Content Warning: Mentions of transphobic content.

RPGs set in and around schools are a trend these days, and with the popularity of Persona in particular, I can’t see them going anywhere. Lancarse and FuRyu (the tag-team behind Monark) hope some of their leads, who were behind seminal school RPG and Persona precursor, Shin Megami Tensei If…, can make the game stand out from the pack. They have succeeded in some respects, but the result is a very uneven experience that may have more lows than highs.

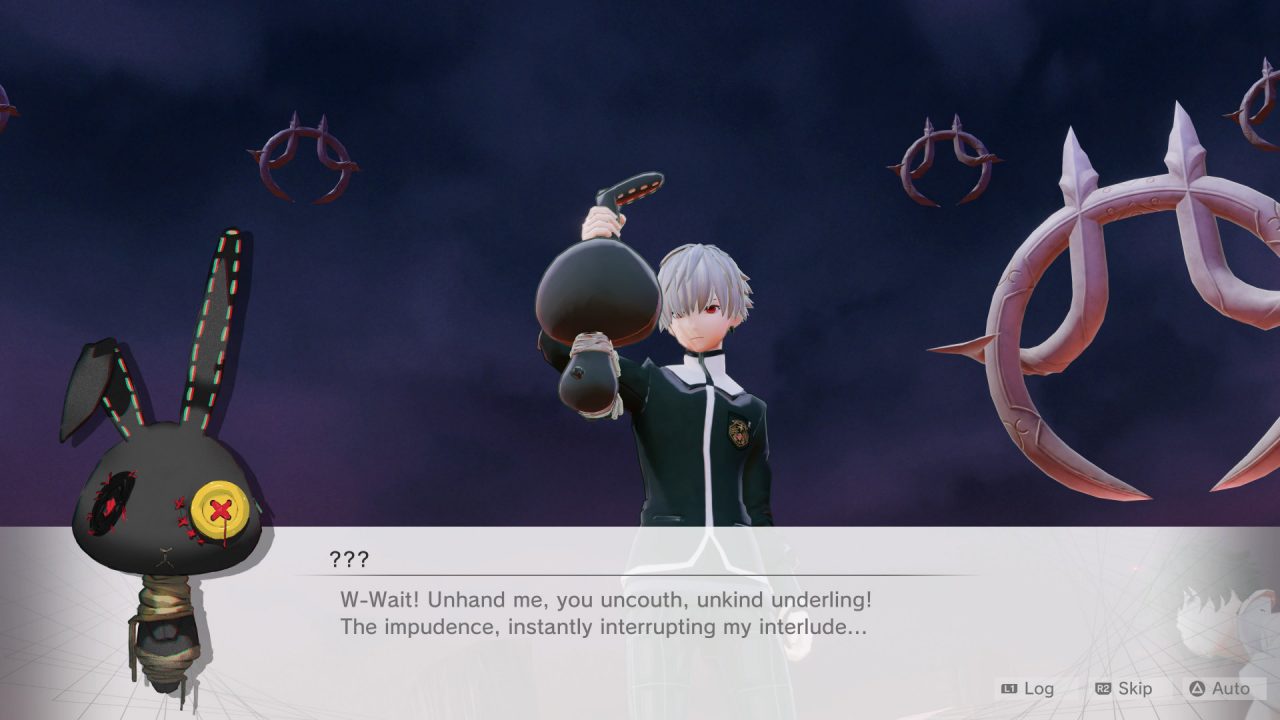

In Monark, players take on the role of an amnesiac highschooler on the worst possible day of high school. An impenetrable barrier has been erected around campus, a madness-inducing Mist spreads through the grounds, and strange powers have started manifesting amongst the students and staff. Naturally, all these phenomena lead to widespread murder and mayhem. To make matters worse, you and your sister are pulled into the mysterious Otherworld where Daemons dwell. There, you are granted the powers of a Pactbearer to protect your little sister.

Pactbearers are people with a strong Ego who have made a deal with a Daemon for the power to achieve their most fundamental wish. It turns out the other people who have gained powers are also Pactbearers, each tied to one of the seven deadly sins. Your powers, however, are linked to the concept of Vanity instead of one of the standard seven. I smell a mystery! To save the school, lift the barrier, and uncover some answers, you must shatter the other Pactbearer’s Ideals, breaking their Pacts and clearing the Mist, which is a consequence of them using their powers, known as Authorities.

While Monark makes use of many proper nouns, the core of its story is the students and how they handle this impossible situation. In particular, the four companions who can join you in battle develop during the course of the game and make many discoveries in understanding themselves and the world around them. Don’t go in expecting Persona-style bonding events or social link/confidant ranks, though. Most of the conversations and development happen within the main story. During these conversations, the dialogue choices you can make are… odd. The option you choose rarely matters, and the game reinforces this by often presenting a single option, multiple options that are basically the same, or multiple options that are the exact same. At times, choosing to say something even when it makes little sense for it to be a choice somehow makes me feel more immersed in the main character’s plight, like it’s me saying the line and not just the character. But at other times, it does the exact opposite and takes me right out of the story, usually when the only option feels like something my vision of the character wouldn’t say at all.

I don’t think it is controversial to say that games (both video and physical) tend to take an overly casual and broad definition when gamifying the concept of “madness,” and Monark is not an exception. However, Monark often does a surprisingly impressive job handling mental illness and its associated heavy subject matter in writing. For example, one of Monark’s villains is the Daemon-powered equivalent of a school shooter. You obtain context for what made him into the monster he is, but when you finally confront him, your current companion Kokoro dismantles all of his bullshit harshly and completely. Empathy does not have to mean forgiveness. This is a recurring theme of Monark: villains aren’t just beaten in battle, their ideals are also torn apart by you and your companions. Yet, Monark maintains that empathetic core, the understanding that people are made by their circumstances. Unfortunately, this only serves to make the game’s own bigotry more disappointing.

As you increase the aspects of your ego, you can obtain crystals scattered around the school that contain “alter-egos” of NPCs. These grant your party a permanent stat improvement and reveal a “secret” side to the NPC in their character profile. Most of these are interesting details that expand upon the NPC in question, but then there’s the one that is horrifically transphobic. Perrine’s character profile not only implies she is strange for being upset when deadnamed (and deadnames her in the process), but also follows up by misgendering her, suggesting she is “a boy pursuing feminine beauty.” I cannot dismiss such blatant transphobia. It made me feel sick to read and may have ended my playthrough had I not been reviewing the game. There are a few other questionable moments within Monark, but nothing sticks out as indefensible or blatant in the same way. I may have enjoyed much of my time with Monark, but how it treats Perrine was always on my mind.

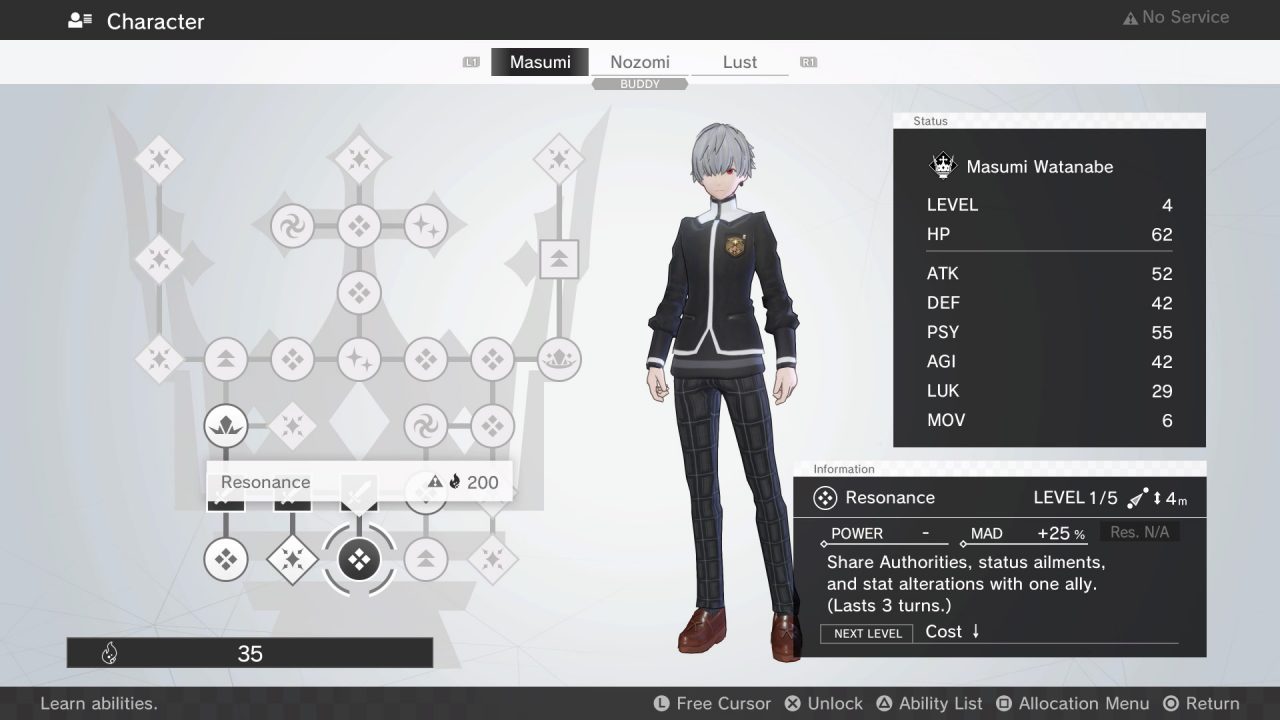

In practice, Monark’s combat system is that of a round-based SRPG. You may move a certain distance and perform a single action with each of your characters, and then the enemy does the same. Actions include performing Arts or Authorities or using items. You can always choose to wait in lieu of taking an action, which heals a bit of your HP in return. The main difference between Arts and Authorities is their cost. You spend HP to use Arts, while Authorities increase your Madness gauge by a fixed percentage. When a character’s Madness gauge hits 100% they enter Madness state, boosting their offensive stats, but causing them to attack whatever is closest to them, including allies. After three turns of Madness, a character is KO’d. Alternatively, a character who takes enough damage can enter an Awakened state, where their stats increase and they gain access to some Awakened-only moves.

Of course, because positioning is so essential, your units often can’t get into position to attack. Thankfully, Monark does some interesting things to break the turn-order mould and increase your tactical options. For example, one of your characters may move and defer to another friendly character who has already acted instead of taking an action, at the cost of increasing their Madness. You can manage some impressive maneuvers and win battles far more quickly through the smart use of deferring turns than you could otherwise.

Using the Vanity Authority also allows you to “resonate” with units on the battlefield, both friend and foe. You share status effects, buffs and debuffs, and access to Authorities when resonating with a unit. The latter leads to very exciting tactical options, as it allows many more uses of certain Authorities than you might normally expect. For example, my standard strategy in late-game battles is to resonate with my entire party, use a skill to massively boost my party’s psychic power, and then one-shot my enemies by using my most potent single-target damage Authority with every party member. Resonating also opens up a third “state” which a character can enter, Enlightened. If the main character is Awakened and resonates with a character in the Madness state, then all resonating characters become Enlightened, receiving a huge power boost for the duration.

Spirit, known in-universe as the “currency of the soul,” is obtained upon victory in combat. The better you do in battle, the more you earn. It is used to learn new skills, upgrade existing ones, and buy items. Whenever you learn or upgrade a skill on a character, their level also rises incrementally, improving their stats.

Monark has very few mandatory battles in which to earn Spirit. So, to keep up with enemy levels, you must choose to undertake optional battles by calling phone numbers you find in memos found across campus. This feels like a blessing early on; you control the game’s pace and it is easy to keep up with enemies. Unfortunately, as skills start to cost more and the size of the battle party increases, undertaking a pace-destroying number of optional battles at regular intervals becomes the norm to keep up. Personally, I would have preferred random or symbol encounters if it meant a more even pace.

This messy pacing only gets worse the deeper you delve into the game. I won’t dance around it; the latter half of Monark is remarkably repetitive. I can appreciate what it is trying to do and what it’s inspired by, but it clearly does not understand why the progression in those games that inspired it worked. To say anything more would spoil the story, so suffice it to say, the bulk of time in the second act is grinding battles just to keep up with your enemies. While this becomes quite a bit quicker once you figure out the right strategies and have access to appropriately levelled Fertile Grounds (battles which offer bonus Spirit upon clearing), it never ceases to be a chore. I should also mention there are a couple puzzles in the game that are quite abstract and may require a guide to solve, another pace-killer.

Outside of the spectacularly animated and framed opening, Monark is not exactly visually impressive. The art style is pleasing and the character designs are striking, but textures are plain and the character models themselves are stiff and awkwardly animated. In comparison to its visuals, Monark’s audio stands out more. The majority of its soundtrack is just fine, and not particularly memorable. It serves its purpose well. However, the game’s opening and each unique boss battle have genuinely incredible vocal tracks made in collaboration with several popular virtual singers like KAF and CIEL. You can listen to any song you have heard in-game from the menu, and I find myself putting on the vocal tracks and just listening through them surprisingly often.

Monark isn’t a great game. I am not even sure I would call it a good one, but if it weren’t for the transphobia and atrocious pacing, I would likely be enthusiastically recommending it to the right sort of player. There is an earnest quality to its themes, characters and stories paired with an inventiveness to its combat. These qualities build a solid foundation a follow-up title could improve into something truly special. As is, if you have read my review, watched the trailers, played the demo, and still have interest in playing Monark, there is probably a good chance you would find some joy in playing it. For anyone else, you are likely best off waiting for the next Persona or a Monark 2.

Editor’s Note: Following publication of our review, representatives from NIS America reached out to us to clarify the writer’s intent for how Perrine was represented. As RPGFan does not alter reviews based on publisher’s requests, none of the originally published review has been changed. To be clear, NISA made no such requests for edits, in any case, but we agreed to share their statement here to be transparent about the discussion:

“…while we were made aware of the implications of that content, no harm was meant by it, and that we uphold acceptance as one of our core values and do not condone discrimination or bigotry in any form.“