Sega famously and successfully branded itself as the anti-Nintendo during the Genesis era, and Landstalker is their anti-Zelda. Landstalker is the punk-rock response to The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past’s dad-rock. If A Link to the Past is Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon, Landstalker is Never Mind the Bollocks, Here’s the Sex Pistols. It’s abrasive, esoteric, yet full of an infectious and unique energy. What I’m trying to say is that I love Landstalker (like its musical analogue) but I wouldn’t recommend it to everyone.

I grew up with A Link to the Past (ALttP) and continue to appreciate its thoughtful design, mythological tone, and general respect and care towards its players’ experience. On the other hand, this was my first time playing Landstalker, and despite working with similar Zelda-like conventions, it offers a completely different kind of experience on all fronts. I’ll be drawing out the comparison throughout this review as I think it will give readers who haven’t played Landstalker a clearer way to gauge whether its general design philosophy will appeal to you.

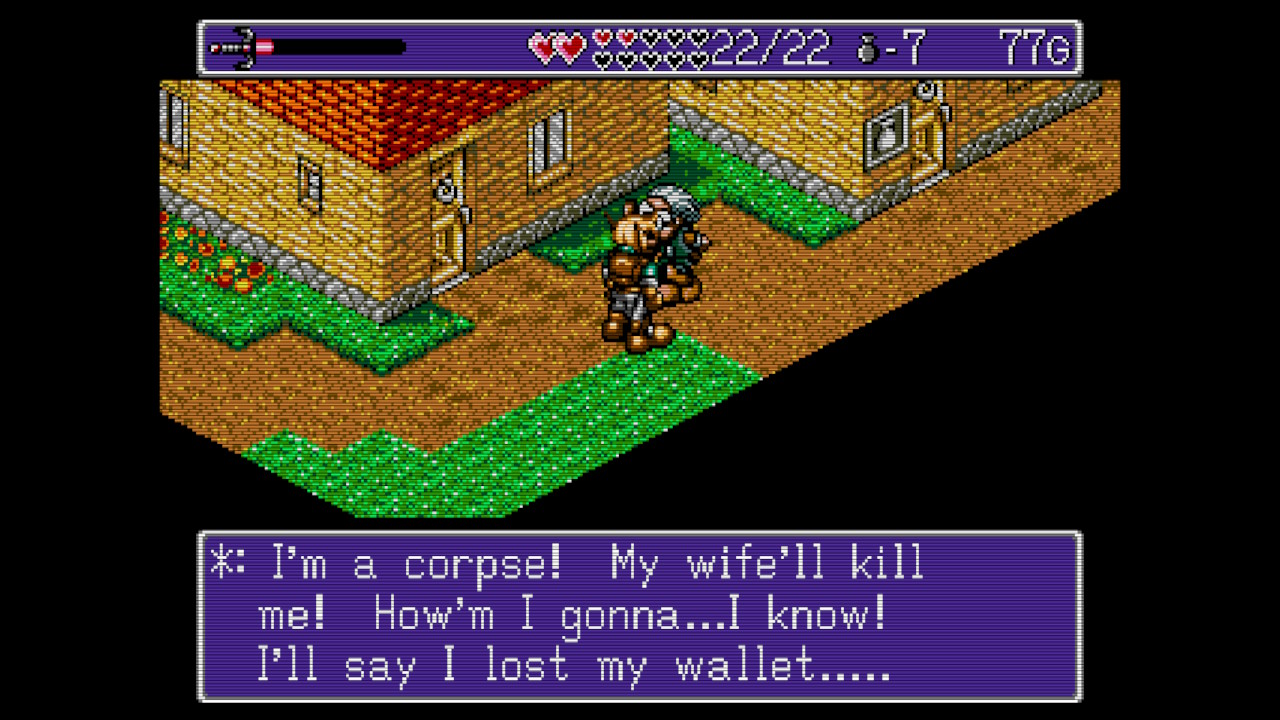

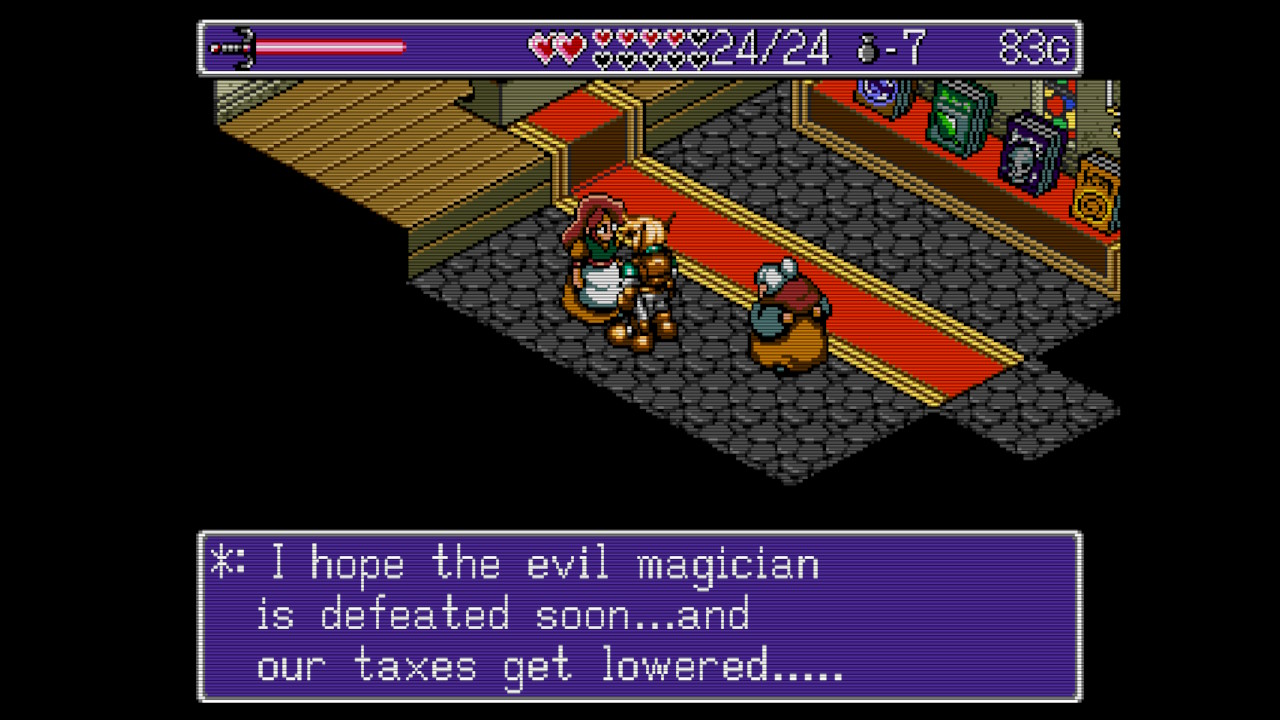

Whereas ALttP’s narrative has a sophisticated mythological air about it, Landstalker is rugged and rough. The main character, Nigel, is no Hero of Legend. He’s a thief/treasure hunter looking for a big score, and the journey begins with him learning about an ancient treasure from an eccentric fairy called Friday who accompanies us throughout the game and also develops an awkward crush on Nigel. There’s a playful cynicism to the way the game depicts people and their greed. This is especially evident when you reach the game’s human-populated big city, Mercator, which abounds with gambling, scams, sexual promiscuity and other forms of degeneracy all overseen by a corrupt dictatorial Duke, who serves as the main villain. Sure, the game tasks you with saving a princess at one point, but it’s played for laughs how much more motivated Nigel is by getting closer to finding the treasure jackpot than he is by the thought of becoming her hero. It’s also worth noting how much the game’s items are sanitized in the English localization, as the Japanese script carries these vulgar overtones. The English version’s Spellbook was originally a pornographic magazine, while the Pawn Ticket got changed from G-String.

Whereas ALttP’s controls are simple and intuitive, Landstalker‘s demand mastery and can be a struggle to grasp. Link’s feet lightly patter along the ground he treads when you press any of the directional buttons in ALttP, while Nigel’s movement feels weighty and unwieldy in comparison. In a way, the heaviness of the character’s movement complements the game’s more grounded and cynically “real” narrative tone. Instead of a simple top-down view, Landstalker uses an isometric perspective that requires you to input diagonal(!) directional inputs for Nigel to turn in the intended direction. Even the simple act of moving requires precise and deliberate input. This is compounded when the game starts throwing you into tight rooms containing numerous enemies you must avoid and position yourself around to swing your sword, or when it asks you to make jumps that require you to turn mid-air. If you’re the type of player who avoids games with tank controls at all costs because of the steep learning curve they demand, you might get frustrated with Landstalker.

On that note, it’s essential to highlight how much better the game’s movement will feel depending on your controller’s d-pad. For this review, I played the game on my Switch, mainly in handheld mode. Thankfully, my left joy-con is a replacement (courtesy of a drifting defect) with a proper d-pad because I wouldn’t wish that even my worst enemies play this game with the official joy-con’s perverse directional buttons. Landstalker’s movement is specifically designed to be conducted with a Genesis controller’s winged d-pad, which has those more clearly defined diagonal inputs. Even with my joy-con alternative or the Switch Pro Controller, hitting those hard diagonals felt tediously finicky at times. For the purposes of the review, I also tried the game on the Steam version of the Sega Genesis Classics collection with an Xbox controller. I’d recommend that as a preferable way of playing the game, unless you’re willing to invest in a compatible Genesis controller replica, a Sega Genesis Mini, or an actual Sega Genesis.

The emphasis on precise movement can be felt in the design of Landstalker’s overworld and dungeons. Like ALttP, the overworld is non-linear in its layout, but for the most part there’s an intended trajectory you’re meant to follow to progress. Each screen is more long than open, and usually contains several aggressive enemies you can fight or avoid using precise movements and by exploiting different levels of verticality. Unlike in ALttP, jumping is a critical part of the game’s vocabulary. Even when I was just trying to traverse from one town to another, the game never let me go on autopilot. I don’t want to have to make that comparison, but let’s just say I wouldn’t be surprised if Hidetaka Miyazaki was inspired by Landstalker’s uncompromising demand for its players’ full attention at all times. However, one of the game’s undeniable weak points is the visual monotony of its overworld. No matter how much of it you explore, you’ll be met mostly with the same grassy green and dirt brown assets.

Landstalker’s dungeons don’t have that much more visual variety (they’re almost all cavernous interiors), but they usually at least have a distinguishing color palette. With that said, the level design is outstandingly complex and varied. Nearly every room contains a distinct platforming, puzzle-solving, and/or combat challenge to overcome. As a whole, the dungeons are densely layered both horizontally and vertically. As I navigated through them, I had to keep a mental map of how spaces connect and overlap to ensure I remained on track. This is especially important when falling from a platform takes you back to a room you had passed through minutes ago.

And this is a key point. Because as much as Landstalker’s level designs are brilliant, they can also be quite punishing. It reminds me of the meme-y (but secretly brilliant) Getting Over It with Bennett Foddy, a game all about that sinking feeling of slightly botching your input and needing to suffer a sometimes-immense loss of progress as a result—only to require you to gather yourself and try it all over again. Landstalker’s claim to fame (or infamy, depending on who you ask) is its 3D-painting-like platforming segments. The game uses its 2D isometric perspective to intentionally make it a little ambiguous where a platform is relative to the other parts of the screen.

This requires you to study your surroundings carefully and judge where exactly you need to jump—or risk plummeting and losing a non-trivial amount of progress. Luckily, playing a modern port of the game means you can set your own quick saves to customize this unforgiving aspect of its design. Personally, I tried to play the game mostly honestly by only using quick saves when I became fed up with retrying a section. I found this to be a good balance that kept the gameplay tense and rewarding without letting it get too irritating.

Combat can also be quite challenging thanks to the precision required by the controls, but it doesn’t have to be punishing as long as you prepare yourself. Landstalker allows you to hold up to 9 Eke Eke fruit (the game’s primary healing item) at any time. They’re cheaply available at every store and you can find them in chests throughout the world or sometimes upon defeating enemies. Should you run out of life, Friday will automatically use an Eke Eke to revive Nigel, provided you have one on hand. Regardless of whether you choose fight or flight, you need to quickly think about how to move around your pursuers. The result is that every enemy you encounter results in an interesting gameplay situation that requires you to pay attention to their movements as well as the space around you. Unlike Link, Nigel does not have any tools beyond his sword (although you do get different swords with different powers), but this only makes Landstalker’s combat more focused and confident in its design.

This is all to say that, despite its abrasiveness, Landstalker is an ingeniously designed game and still a compelling experience today. If you like unusual Zelda-likes or punishing roguelikes, you may be more inclined to look favorably on the game’s quirks. It feels arbitrary assigning a score to Landstalker’s controls because they’re intentionally obtuse, but that obtuseness is part of what makes this game what it is. At times, I became frustrated with some of the obstacles and puzzles, but I also already feel compelled to replay the game. I’m confident that I’ll be able to handle the challenges this game throws at me better next time I play, and I’m sure overcoming them will feel incredibly rewarding.