Ah, the ’70s. The world was disco dancing, trying on bell-bottoms and embroiled in the Cold War. Along with other major world powers, Japan was also exploring nuclear technology, but to provide energy to its citizens rather than for bombs. The 1970s is also when Undernauts: Labyrinth of Yomi begins, two decades after weird, massive structures first appeared in several cities across the world.

Inside the labyrinthine structures, miners discovered hordes of riches. The professionals who undertook this venture became known as undernauts, but the structures held more than wealth. Explorers also found bizarre, violent monsters, which they dubbed Yomians. Apparently lacking any reasonable sense for danger, the undernauts were undeterred and continued to operate. And if it sounds like this venture is rife for disaster, well, that’s where you come in as an undernaut trying to make a living yourself. Once everything predictably goes wrong inside Tokyo’s structure, it’s up to you to figure out how to get your team out to safety.

The strange atmosphere of Undernauts: Labyrinth of Yomi is a sausage of Japanese cultural norms and fears. Your crew relies heavily on nuclear energy and the company you’re working under steeps itself in proper work culture. Your supervisor evokes these concepts in his attire alone; weapons and armor cover his body, but his salaryman outfit still peeks out from underneath. There’s underlying humor about your company’s uber-professional vibe. For example, your portable radio picks up broadcasts offering safety tips for enduring the extreme, monster-ridden environment, and these are amusingly reminiscent of work memos. You use nuclear power to restore your party members (doesn’t sound too healthy) and to melt down your excess items to create new ones out of the waste. But the realistic, modern world collides with more of a dark fantasy setting inside the structure. There’s a surprisingly deep lore to all of this. Japanese society reveres undernauts as mythical heroes — comparable to professional wrestlers or Ultraman — and even creates trading cards based on them. The game throws in some generic anime horror, too. You never want to run across someone referred to as the Girl in Red.

Undernauts: Labyrinth of Yomi, a first-person, old-school dungeon crawler, fashions itself as a slight throwback to the earliest RPGs. We remember early RPGs more for their ridiculous difficulty than for their stories. Completing them is akin to a badge of honor and achievement for the bravest. That old-school mentality shapes not only gameplay in Undernauts: Labyrinth of Yomi, but also its minimalist narrative. It begins as an almost isekai story about survival and exploration in a strange and brutal world. Eventually, it shifts into something more meta, like peering into the mind of a geeky sociopath who might design such torturous games. The story nearly reaches self-parody at a few points, almost winking at you, fully aware of its limitations in design and recycled monsters and environments. Though this type of game usually focuses on combat, this one boasts a decent story overall, though that narrative stretches itself a little too thin over a lengthy playtime.

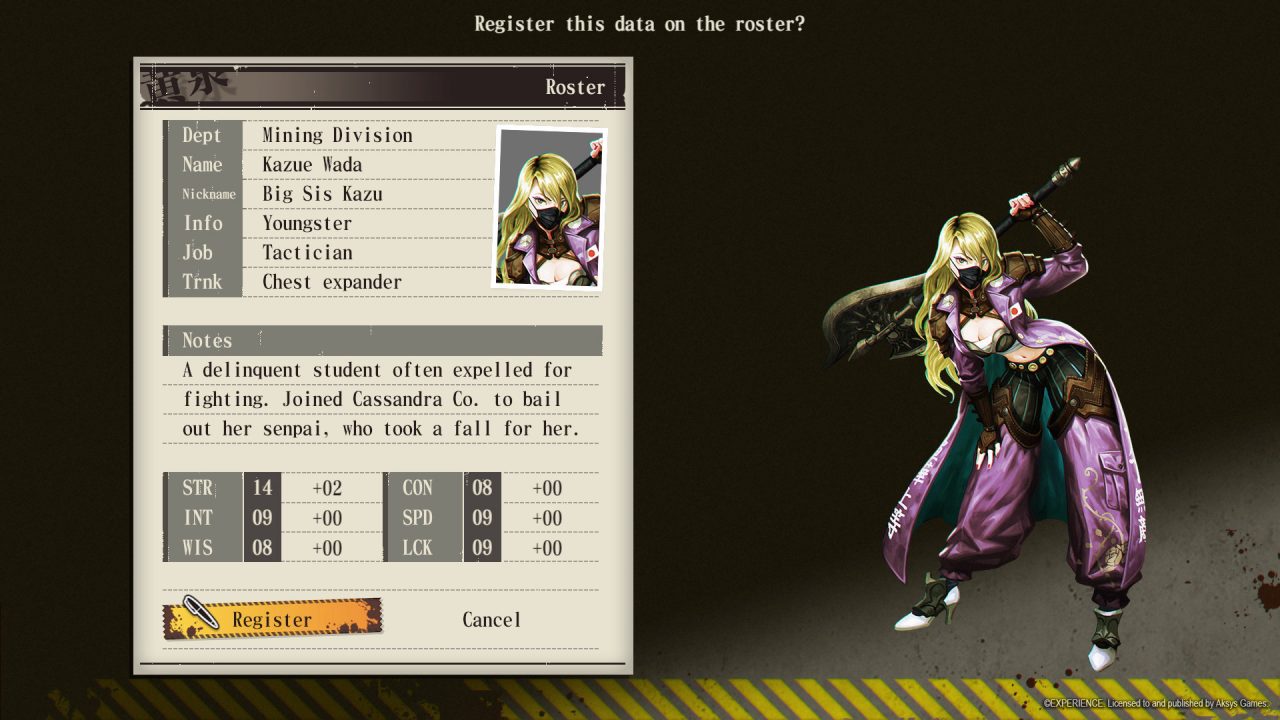

In typical dungeon crawler fashion, you explore the dark, dank world of Undernauts: Labyrinth of Yomi one square at a time and engage enemies in traditional, turn-based combat. You must build out a party of six characters from eight jobs, five of which are melee-based. While their titles sound diverse, ranging from tactician to ninja, you won’t notice the nuances between the melee classes until much later in the game. While you determine the final party configuration with three characters in front and three in the back, it’s common practice to have three melee fighters out front and hide the squishier ranged, magic and healing combatants at the rear. You can create as many characters as you want, though I never saw the need to make more than the six I started with because you can respec your characters nearly completely. You can also promote your characters to gain access to more powerful skills, though promotion items are rare.

The game pushed me to make my most thought-provoking decisions while I was preparing for combat. Some equipment is more or less effective against specific types of monsters, and the difference is surprisingly drastic, so there’s more to consider than sheer attack value when outfitting your characters. As a result, procuring better loot is an important part of making progress. While you can upgrade the equipment you have, it’s costly to do so, and obtaining better items through defeating enemies is generally a quicker way to improve your party. Accuracy and evasion also play a more significant role than in other RPGs. Though combat is mechanically solid, the ideas are basic and not particularly engaging. There’s little interplay between the jobs, so your tactics in battle mostly consist of hammering enemies with your strongest attacks.

There is one impressive, innovative addition to combat, and that’s the Switch Boost. You start every battle with three switches, each of which grants your entire party a bonus for one turn. However, you can only use any of them once before you need to recharge, which takes a turn. Overcharge lets your characters use skills without depleting MP, Duracharge halves damage you take from enemies, and Neurocharge gives you extra XP and treasure if you finish off the last enemy while it’s active. So you have to balance risk versus reward and timing as you try to maximize your gains from each battle, hitting Neurocharge at the optimal time. And in difficult fights, utilizing Duracharge at the right time can be a lifesaver. Undernauts: Labyrinth of Yomi is a pretty combat-heavy game, and it becomes tedious at times. Switch Boost adds something extra to consider, but it doesn’t always alleviate the monotony of standard battles. Giving players bonuses to manage seems like a great direction for JRPG battle systems to evolve in, but the concept has much more potential than is realized in this game.

Exploration is the other main component of traditional dungeon crawlers aside from combat. One of the undernauts’ basic rules is to explore every space edge to edge, meaning you should be sure to cover every square. If you’re ever unsure of what to do next, there’s a good chance you haven’t explored the entire space in a given level. As in other modern dungeon crawlers, the game provides you with a map instead of forcing you to draw your own with pen and paper. Whereas games like Etrian Odyssey leave it up to you to mark up your in-game map with points of interest, Undernauts: Labyrinth of Yomi automatically fills it in for you. Not needing to manually take notes saved me a ton of time, but there’s no option to add your own notes to the map. You often seek out hidden passageways to proceed, so it would have been helpful for me to be able to mark off areas I’d already explored. That way, I could have spent less time retreading old ground while figuring out how to advance the game.

The exploration-combat balance has some issues, too. You participate in random battles, but not all that often. Instead, symbols on certain squares represent the most common encounters you face so you can explore pretty freely and fight at your own pace. However, with some potentially severe difficulty spikes, you need to spend hours upon hours to overcome them. Given that you need to dedicate 100-plus hours to finish the game, this is an exceptionally tall order. Undernauts: Labyrinth of Yomi does give you streamlined means to grind, so you don’t have to wander all over maps in search of enemies, but combat isn’t engaging enough to keep the grind enjoyable.

In addition, there are fates worse than dying in battle. You almost never truly die, reawakening back at base camp if enemies defeat you. Resurrection comes with a cost, though. Specifically, it costs argen (your currency) to revive party members, and you don’t have any items or spells to bring them back while in the field. The game’s autosave becomes both a blessing and a curse because you can’t save manually. Not having enough argen to resuscitate your comrades after enemies wipe them out is the greatest terror the game has to offer.

Visually, characters are impressive, and you have dozens of spiffy avatars to pick from for your fighters. Monsters look great, too. The designers often appeared to chose two animals or objects at random to mash together into an unholy combination, such as frogdog or dragontank. If you really like any of the monsters, you’re in luck because you are likely to see them again but with different color schemes or more limbs or tentacles growing out of odd places to denote stronger variations. And though they look cool, I rarely thought the monsters looked as frightening or intimidating as the game’s horror vibes try to make them out to be. The environments, however, are somewhat bare. Some are more intriguing than others, but immediately upon entering a new area, you know what to expect for the next few hours. If you’re like me and usually stare more at the in-display map than the main screen in games, at least you know you’re not missing anything here.

The game’s music is a fascinating mix, from sludgy jazz and jazzy orchestral arrangements to vocal-heavy boss fight songs, including one that evokes “Carmina Burana.” It’s a bold choice to have a woodwind instrument lead the general battle tunes. And “Namennayo,” the undernauts’ poppy theme song, is cheesy fun.

Ultimately, Undernauts: Labyrinth of Yomi is fine for what it is. Though exploration and combat primarily define dungeon crawlers, the fighting in this game isn’t interesting enough to justify the grinding necessary to progress. While I was curious to see the conclusion, both story and combat would have been more effective in a game about 40-50 hours shorter. Undernauts: Labyrinth of Yomi buries its treasures in deep depths, and some won’t find them worth digging for.