Final Fantasy XVI is just around the corner, and it’s the first mainline Final Fantasy release in almost seven(!) years. That’s the longest wait between mainline entries in the series yet. Like many of us, I’ve been inclined to reflect on the legacy of these games, and the little ranking demon in my brain has made me consider how I’d evaluate them against each other.

First things first: This is my personal ranking and does not reflect the opinions of RPGFan at large.

Second, the criteria: For what is a ranked list without clearly defined criteria? With this list, I want to explore what makes the Final Fantasy series special in terms of narrative design innovations. For me, that comes down to the games’ tendency to experiment with the storytelling structure and how it ties its gameplay systems and segments to those stories to create investment in the world. If this list had a thematic sub-title, it would be “A Retrospective on the Series’ Narrative Design Innovations.” At the same time, it doesn’t make too much sense to consider narrative design as something separate from the core game experience, so the games’ overall gameplay factors in here too. Please keep this all in mind when considering the ranking itself.

Before beginning the list proper, I feel I should summarize my connection to the series. Final Fantasy kickstarted my love of videogames. In a way, it was even my entry point to fiction and fantasy in general. Before I could even properly play a videogame, I remember watching my older brothers playing the Final Fantasy games of the SNES and PSX era and becoming enthralled by the worlds they depict and the fact that you, the player, got to be the little sprite or polygon-based protagonists that these weird and fascinating stories revolved around. It wouldn’t even be an exaggeration to say that my initial interest in this series is partly responsible for me now being in a Ph.D. program researching different aspects of narrative design.

But that’s enough prelude. Let’s talk Final Fantasy.

Unranked. Final Fantasy XI + Final Fantasy XIV

I know the Final Fantasy MMOs are as beloved as any game in the series (and more) by some, but I’m going to leave them unranked for a few reasons. Short answer: I haven’t finished either of them. I was too young when Final Fantasy XI came out to be able to convince my parents that they should let me play videogames online, and so my chances of experiencing the game properly have long sailed off. As for Final Fantasy XIV, I haven’t yet had the 500+ hours needed to catch up with all the expansion content. I’m about to begin Shadowbringers and can’t wait to experience what’s ahead (but have to, unfortunately). I’ve already seen enough of FFXIV to get why fans consider it among the best games of the series (or one of the best games of all time, for that matter).

But aside from my inexperience with these titles, and despite Square Enix deciding to name these as mainline entries in the series, they feel apart from the other mainline games. I still feel like the name Final Fantasy Online I + II would have been a more honest naming convention. This doesn’t mean they aren’t of the same quality, but more that they’d need to be judged by a distinct set of criteria. It’s difficult to directly evaluate videogames with a live-service multiplayer component against self-contained single-player experiences that involve one player engaging with a relatively fixed product. Single-player RPGs come with their own set of design approaches and player expectations, and likewise for MMOs. If this decision greatly disturbs you, allow me to introduce a fun, game-like interactive element to the list: pick a spot where you’d like these games to go and put them there! I promise I won’t be upset.

13-11. Final Fantasy I-III

So why did I clump these games into one entry? Well, for one, it would leave me more room to talk about the other (*cough* more interesting) games. But it also felt appropriate to have them stand together to signify the series’ formative years as unremarkable but necessary steps toward greater things.

While the first three Final Fantasy games aren’t bad, it’s difficult to argue that they’re good by modern standards. Whatever the soul of FF might be, and I’ll try to get to that as we go along, the main point I want to make here is that although these first three games all bear the Final Fantasy moniker, the series had yet to find itself. Especially playing these games now, they each feel like dry runs for a series waiting to execute on ideas too big for the budding videogame landscape of the 1980s. Final Fantasy lays a solid foundation for the series with its experimental class system and more esoteric plot points. Final Fantasy II‘s gameplay systems are a mess, but its more character- and emotion-driven story is an early sign of the series’ narrative ambitions. And Final Fantasy III is effectively a prototype for the far superior Final Fantasy V. The bottom line is that I wouldn’t recommend these games to anyone besides those interested in tracing the history of the series.

10. Final Fantasy XIII

Final Fantasy XIII is actually a solid game, but it has some glaring issues. First, there’s the awkward structure. The first part of the game, which might qualify as the longest tutorial section in RPG history, is an extensive stroll through linear levels interspersed with strategically satisfying and consistently engaging battles. The battle system is so nuanced that the designers spend around 50 hours in these level funnels slowly acquainting the player with its potential. The environments are lushly realized in the series’ first jab at HD graphics, making it even more disappointing they are inaccessible beyond their rigid boundaries. Not to mention how disconnected each zone feels from one another spatially. After spending tens of hours in Cocoon’s varied locations, it felt like a journey through disparate art assets rather than a coherent and living world. This translates to its cast as well, featuring characters who constantly clash and are working together only due to survival necessity. If FFXIII as a whole had a theme, it would be disconnection.

Then the game opens up as the party ends up on a new and much more open world, Pulse. Here, the training wheels fly off Final Fantasy XIII’s metaphorical bicycle. The Pulse section finally sets the player free to explore and take on a variety of optional quests with wild variations in difficulty—catering to players who just want to grind enough to finish the game as well as those who want to dedicate themselves to mastering the strongest abilities and the intricacies of the battle system. It’s a shame these quests lack much personality, given by floating rocks (sorry, “Cie’th Stones”) and offering very little narrative intrigue or character development. FFXIII doesn’t always seem to know what it wants to be, but at least not all its swings are misses.

Finally, shout out to the soundtrack for getting the most plays of any during my FFXV road trip.

9. Final Fantasy IX

Just about every one of these Final Fantasy games (especially starting now) is a valid candidate for being someone’s favorite—and Final Fantasy IX is the favorite of many, including series creator Hironobu Sakaguchi himself. It’s a loving amalgamation of everything the series has tried to be up to this point. Whimsical fantasy; affecting melodrama; character class systems; convoluted theological/philosophical themes: it’s all here and it all works well together. But in synthesizing the many aesthetics of the series up to this point, FFIX doesn’t offer much new. It would rather appease series fans than challenge them with fresh ideas. There’s a great comfort to be found in this game, but it doesn’t push many boundaries. And I’d argue that the Final Fantasy series pre- and post-FFIX has been all about pushing boundaries.

There are many narrative set pieces here that are a joy to experience. Even in the opening hours, we get to explore the crowded streets of Alexandria from Vivi’s alienated perspective, put on a stage play performance as the charismatic Zidane, and act like a narc in Alexandria’s castle as the royal bodyguard Steiner. These three characters, along with Princess Garnet/Dagger, are the core of this game both narratively and mechanically. They’re so essential it kind of leaves the other party members behind to eat their dirt. And while the classic squad of Thief/White Mage/Black Mage/Fighter that this party composition offers is satisfying in its own right, the game’s battles and customization options can often feel slow and unremarkable. I love this game for its heart (and soundtrack!), but after playing it through to completion once, it’s never called back to me. I had an undeniably good time, but I felt like I already saw all there was to see.

8. Final Fantasy V

Final Fantasy V is the hardcore player’s Final Fantasy. Its interchangeable job system is a playground for experimental character building. Its difficulty feels remarkably well-balanced for a series that often feels mechanically busted. It’s just a very good game. That’s both the highest compliment and most significant criticism I can give it. The series has become synonymous with a biting-off-more-than-it-can-chew narrative ambition that is prominently missing in FFV’s confidently simple and good-natured premise. This isn’t even to say that the game doesn’t pull off a few interesting tricks during its runtime. There’s aliens, disguised identities, an alternate world, a memorable dungeon that runs on a countdown timer, and a major character death. It’s all engaging stuff! I even like how the relative lack of characterization for the main party allows players to develop them in their headcanon through the jobs they assign to them. If FFIV is what FFII should’ve been, then FFV is what FFIII should’ve been.

If it sounds like I’m uninterested in criticizing this game, it’s because I am. But that only goes to show that what the ‘best’ Final Fantasy games (in this guy’s humble opinion, anyways) have to offer is more than just a good game. Final Fantasy V’s immediate predecessor and successor showed that videogames could offer more than a fun time. They could be structurally interesting, emotionally charged, and offer meaningfully embodied character development. If what matters most to you in a classic JRPG is satisfying and rewarding turn-based gameplay, this might be the Final Fantasy for you. But if you’re looking for something more intangible from your RPGs, well, keep reading.

7. Final Fantasy XII

Like FFV, Final Fantasy XII shows great confidence in the elegance of its gameplay. It’s built as a sort of single-player MMO experience with the impressively deep and original gambit system that effectively allows players to program their party’s behaviors so that battles play themselves out according to equipped AI commands. It remains a novel RPG battle system, and the gameplay (I hear) is even better in the Zodiac Age version (which I haven’t played, for the record). Like an MMO, most of FFXII’s gameplay revolves around exploring massive areas, picking and choosing combat encounters, and drinking in the lovingly designed world. There’s lots of stuff to do for whoever likes having lots of stuff to do, and in a way, this feels like the most complete and coherent world depicted in a Final Fantasy game. For players looking for a more curated narrative experience, however, FFXII’s MMO aspects can feel progressively more like grinding for grinding’s sake. It’s interesting looking back on FFXII after playing Final Fantasy XIV, as the latter—despite being an actual MMO—puts so much more character and worldbuilding flavor in its massive explorable environments (particularly in the expansions).

I love the vibe of Ivalice, and I admire what this game ended up being, but I can’t help but wonder what it would’ve been had Yasumi Matsuno remained at the helm throughout development. Maybe it would have experimented more with its narrative design, or maybe we wouldn’t have had to deal with Vaan and Penelo… Sorry, I should stop nitpicking this game and say something positive. Clearly, I still really like it to put it above FFV and FFIX. I love the way it looks and sounds! I love how huge and alive the cities feel! I love the Shakespearean writing and the maturity of political detail expressed in the cutscenes and NPC dialogue! And Darth Vader Gabranth is so cool!

6. Final Fantasy XV

This is probably my most biased placement. Final Fantasy XV, like FFXIII, is a bit of a mess—but it’s a fascinating mess with personality bursting out of the cracks in its design. Instead of investing in a competent battle system or making the story feel structurally complete, we got a friendship simulator with comforting campfires, a sweet ride for blasting Final Fantasy tunes while riding shotgun, and an excellent fishing minigame. Instead of a programmable AI battle system, we got hangout-able AI boys. If FFXII is an exercise in clean execution that sometimes lacks flavour, FFXV is a mouthful of peanut butter and jam. The battle system is wonky, but it tries to integrate character interactions in a smooth and involving way. And while most of the side quests are remarkably uninteresting, they importantly pad out the hang out time and contribute a lot to the game’s endearing road trip vibe.

The developers tried to tell Final Fantasy XV’s story as a transmedia epic. Just playing the videogame won’t get you the full picture; you have to watch the CGI feature film, Kingsglaive, the episodic anime flashbacks (Brotherhood) on YouTube, and play the supporting character-focused DLC chapters. Oh, and the novel is also there. While the quality of this content varies, it’s a fascinating idea that only a videogame megacorp like Square Enix could attempt at that scale. Then there’s the story contained in the game itself, fractured between plot-heavy linear chapters and player-driven exploratory chapters. It’s an odd and uneven structure, but it naturally adjusts to the ebbs and flows of the characters’ lives and the surprises of the plot in a way that most AAA videogames are too risk-averse to attempt. Its cohesion as a game suffered to accommodate the ambition of the story as a videogame. Instead of simply iterating on what we understand a videogame to be, it wants to show us a clearer peak at what they could be. The result is a flawed yet singular product that I will go to bat for every time someone throws some cheap shots its way. We need to encourage this game’s experimentation with the RPG genre—not chastise it.

5. Final Fantasy VIII

Speaking of black sheep, Final Fantasy VIII was the leading candidate for that series title until FFXV rolled out in its souped-up Regalia. Here’s another game whose ideas were perhaps too big to cohesively execute. In a way, FFVIII felt like a natural continuation of FFVII’s angst-driven maturity, except you made money through your student salary, got new equipment by combining specific enemy loot drops, and leveled through equipping junctioning the magic you ‘Draw’ from enemies and some swirly energy things in the environment. Regardless of how you might feel about these changes, they manage to feel fresh to this day and point toward the subversion of taken-for-granted RPG conventions that today’s indie scene relishes in. Not to mention that creatively discovering ways to exploit and break these systems becomes its own enjoyable metagame on top of the experimental foundation.

Then there’s the fever dream of a story. It begins as an anime-like plot about youth studying and fighting together in a military academy but later becomes more defined by its interestingly bizarre narrative set pieces. The disorienting Laguna sequences. The horror-romance space station stuff. The stupid(ly awesome) orphanage plot twist. These moments have all burned themselves into my brain as proof that videogame storytelling can be borderline incoherent in a way that feels naturally compelling for the medium (setting the stage for Kingdom Hearts). It’s certainly not the best main cast the series has seen, but with Squall and Rinoa’s awkward yet genuine teenage romance at its heart, it manages to end off as a poignant reflection on love and maturity.

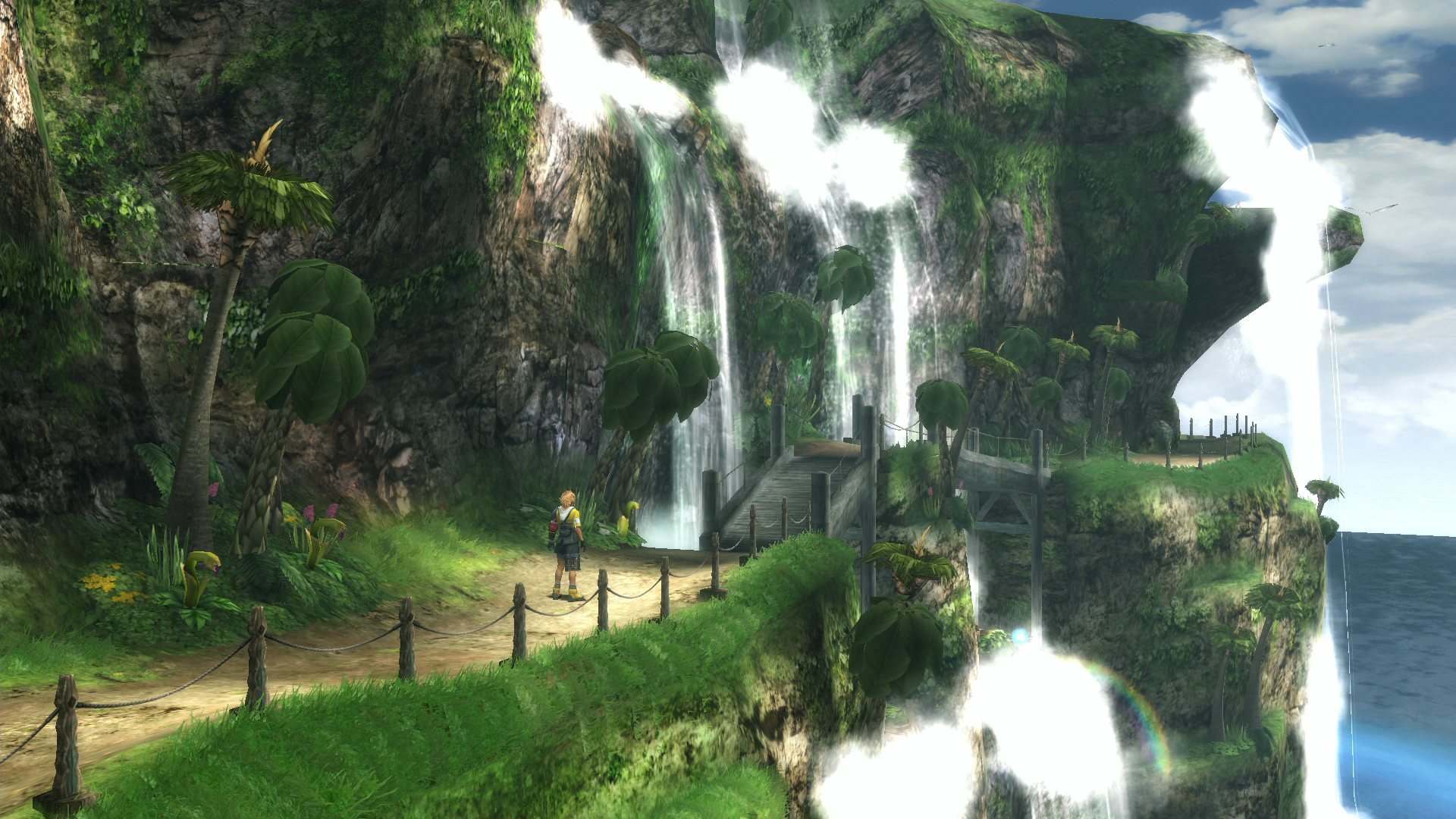

4. Final Fantasy X

I already criticized FFXIII for the linear designs of its Cocoon levels, so how to justify Final Fantasy X‘s many similarly narrow walkable paths? Easy: it’s the world. Traveling through Spira’s regions feels like a coherent journey through distinct parts of a land brimming with life and culture. The visually and musically defined aesthetic of each region manages to make them feel both unique and connected. To add to this impressive cohesion, the pilgrimage plot works so well for making the party feel like a unit of individuals that belong together and play off each other rather than the assorted collection of whoevers that some FF parties can begin to feel like by the end game. The linear levels and the dynamic camera that weaves through them also contribute to a steadily contemplative, almost epic poem-like pacing that provides a welcome alternative to the samey structure of most PSX RPGs.

The battle system has also aged quite nicely. Sure, it was sad to see the series’ long-standing ATB go, but FFX’s turn order display, paired with its interchangeable party members, made for strategic yet snappy combat. The sphere grid is… okay. And the temples’ sphere puzzles are… not bad! But what really makes Final Fantasy X stand out is how the game’s structure builds around its narrative design—and how naturally this translates to the game’s sense of worldbuilding and character development.

Oh, and Squeenix, if you’re reading: please consider partnering with the NBA 2K devs for a full-fledged Blitzball RPG/sports game.

3. Final Fantasy VII

Well, we’re down to the big three. What’s interesting about each of these next three Final Fantasy games is that none of them do anything particularly ground-breaking in terms of their RPG systems. What truly made these legendary videogames is that they showed the player the medium’s potential for character-driven storytelling. They proved that the player’s avatar did not have to be a silent blank slate for the player’s self-projection, but that having the player project themselves into an established character with their own motivations made for an interesting tension between identification and spectatorship. We may not identify with or even like Cloud’s cool-headed ambivalence when we first get to know him in Final Fantasy VII, but through embodying him on his (frankly ludicrous) journey of self-discovery, we may begin to understand him as a literal extension of ourselves.

FFVII’s opening Midgar section is still one of the greatest segments in videogame history. It has a cinematic pacing that feels miraculous for a turn-based RPG yet still gives the player some exploratory breathing room in areas like the Sector 7 Slums and Wall Market. It throws the player into multiple structurally unique narrative set-pieces like the bombing mission and the Don Corneo questline. And it ends off with a weirdly awesome motorcycle escape minigame. Speaking of which, FFVII easily has the best minigames in the series in the form of optional diversions (via the to-this-day spectacular Golden Saucer) and as a way of framing specific moments in the story that introduce some gameplay variety. The rest of the game after Midgar is pretty darn good too! It manages to stretch that masterful design of the opening hours into a more conventional pace and structure.

Final Fantasy games before FFVII already had a cinematic sensibility to them, but the PSX’s hardware truly allowed that to develop into a singular RPG experience no other developer could offer. When it released, Final Fantasy VII was, perhaps above all, a technical marvel that combined 3D models, pre-rendered backgrounds, fixed and dynamic camera work, and CGI cutscenes into a fluid aesthetic that’s still impressive to look at (barring those cube hands).

2. Final Fantasy IV

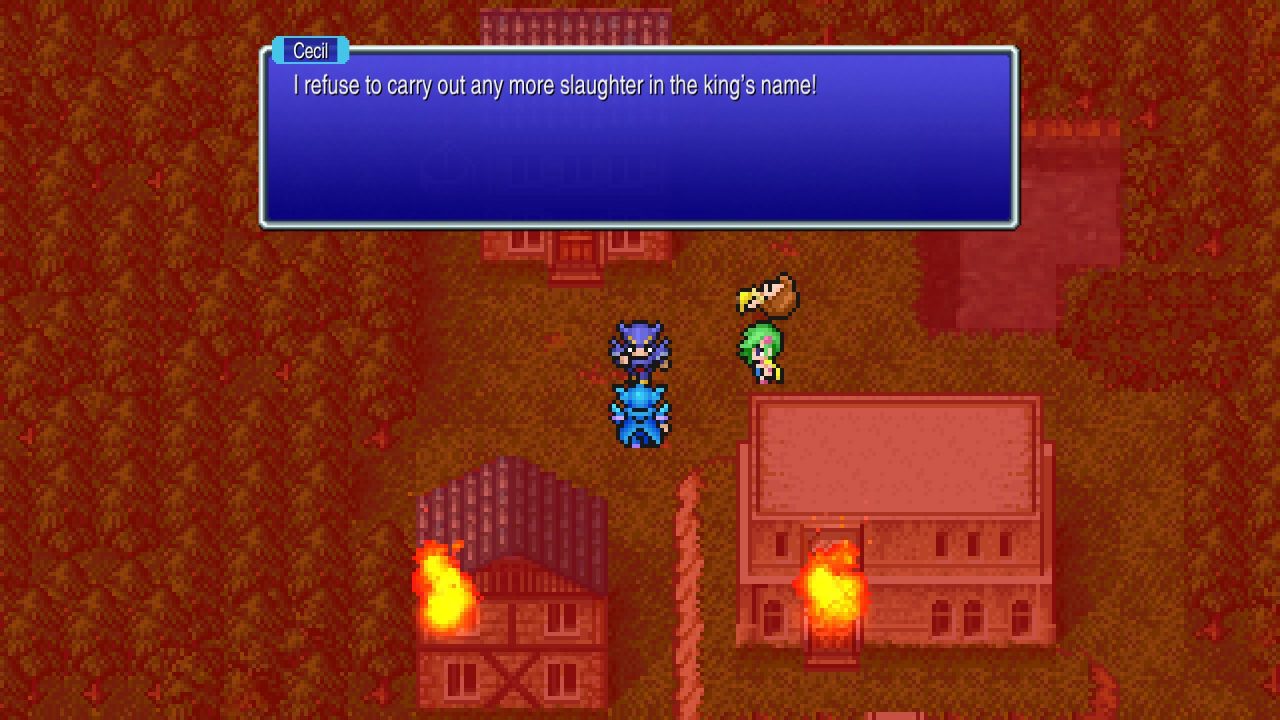

Final Fantasy IV begins with watching the protagonist, Cecil, commit war crimes for the Kingdom of Baron. This event—paired with Cecil’s “Dark Knight” job class and the menacing, faceless helmet that takes up his character portrait in the menu—establishes that he is not a hero. It’s notable that this first scene has the player watch rather than act. By the time the player controls Cecil, he has begun a path to redemption that is the driving force of the plot. Then, at a climactic moment of the game atop Mount Ordeals, Cecil completes a change of heart that becomes reflected by a shift in his character class (into a Paladin capable of defending others and healing). He receives a new sprite and face-revealing character portrait and also reverts to Level 1. Then, to top it all off, we must fight one-on-one against Cecil’s Dark Knight self by defending against his relentless attacks until he vanishes. It’s a poetic way of representing a character’s rebirth that plays with genre conventions such as class, leveling, and battle systems. I think it’s also one of the most significant narrative design moments in videogame history.

Final Fantasy IV’s portrayal of an anti-hero protagonist paved the way for the many modern videogames interested in embodying players in increasingly nuanced character portrayals. And it did this in 1991 with a turn-based battle system. It’s a testament to Square’s creativity at the time that they portrayed so many distinct moments with the standard JRPG format. The way characters come and go from the party works narratively by allowing most of the cast to express their own agency in the world and mechanically by being able to build gameplay segments and combat encounters around a particular party composition. This frequent switching allows the plot to move briskly and for the gameplay to remain consistently engaging, resulting in a game that continues to age gracefully.

It’s also worth mentioning that this was the first Final Fantasy game where Nobuo Uematsu composed individual character themes, which would become a staple for the series’ ability to weave emotive musical motifs into its storytelling.

1. Final Fantasy VI

Full disclosure: Final Fantasy VI is my favorite videogame of all time. It retains the title pretty much by default, as it was the first to truly open my eyes to the medium’s potential for narrative expression. FFVI still feels more mature than many of today’s hyper-realistic M-rated games—despite also leaving room for silliness, such as suplexing a train or battling a conceited, belligerent octopus. On first impression, the story is an exciting Star Wars-like tale about rebellion against an evil empire. But, more importantly, it’s also a game about adults with adult problems.

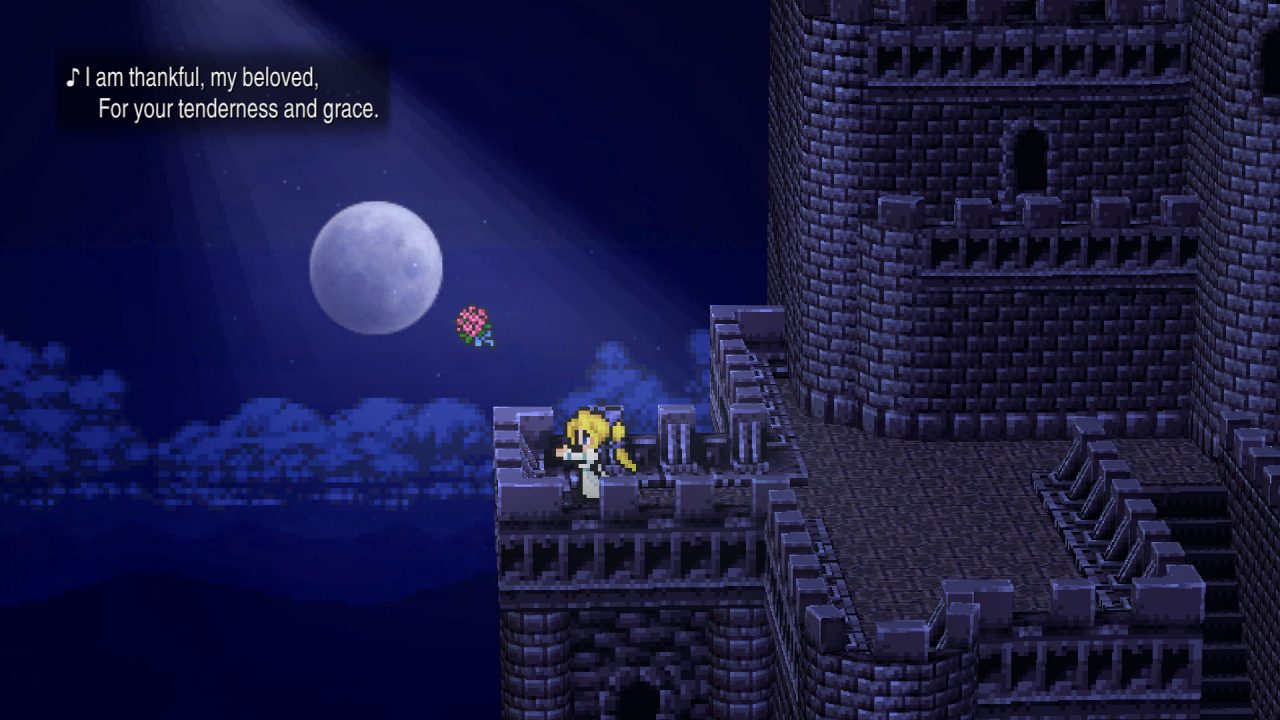

The game’s unforgettable structure bolsters this impressive character development. The World of Balance half moves like a conventional yet dramatically engaging RPG introducing the player to a great cast of clearly defined characters. What isn’t conventional is how often the game throws us into a new character’s perspective. The game does this brilliantly during its ambitious narrative set pieces, like the famous Opera scene or the branching story segment that temporarily divides the plot into three strands. This is also the first Final Fantasy game without character classes. Instead, each character has a distinct skill to use in battle that speaks to their individual capabilities and personality. Meanwhile, anyone can learn magic by equipping them with magicite, showing how the realm’s Espers are being harvested to advance human power.

Then there’s the World of Ruin, which might still be the best representation of an apocalypse in any videogame. Not only does the world become an uncanny distortion of its former self, but our massive cast of characters is dispersed until we eventually find them coping with their personal trauma. From Terra’s search for non-violent meaning by helping orphans; to Cyan’s lonely pen palling; or Locke’s desperate attempt to bring back his coma-ridden lover—each of these recruitment quests breathes a nuanced humanity into characters we thought we already knew. Between these two halves, FFVI is Mass Effect and Mass Effect 2 rolled into the same game over ten years before Mass Effect was a thing.

Final Fantasy VI is at the top of this list because it’s still a golden standard for RPG narrative design.

Editor’s Addendum: If you want even more big picture Final Fantasy features, we recommend you also take a look at the following!