We make the most of the one life we have by layering it with diverse experiences and developing meaningful connections with others. Fantasy Life i: The Girl Who Steals Time seeks to replicate this intricate tapestry by weaving together a variety of gameplay styles and risks becoming a “Jack of all trades, master of none” in the process. While Fantasy Life i‘s many facets each have their own strengths and imperfections, the game is still a cohesive experience that manages to capture some of the best elements of its many influences.

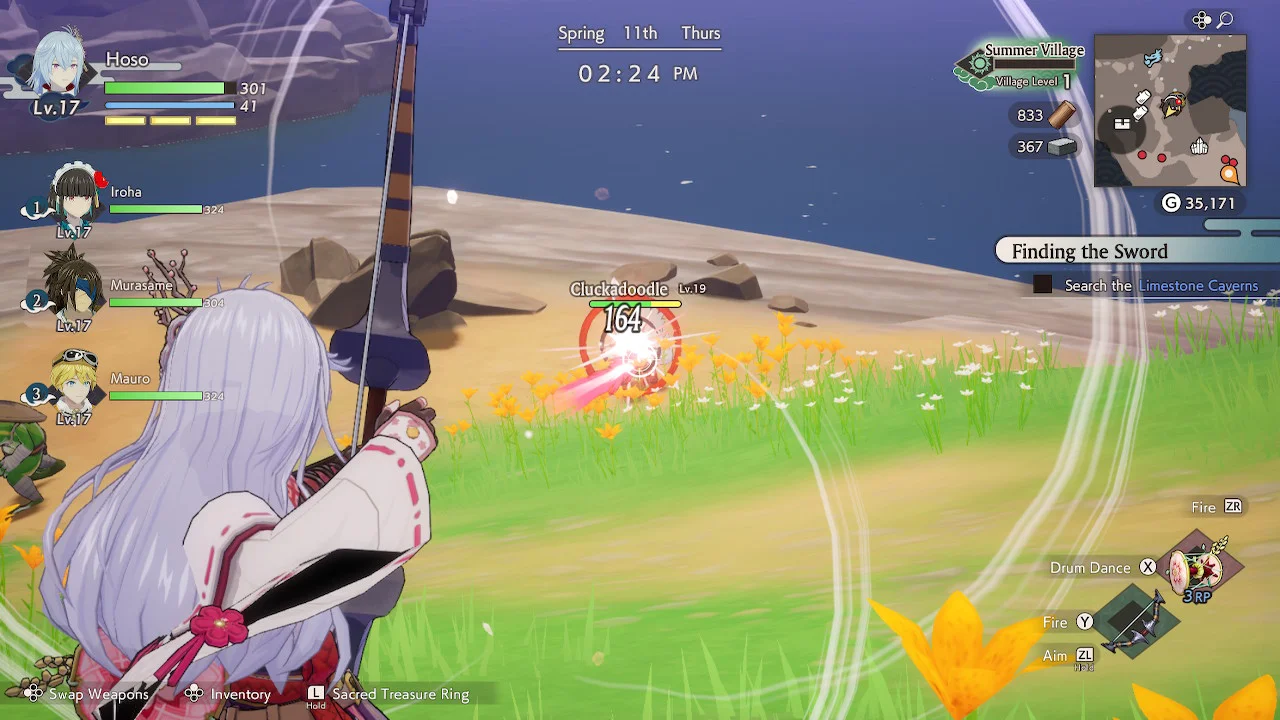

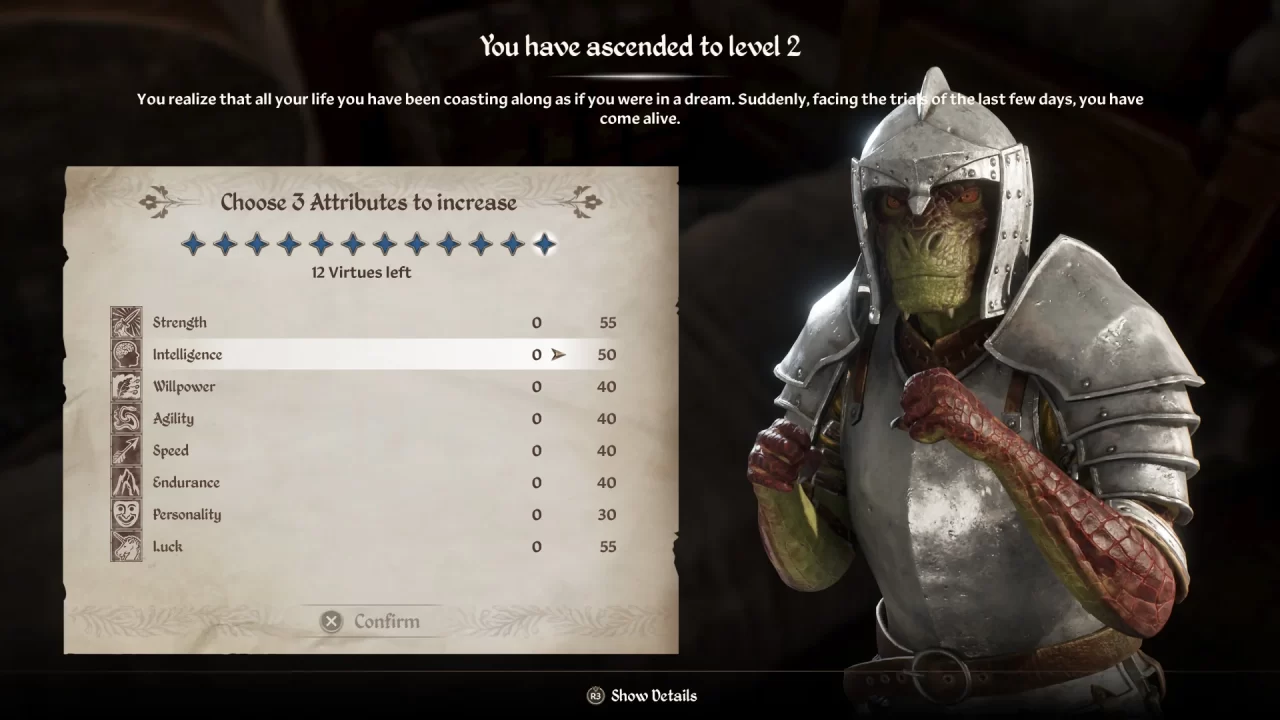

Fourteen classes, which the game calls “Lives,” are at the heart of Fantasy Life i. Once you unlock a Life, you can seamlessly swap between them as you go about your adventure. The Lives also support each other, allowing you to be entirely self-sufficient. When you see a fish’s shadow in the water, you can brandish your fishing rod with the press of the A button and reel in the day’s catch. You can then make your way to a crafting table and cook that fish into a meal that temporarily improves your gathering ability. To make the most of that buff, you can mine ore from the nearby deposits and forge it into a weapon to improve your Combat Life’s stats. This can help you take down a tough monster, which an NPC requested you defeat. You can then use the money reward from the request to purchase new crafting recipes from the game’s many vendors, starting the cycle anew.

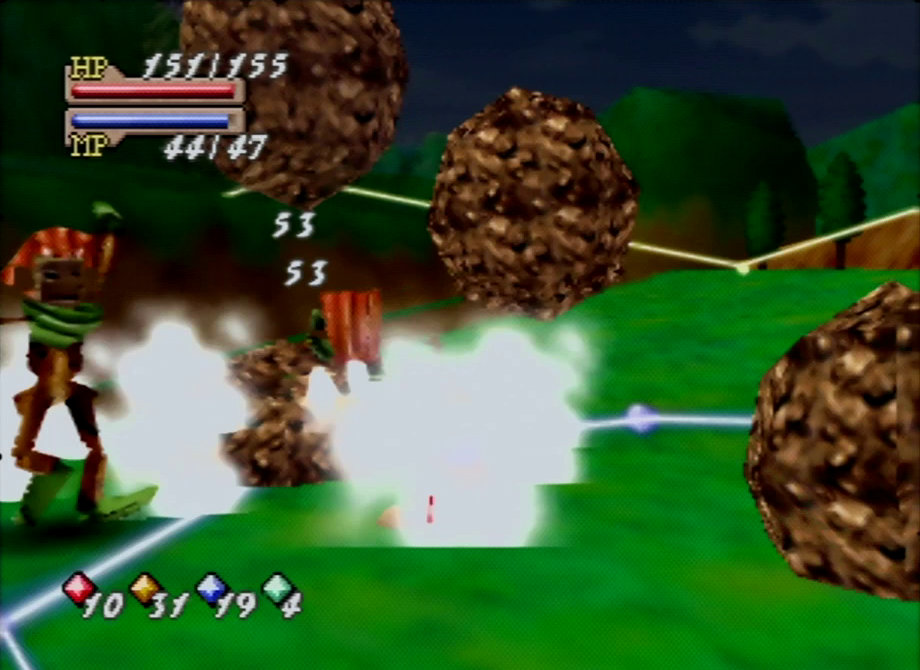

You repeat this cycle across the numerous worlds of Fantasy Life i, some of which will be familiar to fans of the Nintendo Switch’s impressive game lineup. Fantasy Life i’s world is split into three groups: the present, the past, and Ginormosia. Just like how each Life supports the rest, exploring one world enriches your experience in the others. There are four islands in the past, each with materials to gather, dungeons to explore, monsters to battle, and NPCs to assist. In Ginormosia, you begin to experience déjà vu: the large island has 15 sections, each with many hidden discoverables. There are shrines with puzzles to solve, little green plant-like creatures called Leafe to find, and towers that reveal the area’s map details when you activate them with your tablet. Yes, you read that right: one-third of Fantasy Life i is a miniaturized The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild.

While understandably not as extensive as the actual Breath of the Wild, exploring Ginormosia is still an enjoyable activity that easily distracts you from progressing through the game’s main story. Ginormosia’s diverse areas offer plenty of collectible materials to help you with crafting or completing NPC requests. If you’re especially thorough in your exploration, you’ll even find exclusive recipes for legendary weapons and tools. The best things you can find in Ginormosia, however, aren’t really things at all, even if they might look that way: Strangelings.

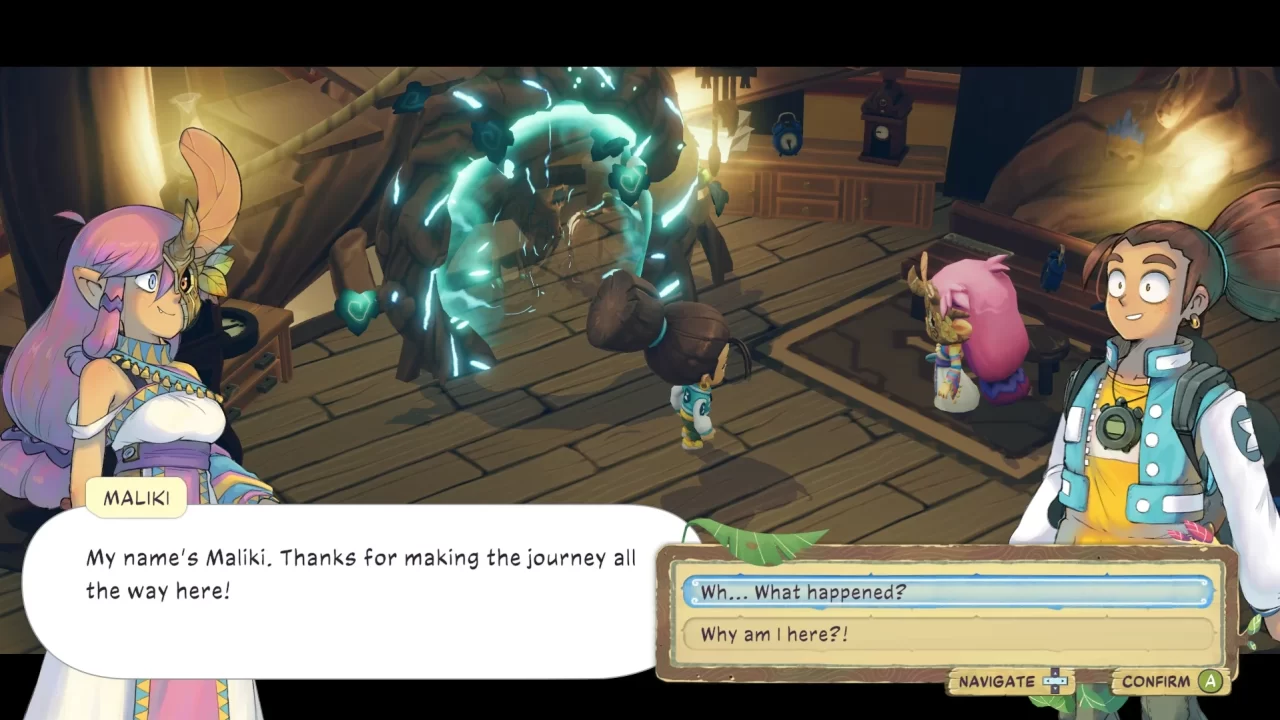

Strangelings are people transformed into inanimate objects. You can randomly obtain Strangelings by defeating certain enemies throughout the game, but you’re guaranteed to rescue one when you solve a Ginormosia shrine puzzle. In your home base in the present, you can restore Strangelings to their human forms using Celestia’s Gifts, which you get by sprucing up the island your base is located on. This contributes to part of Fantasy Life i‘s positive feedback loop, since the Strangelings you restore help you out with your Lives as well as your base. Up to three restored characters can join you on your adventures, and they contribute based on their own Life. Combat-focused characters join you in battle, while Gathering-focused characters join you when you start to mine ore or chop trees. When you’re ready to craft something, you can assign up to two characters with the appropriate Life to help you, boosting your crafting stats and even offering other bonuses as you increase your friendship with them.

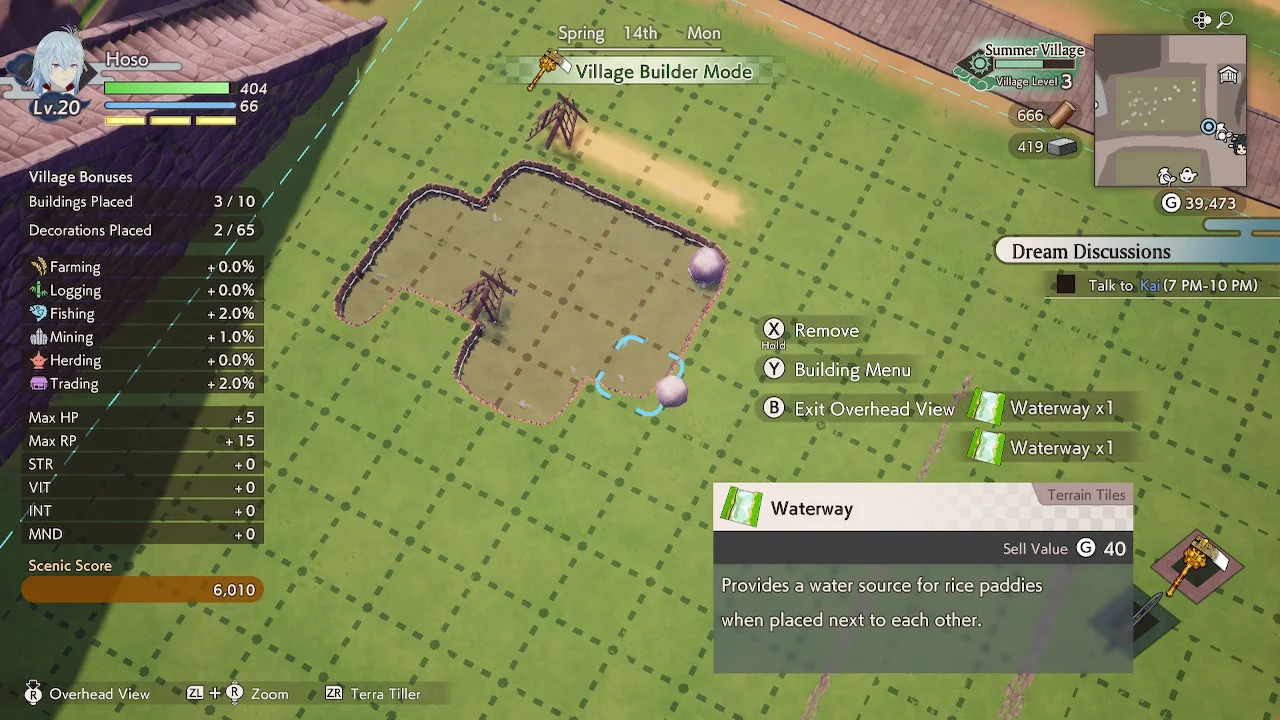

When you’re not actively pursuing your Lives, the characters you’ve rescued can help you clear out rubble in the area around your base, providing more room to build houses or decorate with the furniture you’ve crafted. Developing your base’s island, building houses for your residents, and renovating your own home all contribute to your island’s star rating, and the better your rating, the more Celestia’s Gifts you can obtain each day and the lower the cost of reverting a Strangeling becomes. And as you progress through the game’s story, you also unlock landscaping features including elevation, waterways, and paths. If all of this sounds strangely familiar, that’s because Fantasy Life i‘s present day is a scaled-down replica of Animal Crossing: New Horizons, right down to the daily activities presented as stamp cards that grant you extra Celestia’s Gifts. As distinct as the home base gameplay is compared to the rest of the game, it’s a great place to settle down and make use of the skills you’ve developed and items you’ve crafted in the past and Ginormosia.

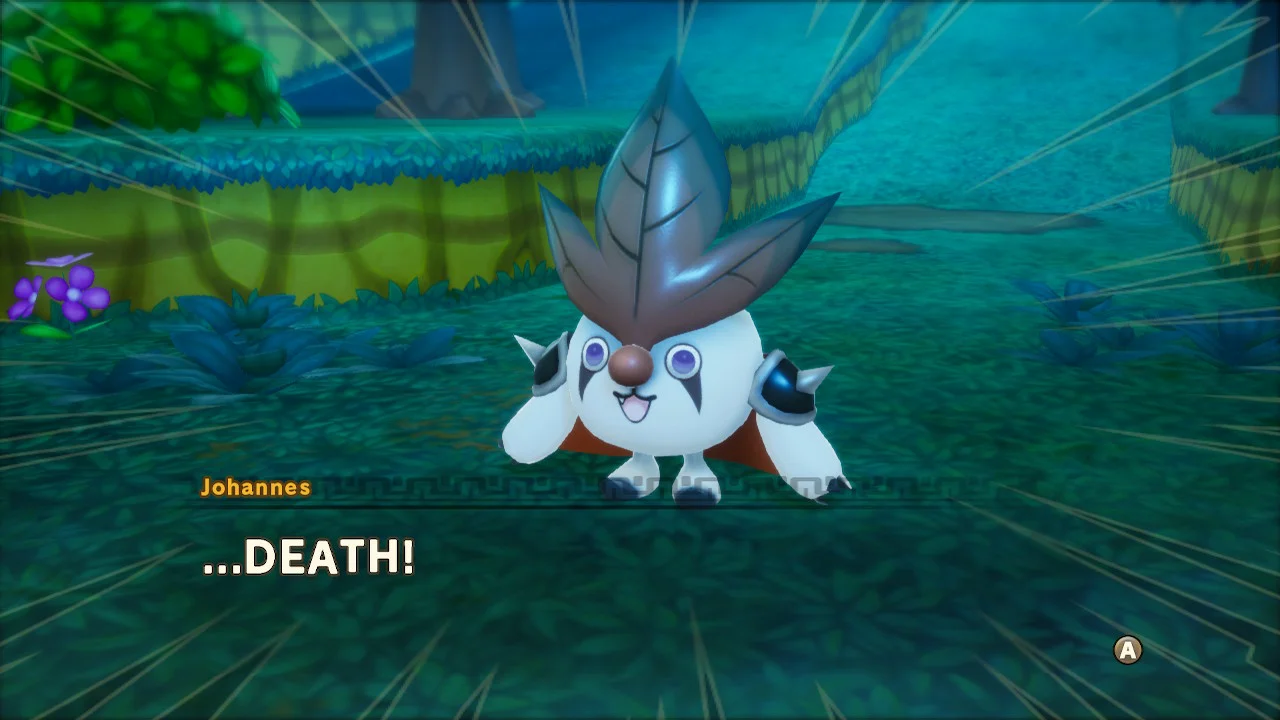

Unfortunately, for all the emphasis it places on togetherness, Fantasy Life i‘s biggest weakness is in its characters and the story surrounding them. While there are some charming cast members, such as a group of usually angelic-singing Leafes starting a death metal band called “Death Ghost,” the characters are almost always uninteresting. Characters in the main story help each other because helping others is the right thing to do. It’s a respectable mindset to abide by, but it stifles the characters by flattening their motivations. Outside of the main story, islanders have generic chats with each other, but nothing that deepens their individual personalities or relationships.

The minimal voice acting also does the cast no favors. You have to endure all-too-repetitive one-liners from your party members during exploration which don’t add any depth to anyone, like the miner Duglas insisting you “Show [him] what you’ve got” every time you start a gathering activity. Story scenes aren’t fully voiced, instead opting for “generic” bite-sized voice clips assigned to each text box. Where this execution fails is how the clips almost never match the severity or context of the assigned dialog. An especially egregious example is a series of scenes with the edgelord character Glenn’s voice always saying flatly, “Heeeey, over heeere” even when you’re already next to him, followed by a dangerous battle that leaves characters seriously hurt. One of the main heroine Rem’s voice lines during this scene includes a demure “Excuse me…” when her written dialog is a panicked, “Outside, quickly!” The stark dissonance between what a character says and what their voice line says further distances your connection to them, and is shocking for a game that otherwise emphasizes cohesion.

The story connecting the game’s distinct facets is also lackluster. There are some endearing story beats, like being led through a Lost Woods-style forest by following Death Ghost’s headbanging beats, and a few heartfelt tropes like flashbacks showing the villain before his fall. But they don’t manage to deepen the overall surface-level narrative. Characters want to go on adventures, and as they do, they get to help each other the same way the different time periods and Lives intertwine—it’s a lovely sentiment, but lacks elevation due to the underwhelming cast. In the grand scheme of the game, it’s easy to overlook Fantasy Life i‘s story as you get caught in the loop of exploring, gathering, crafting, and building your home base. But in order to unlock all the game has to offer, including all the Lives and base camp upgrades, you have to trudge through the main campaign. It’s a minor inconvenience, but a distraction all the same from the game’s best features.

What Fantasy Life i does best is bringing together different game styles and having them work together in such a way that it becomes very easy to get caught in its cycle. Although some minor hiccups are afoot, the game is ultimately greater than the sum of its parts, just like what happens when you bring together all sorts of experiences to contribute to a rich, intricate life tapestry. The implementation of gameplay from some of the Switch’s “greatest hits” also makes Fantasy Life i feel like a spiritual send-off, synthesizing blasts from the system’s past in a way that keeps them fresh for the game’s future. Fantasy Life i: The Girl Who Steals Time is a time-stealer, ensuring its most important features are fun and relevant to the rest of its offerings.