Storytelling in video games has cemented itself as a unique medium for art. Whether you’re in for laughs, tears, or a philosophical “hmm,” video games have you covered with high-quality options. One genre that I am not sure has had enough attention is “slice of life,” a voyeuristic peek into a section of a person’s or people’s normal lives. Mr. Saitou has the same easy-breezy feeling, and with a two-hour runtime, it certainly is a slice.

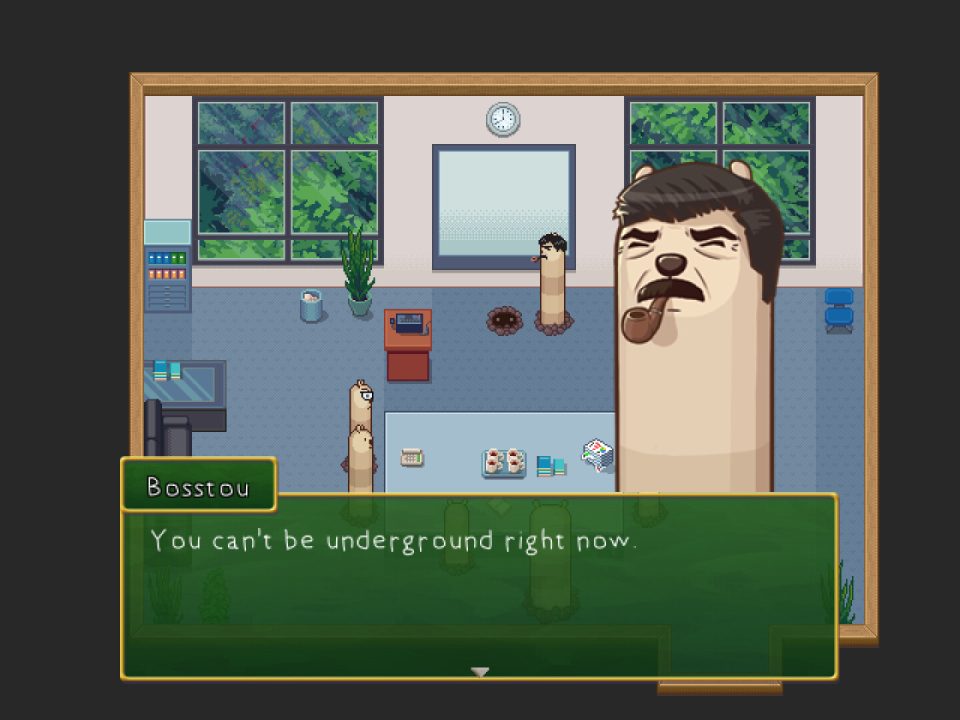

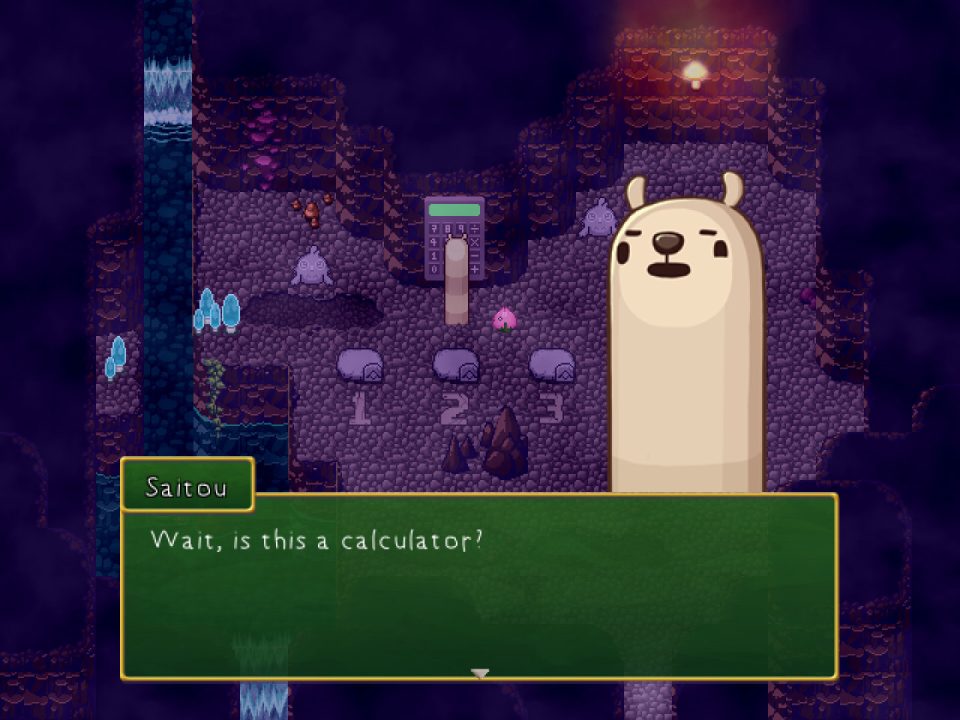

In Mr. Saitou, we get a glimpse into the exhausting life that lead protagonist, Mr. Saitou, leads as a salaryworker. He toils away in front of a computer screen for all hours, goes out for a meal he’s too tired to consume, and stumbles home in a tired, drunken stupor. Next thing we know, he’s collapsed and we’re in a hospital. After meeting a young boy in his hospital room, he learns about a fictional character the kid has drawn named Mr. Saitou: a llamaworm who works an important job making buttons for the tunnels that other llamaworms traverse.

Most of the game takes place in this fictional world, with Mr. Saitou starring in llamaworm form. Throughout the adventure, we get a surface-level (ha) understanding of how llamaworms exist, along with other denizens and species folks might recognize from Rakuen. Officially, this is considered a “Rakuen universe” game. This world is a lot like ours, except inhabited by all manner of fictional creatures. Minimori, bulbous and cute bug-eyed birds, are a presumably terrifying menace Mr. Saitou, in particular, is afraid of. This world has its celebrities and academics, but nothing is fleshed out too fully; after all, this is a two-hour game.

People familiar with Japanese culture will find frequent references to our friends in the East with work culture, the physical layout of the offices, convenience stores, and so on. While I don’t think these references add anything of substance, they provide a sense of place and comparability to our real world. As such, Mr. Saitou is bogged down with work expectations, feeling frequent pressure to perform and get ahead. While certainly not stated outright, the world of the llamaworms seems to be a cute metaphor for what many in reality go through, particularly Mr. Saitou.

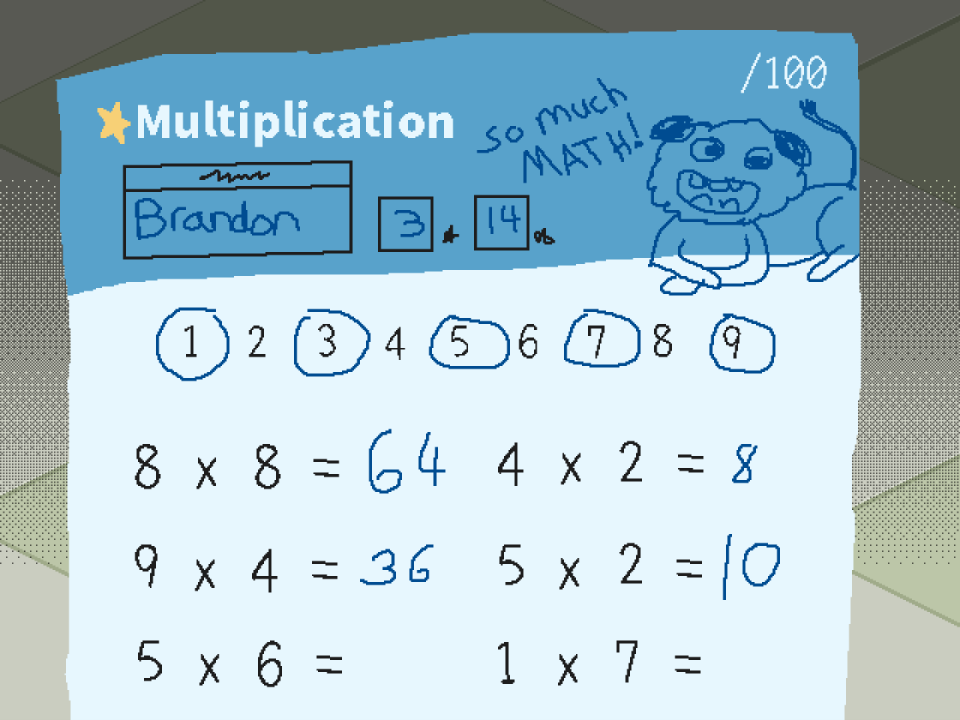

Much of the game requires Mr. Saitou to complete fetch quests or tasks for various people, which is a thinly veiled attempt to get the player to walk around and talk to everyone. This is fine because the actual task isn’t time-consuming and we’re here to play the game, which I interpret as getting to know the world and its people. Clicking on objects in the environment sometimes yields mildly amusing references to math, the human condition, or a concrete and plain description, such as stating that a bucket is empty. Characters can be wacky and humorous in a child-like sort of way, though some are surprisingly flat.

Unfortunately, I can’t say anything really happens in Mr. Saitou. We do things, meet people, and complete tasks assigned to us, but none of it feels as if it has any purpose or meaning. The central plot isn’t outwardly stated, which can work, but the theme the game presents with mild subtlety at the end does little to justify the hum-drum of the two-hour investment. I want to say I like this game and find it engaging, moving, or thoughtful, but I honestly didn’t feel any of that. Mr. Saitou has heart and has something to say, but I spent most of the game asking myself: why am I doing any of this?

This is why I think this presents itself as a slice-of-life sort of game. Part of the style of a slice-of-life story is that nothing of magnitude happens; we are here to witness the ordinary in hopes that we can relate to it. The stakes are generally low, and a calm atmosphere pervades the storytelling. Games need more of this as much as movies and TV shows need it, and I’m here to say I appreciate this genre. Does it entertain and hit the mark with Mr. Saitou? Again, I wish I could say it does.

The ending helps a lot. While not all that surprising or elaborate, the timing and delivery hit a satisfying note, which is a relief to me. I love Shigihara’s work, whether it’s composition, singing, or the masterful creation that is Rakuen, so I had hoped this would stick the landing. In a sense it does, but it doesn’t entirely justify the journey.

Speaking of composition, Mr. Saitou’s music complements its chill, low-stakes feel with simple, light-hearted tunes. Some references to Rakuen are clear for those familiar, which made me smile. While not all of the songs are stellar, a few charm and caused me to stop and sit back to just listen. Visually, this feels like a style we might expect from To the Moon and Rakuen, that being RPGMaker quality. The spritework is excellent, but this look won’t resonate with everyone. I cracked a smile quite a few times with comically delivered facial expressions and pauses. Players don’t have much agency besides walking around, talking to people, checking objects, or maybe pulling up the menu to save so the controls don’t get in the way of gameplay.

I don’t doubt that some folks are going to fall in love with the breezy vibes Mr. Saitou delivers; not every game needs a gigantic demon boss or world-ending evil. For what Mr. Saitou appears to be trying to do, though, I can’t say the satisfying ending justifies the journey. If more of the conversations or relationships I had with the characters had more texture, I would say otherwise, but I spent too much time having directionless interactions. If nothing else, Mr. Saitou has heart and something to say, and if that’s worth two hours of your time, you may be the audience.