Mario is gaming’s most recognizable character, and that has been to the psychedelic plumber’s detriment in many ways over the past two decades.

Ever since the Mushroom Kingdom’s aesthetic homogenization that took shape in the mid-2000s, fans have been clamoring for the weird side of the franchise to make its grand return. Nowhere has this been more noticeable than the Paper Mario series, which swiftly saw its many unique character designs washed away in a sea of generic Toads and Goombas. By this same measure, the series has increasingly strayed from its turn-based RPG roots, leaving that lineage to the now-dormant Mario & Luigi series.

Because of this, Paper Mario: The Thousand-Year Door is endlessly held up as the ideal for what Mario RPG fans want to see from Nintendo. Compared to other GameCube re-releases on Switch like Pikmin 1+2 and Metroid Prime Remastered, The Thousand-Year Door’s one-for-one remake feels more significant, as if Nintendo is finally responding to the desires of the paper plumber’s fanbase. Plus, the game was stranded on GameCube hardware, making it inaccessible even for Mario RPG enthusiasts. This includes me.

I’m delighted to say that the wait paid off. Paper Mario: The Thousand-Year Door serves up some of Nintendo’s best-ever character writing, as well as a battle system that fleshes out nearly every aspect of the Mario RPG combat formula. However, while the positives shine through, some creases keep the game from reaching its full potential.

The vibrant world and characters are the stars in The Thousand-Year Door’s show. This is not your typical squeaky-clean, family-friendly Nintendo fare. Even with the foreknowledge that it was in the game, I was still shocked when one of the first things I saw was a noose in the dead center of the seedy hub town’s plaza. While this is probably the most extreme example of content that usually wouldn’t pass muster at the Big N, it immediately indicates that Mario’s gonna walk out of this one with grime on his boots. Around every turn are criminals, mobsters, and other ne’er-de-wells who make Bowser look almost friendly by comparison. However, this is juxtaposed with irreverent wit that playfully dips into sardonic, fourth-wall-breaking waters. While this style of humor has been done to death, somehow The Thousand-Year Door’s writers managed to consistently land punchlines I didn’t see coming.

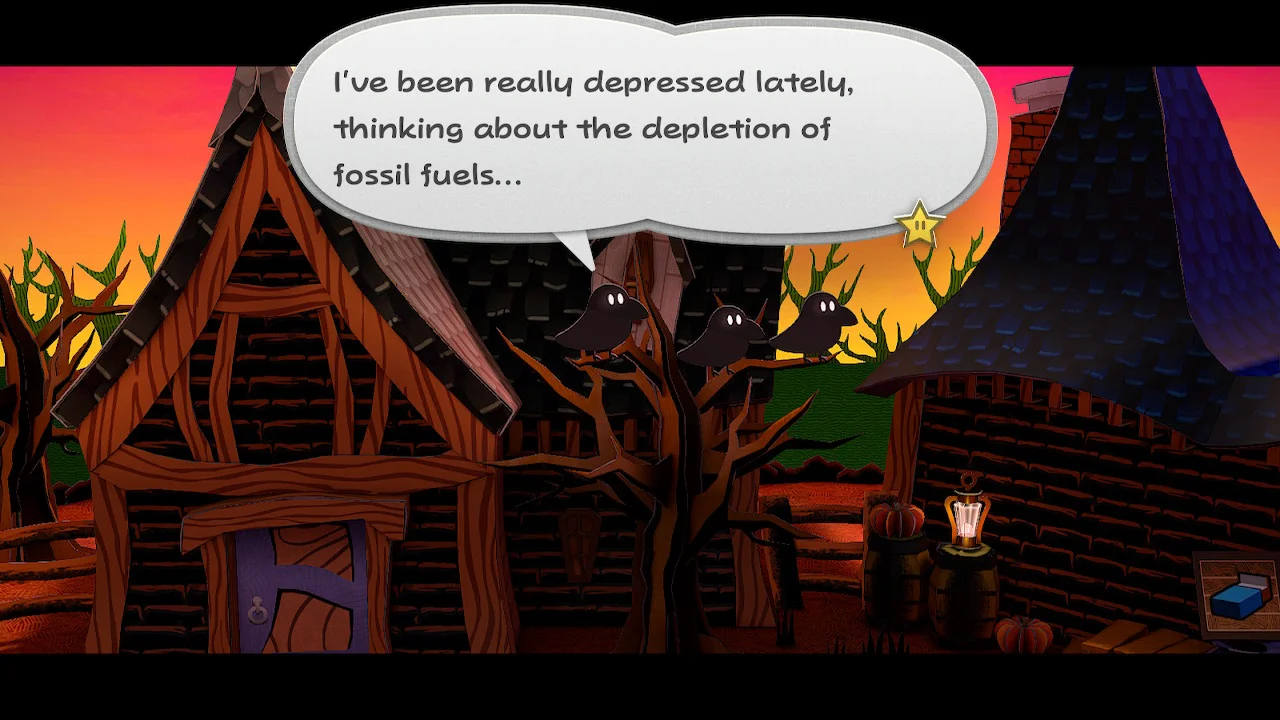

Also critical to this style is knowing when to reign in the jokes, something the game also nails. Key plot beats are rarely undermined in the name of a joke and the game treats sensitive subject matter such as gender identity and trauma with delicacy. Heck, there are moments when the game flat-out discusses real-world issues, which (unfortunately) remain relevant to this day. Moments like these are kept to optional character interactions, which only furthered my desire to talk to everyone.

I seriously couldn’t get enough of these characters. Of particular note is Mario’s main partner Goombella, a sassy Goomba student who has individualized snarky dialogue about every single NPC and enemy in the game. Even mainstays like Peach, Bowser, and Luigi have arcs in this game that transcend their usual roles. However, I found the main villain, Grodus, and his X-Nauts underwhelming because they never felt particularly threatening. The stakes typically felt higher with the small-time antagonists of each arc and lower if the overarching villains happened to get involved.

By this same measure, while I found the overarching storyline adequate, the sub-stories that make up most of the game’s runtime kept me glued to my Switch. These misadventures include competing in front of a raucous audience in a wrestling ring for a prize belt, solving crimes with a questionable penguin detective on a luxury train, saving a ghostly town whose inhabitants turn into pigs, and so much more. It plays out like a television procedural season where each standalone episode has enough plot twists and shakeups to fill the whole season of a serial. These stories are where The Thousand-Year Door made a name for itself and the main reason why you should play it.

Actually playing through these stories is a bit more of a mixed bag. Most areas are presented as side-scrolling levels, complementing enemy combat with platforming and puzzles. Add to this a plethora of discoverable secrets and some essentially linear corridors become engaging mazes. Navigating them involves invoking Mario’s partners’ abilities, and you can swap between them using a nifty wheel. You need to regularly use your full arsenal to maneuver through traps and environmental hazards, meaning the entire party remains relevant until the journey ends. I appreciated that a handful of puzzles required some trial and error of partner abilities to solve, though don’t expect anything too challenging here. Similarly, while platforming in Mario RPGs is a tried-and-true part of the formula, the side-scrolling perspective lends The Thousand-Year Door a sense of authenticity to the mainline platformers.

This authenticity is a catch-22, as comparisons to games renowned for their character controls aren’t flattering. There’s an inherent decrease in fluidity and responsiveness that comes from the game’s 30 FPS cap, down from the original’s 60 FPS. Moving Mario sometimes feels like wading through mud, and a mix of input delay and movement rigidity resulted in missed jumps that didn’t feel like my fault. Given that you lose health for these missteps, it creates pangs of frustration around a part of the game that should feel ancillary. While I could hurl similar complaints about touchy platforming at Super Mario RPG: The Legend of the Seven Stars, that game gets away with its jank due to its non-traditional perspective. The Thousand-Year Door would’ve done well to understand that if you come for the classic Mario platformers, you better not miss.

However, there’s a more fundamental issue with the game’s level design: backtracking. Most side stories will have you repeating your trek through the same handful of screens multiple times with no variation. I can excuse the couple of times this tedium is played for jokes, but it otherwise feels like artificial padding on an already lengthy game (by Mario RPG standards). Even the most interesting levels become less so when continuously forced through them. The problem is accentuated by side-quests that require you to return to dungeons, especially since you can only accept one at a time, forcing trips back and forth from the hub town after completing each one. A few of these unlock minigames and even one of Mario’s partners, so you’re missing out if you skip them altogether. Despite all of this and their bare-minimum fetch quest nature, the interactions with various townsfolk they offer provide fantastic worldbuilding, which is a reward in its own right.

Combat is what you expect from a Mario RPG, but expanded. By pressing “A” at the right moment, you can power up attacks or reduce damage from enemies. Additionally, pressing “B” within a tighter window will completely negate an enemy’s damage and—if the attack includes physical contact—hit them back for a point of damage. These superguards are difficult to pull off and punishing if failed but, in greater measure, extremely satisfying when nailed. This additional defensive option enhances the fun of learning enemy attack patterns, and there’s exceptional enemy variety throughout the game to keep you constantly learning. Even reskins of enemies have different properties that alter how you approach them or how they approach you.

The partner system, the game’s stand-in for a traditional party, is essential to combat. Mario can have any one of his newfound friends join him in battle at any time with each fulfilling a different role. Picking the right partner for the job can make the difference between a tough fight and wiping the floor with your foes. They can also swap positions with Mario to act as tanks, as only the man in red’s death signals a game over. While each individual partner is limited in their skillset, the interplay between these systems leaves room for a lot of strategizing. Unfortunately, the partner-swapping mechanic fails to capitalize on that potential. To explain this, I need to talk about Goombella’s tattle.

Like many RPGs, you can assess enemies to learn their weak points. Goombella is relegated to this role in The Thousand-Year Door through her tattle skill. It’s all but essential to tattle every enemy because doing so not only reveals their stats and weaknesses (alongside some wonderfully snide commentary) but also displays their health bar for every subsequent encounter. To make sure you achieve this, you need to keep Goombella as your partner much of the time. The kicker is that swapping out a partner in battle takes up either the partner’s or Mario’s turn, which means if you’re using Goombella a majority of the time, you rarely use other party members even if they’re a better fit for the fight. There’s a disincentive to swap between party members when it should be incentivized. Sure, I might swap to a physical attacker best suited for a formation of enemies, but support characters become useless because the battle’s progressed by the time they’re set up to aid Mario. While I fathom that a quick swap in battle could lead to abusing the health of partners kamikaze style, the game is never difficult enough to require that, and so much more is lost when it feels like a burden to utilize my full party.

There’s still plenty of depth in other systems, though. The badge system allows Mario to equip permanent game-changing boosters. Badges provide a grab-bag of effects, including access to special attacks, regenerating health and flower points, and rule-changers like allowing Mario to use jump abilities on spiked enemies. The customization this allows is far more interesting than your typical equipment systems given that just about any badge is viable and their impact is immediately observable in battle. To the system’s credit, it never feels overwhelming despite offering so much choice.

Combat locations are even critical: you do battle on a stage, complete with standee environments and a captive audience. This enables random events like equipment falling onto enemies and audience members throwing items. There’s always something kooky going on that’s shaking up battles, provided you don’t stomp through them on your first turn. When commotion breaks out, it results in the most entertaining turn-based combat in a Mario game to date; watching a Shy Guy rush the stage to cause mayhem never gets old. If it weren’t for the shortcomings of partner swapping, I’d probably declare this an all-time great battle system, but instead I’ll settle for a cut above your typical Mario RPG.

We’ve yet to talk about two of the big selling points of this remake: its visual presentation and music. This newly orchestrated soundtrack is extremely well produced and sounds great on both modern speakers and headphones. Of particular note is how the battle theme changes for each area, something I honestly wish every JRPG did. While there aren’t many earworms on the level of Super Mario RPG‘s, the soundscape provided perfectly suits the game. There’s some truly wacky stuff here that helps breathe life into the creatures inhabiting this corner of Marioland. For players who prefer the GameCube soundtrack, an option to swap is available early in the game.

Lastly, I can’t praise the visual presentation enough. The commitment to creating nearly every aspect of the world out of paper is jaw-dropping, even with an abundance of Paper Mario games now in existence. It’s the little details like the imperfections in various bits of papercraft to unmissable spectacles like the entire screen crumpling away for stage transitions. Add to this that Mario interacts with his paper world through his own paper-folding powers and you’re never left questioning, “But why paper?” It just works. While the typical lack of anti-aliasing in Nintendo titles and a lack of smoothness in some moments due to the 30 FPS cap brings the visuals down a tad, it’s not noticeable when the art direction makes magic happen before your eyes. Also, kudos to the team for recreating the game’s assets, as such a task is no easy feat. The fact they had people thinking this remake was a remaster upon its reveal speaks volumes to their skill.

From showtime ‘til curtain call, Paper Mario: The Thousand-Year Door is an unpredictable adventure that kept me hooked. If you’ve been interested in trying this game like I was, you’re probably not going to be disappointed. Wrinkles like the excessive backtracking and restrictive partner swapping in combat hold back the game from its true potential, but its witty writing and arresting art direction make this a singular entry in Nintendo’s RPG lineup. Hopefully, Nintendo’s taking note and course corrects for their next Paper Mario entry.