Fallout 3 was a landmark game. It emerged at a time when high fantasy primarily represented 3D open-world roleplaying games and shifted the genre’s possibilities. There had been some alternative settings at the time, but Bioshock euphoria dominated the cultural zeitgeist. In 2008, large, first-person game worlds with a distinct level of verisimilitude existed in the domains of a select few: Bethesda’s own Elder Scrolls series, smaller studio efforts like the Gothic series, or older offerings like Deus Ex. Even these compatriots failed to match the level of graphical fidelity and thematic intensity depicted in the Wasteland of Fallout 3.

It also helped that players had previously explored and fleshed out the Fallout world in the isometric CRPG genre through its predecessors. Fallout 3’s older siblings succeeded in creating a fascinating game world but were limited to PC users and a small genre niche. With the coming of the PS3/Xbox360, millions of potential new players were on hand to bathe in the Fallout glow and bring the franchise to the mainstream in the process.

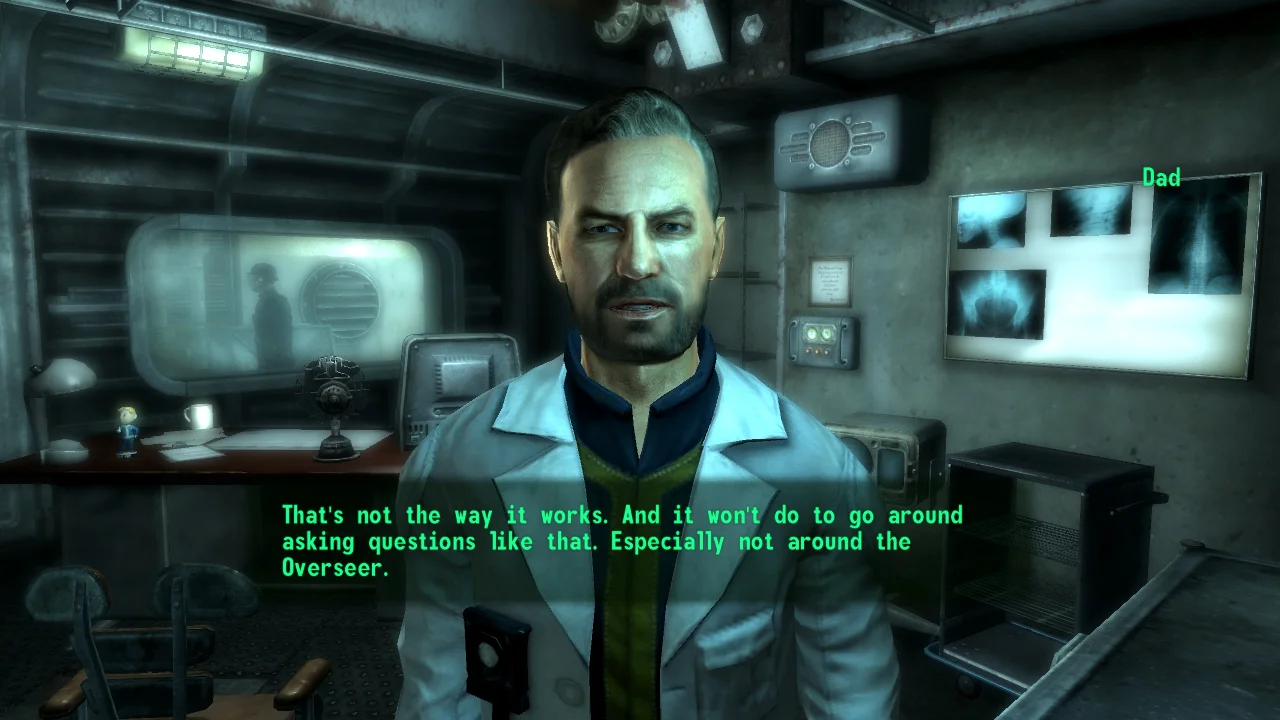

Cleverly, the game starts small—you chart the main character’s life from their birth in an underground Vault on the east coast of the USA, many years on (as it is revealed) from a nuclear war that shattered the world. The Vault was designed to save the best and brightest of the population and developed its own social order over the many years of seclusion. After a kerfuffle involving the player’s father, we are soon on our way through the Vault and moving toward a destiny amongst the Capital Wasteland.

Most of us know the story beats and locations and are familiar with the journey to discover a father’s ideas and heritage. It would be wrong to call the narrative exceptional. Yet it is enough to have us following plot breadcrumbs from one place to another, drawing us toward the first humanitarian gatherings that form the world’s fabric. Megaton, Arefu, GNR Station: places that now resonate more with the memory of what we did with (and in them) than how they fitted into the main story. The characters, places, and missions that take place as a sideways step have always been the main draw and led to the most emergent storytelling. Who hasn’t accidentally shot up a traveling merchant during a Raider firefight, forever removing them from the world? Or seen a horde of giant ants savage civilian characters (and each other)? Or just plain wanted to deprive Megaton of its sheriff? In these moments, the game draws upon its older parents the most through the choices it offers our characters or that we offer them.

And, like the earlier installments, our character is our own. The SPECIAL system returns in an adjusted format, with skills and perks to further define what our avatar can do well. Whilst combat and firearm skills are simplistic (even a noob can point and shoot most any weapon in the game), the social and technical skills gate off certain options in the world, forcing players to consider whether a stealth approach is their means, rather than opening locks or hacking computers. It’s a solid system, and given that open-world RPGs of today still use a similar approach, it’s a design that has stood the test of time, with a few variations. In fact, the line of connectivity from Fallout 3 to Starfield (16 years!) is clear to see. It’s remarkable to feel that the design at Bethesda remained static and locked during that period.

The downside is that it becomes a zero-sum equation in 2024. Whilst this was unique in 2008, we are now so used to skill variants that we almost meta the approach without thinking. On the original release, it was cool to realize that a character could be rubbish at picking a lock but might locate a terminal nearby that opened a door to the same area or different goodies.

Now, when we get to an area without the proper skills, we automatically look for the Persuasion approach nearby, the terminal to hack, the stealth route to follow, or the rocket launcher to go postal with Either that, or we return later when we have the right perk or leveled up the right skill. After all, we likely know where all the Bobbleheads are, and the skillbooks, right? It’s still incredible to admire the range of approaches that can be taken at so many points in the game. Still, I found the familiarity of some areas so clear in my mind that I couldn’t help optimize the fun out of them, and this made me realize that, like anything new, it’s only new once.

But it’s the journey and the new vistas that keep us interested. As we leave behind the initial haven of Megaton, and venture further into the Wasteland, the landscapes become more ambitious. The ruins of Washington appear, feeling oppressive and speaking of faded glory, before the path through them is capped by the wonder of Rivet City. Broken buildings and piles of rubble remind us that, graphically, the genre has moved on massively. Texture and lighting effects are quite basic, and the color palette is mercilessly drab. It’s the little things I noticed most too—look around any Fallout 3 interior all these years later, and you’ll quickly realise how little detail there was inside, bar a few tables, scattered stimpacks, busted coffee machines, or perhaps the ubiquitous ‘earnings clipboard.’

Having said all that, this is an area where the game’s modding scene continues to impress and deliver. Texture packages offer a large range of enhanced detail for modern PCs and make a lot of difference in the areas of the game that spring up a lot. Therefore, having sharper details in ruined cities or industrial buildings, and even on individual assets like walkways and office chairs, enriches the experience endlessly. There are even specific mods for increasing the level of immersion to modern levels, like having tents animate as if caught in a breeze or facial sculpture mods that adjust the awkward structures and tones of the vanilla game.

Mind you, the sound design still feels fresh and is filled with excellent environmental effects, as well as that underlying music score. I had forgotten how significant an impact selecting a radio feed makes on the immersion in the world. This design beautifully and awfully captures this sense of isolation when things get quiet far from a settlement. All in all, it still serves as an incredible balance between epic roleplay scores and a wistful longing for a long-disappeared Americana. Voice-over acting is similarly well balanced, with just the right number of grizzled, cynical performances offset by the truly zany, batshit characters. Although well acted, I still feel Fallout and Fallout 2 still have the edge in characterisation and theme—Fallout 3’s voices are just a little too similar in tone, and the writing just a little too straight.

There’s still jank in the quiet moments, too, despite countless patches and mods that address most of the issues. Clipping and level geometry still offer some hilarious moments, as well as some annoying ones. Missions occasionally don’t trigger or end. It’s still stable, though, and most things work how they’re supposed to unless you’re trying to push the game world and systems to their limits. And let’s be fair, a lot of us are doing that.

In addition to the texture packs mentioned above, I settled on the unofficial patch for the game, as well as firearms and Hardcore mods. There are dozens more options, as long as you’re willing to tolerate finding the correct version and comfortable editing and adjusting game folders. Playing the game with the Hardcore mod presented it in a different light and made the choices and some of the meta-gaming mentioned above totally fresh. What do you mean I can’t carry dozens of rounds of ammunition around the Wasteland because it now has a weight value? Suddenly, choosing what firearm to keep and where to store the rest became critical. And as for sleep not healing my broken limbs, well, doctors are not common in the Capital, so I quickly became a character that shambled around at times on one leg and with one arm, praying that the raiders in the distance wouldn’t see me. It’s not for everyone, and the pace of the game slows down immensely when every encounter needs to be calculated carefully as to whether you’ll even survive or what resources you’ll use up to do so. Still, I’d recommend that those who have yet to sample such survival aspects have a go.

Bethesda produced a range of DLC packs supporting Fallout 3, most of which are worth adding for what they offer, especially as the whole bundle is often on sale for a few bucks. Broken Steel is a favourite, offering an increased level cap and a 10-hour narrative exploring the Enclave and the fight against them. It really helps to flesh out the world’s lore whilst adding some additional item goodies in the process. Point Lookout offers a similar level of extra narrative but focuses on the swampy mysteries of Maryland with a more ghoulish bent. It’s worth pointing out that many mods require the DLC (all or part) to work.

Overall, Fallout 3 still stands up all these years later as an engaging open-world RPG. It nails its sense of place and time, and even if its graphical limitations are more noticeable now, the excellent sound design still shines bright. Better still, the open narrative and plentiful places and people to discover still offer emergent storytelling that is at least on par with the best examples today. The systems for interacting with this narrative are still functional, too. However, this is where the aging combat systems and familiar quest design become most apparent and where I found myself battling most against the game. But with the right patches, mods, and a willingness to not fall into familiar choices, I recommend Fallout 3 to those of us who have already completed multiple playthroughs and those who have yet to even set foot in the Wasteland.