is a light shade of blue, which is difficult to see from far away.

Gerda: A Flame in Winter is beautiful to the eye. Though PortaPlay developed the game, its watercolor-like visuals align with DON’T NOD’s other titles. Instead of dynamic camera angles, as seen in games like Life is Strange, the view is always isometric in Gerda: A Flame in Winter. There’s also a constant frost effect around the edges, accentuating a setting so cold you might get frostbite just from looking at it. Unfortunately, the game looks much better when it’s still than in motion. Gerda, in particular, walks with a waddle, and other characters similarly have odd-looking movements. The music is on the simpler side, mostly featuring a single piano, though the performer succinctly expresses the mood at hand, whether occasional tranquility or a sense of underlying danger.

While the spy story of Gerda: A Flame in Winter is thrilling, the narrative also effectively strikes to the heart of why Nazi propaganda was so effective. Though he’s not a violent man, Dieter is easily persuaded to join their ranks because the Nazis reach him at his most basic level: pride in one’s country and protection of one’s family. The Resistance, on the other hand, does themselves no favors with their violent tactics and brutal purges, doing little to differentiate themselves from the Nazi occupation. Gerda desires no part of any conflict, but merely cooperating with the Nazi oppressors, even to get through her day in peace, unwittingly aids their cause. It’s a horribly unenviable situation. Gerda: A Flame in Winter is vastly different from other World War II stories, with its setting far from any battlefield. It demonstrates how fully the Nazis had engulfed Europe during the war. In the US, we rarely see this perspective in media or education, so this story illuminates a part of history many of us might not otherwise experience.

Though the game can be completed in under ten hours, Gerda: A Flame in Winter contains multitudes beneath its exterior. I was held in suspense even when I had to shut the game down to go about my life. The choose-your-own-adventure gameplay style made me feel responsible for Gerda’s well-being and the people around her, even as her life was spinning out of control. Though not everything works and the narrative feels slightly too short, it’s also a wild ride that should satisfy those who enjoy the twists and turns of a hearty spy story. The world was a cold and cruel place during the Second Great War, and Gerda: A Flame in Winter provides an intense glimpse of how it felt to live back then.