The horror-adventure genre has to be one of the hardest to create within. Unlike horror movies, which can be humongous cash cows thanks to low budgets and cheap thrills, horror-adventure games require a delicate balance between strong game design and immersion. Rely too heavily on gamification, and players get taken out of the experience just to find some hidden goodies. Instead of being terrified of walking down that hallway, players stare at the walls for secrets so that they can unlock all of the game art. That’s antithetical to the whole point of playing a scary game. REANIMAL straddles this line with expertise.

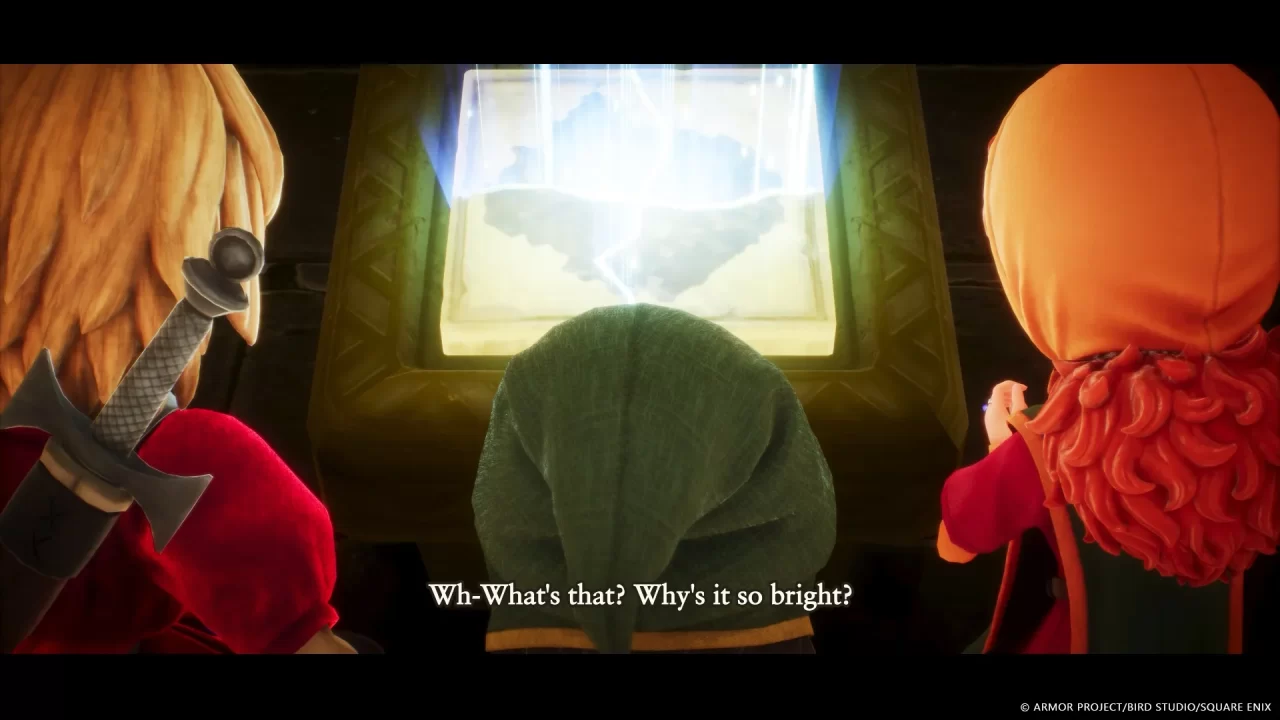

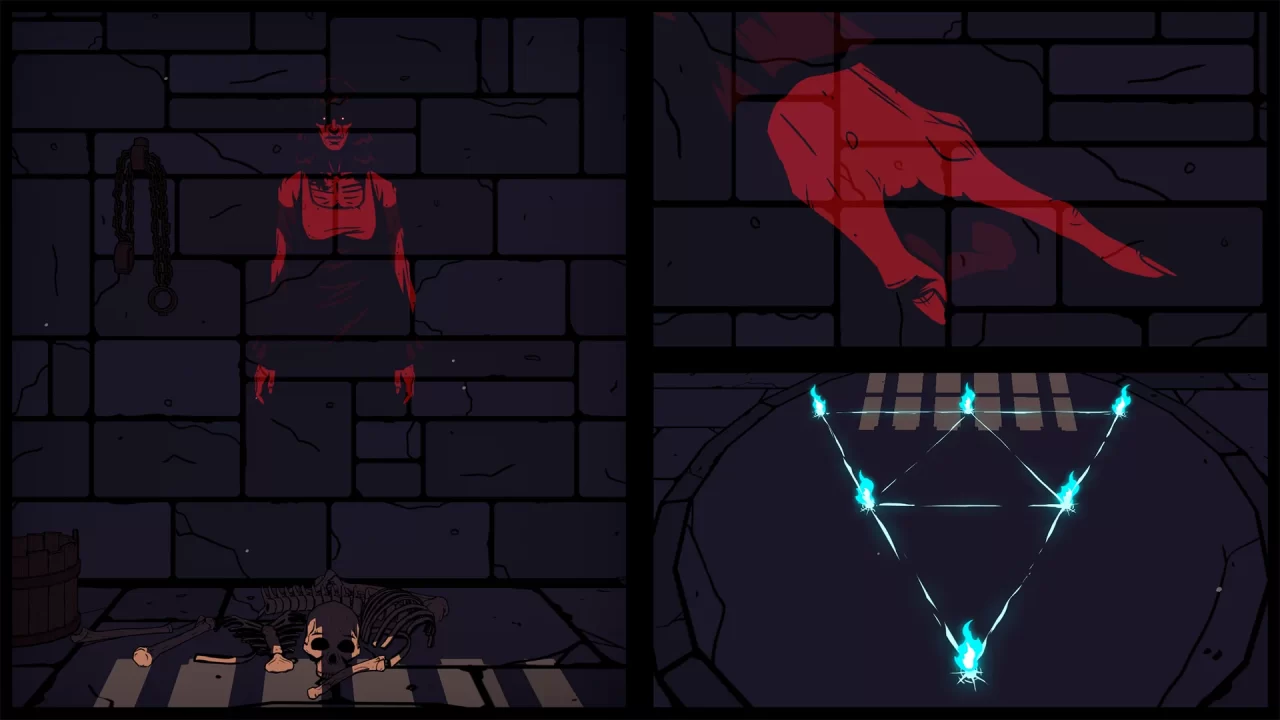

Travel through hell as a boy and a girl in search of lost friends. At least that’s what the press release says. REANIMAL says a lot with few words, though what it’s saying isn’t always clear. Instead of plot-delivery and characterization, we receive haunting, creepy vibes and tension. Being unclear for mystery’s sake isn’t necessarily art or clever storytelling. Thankfully, the incredible production value, combined with this opacity, leads us to believe that metaphors and analogies reign supreme. By the end, I urgently wanted to know what was going on and had a few theories. This is some good ol’ fashioned mind-chew.

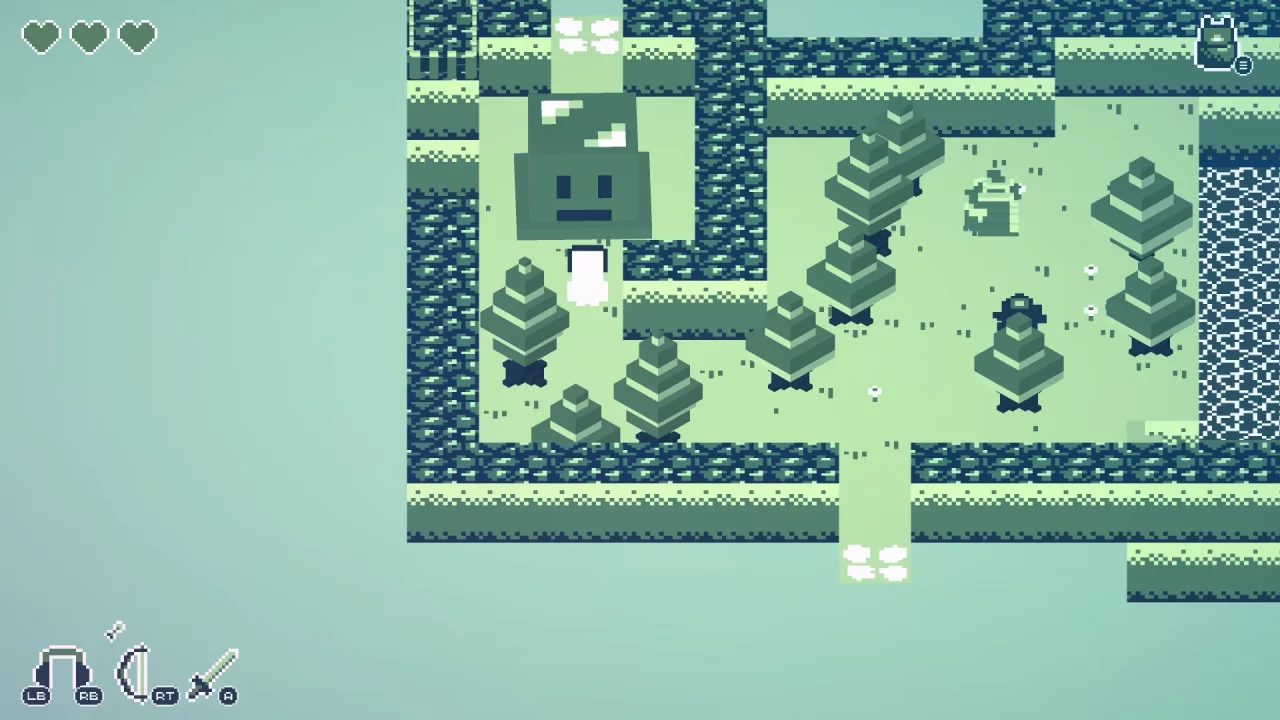

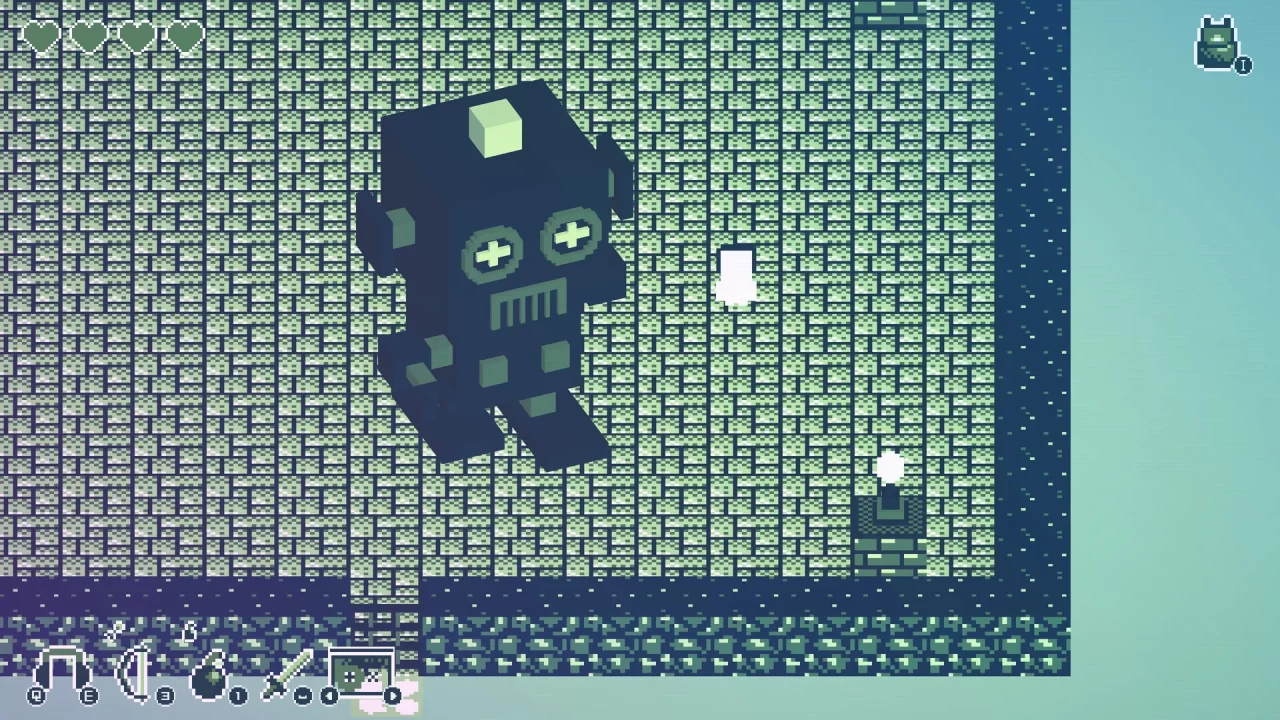

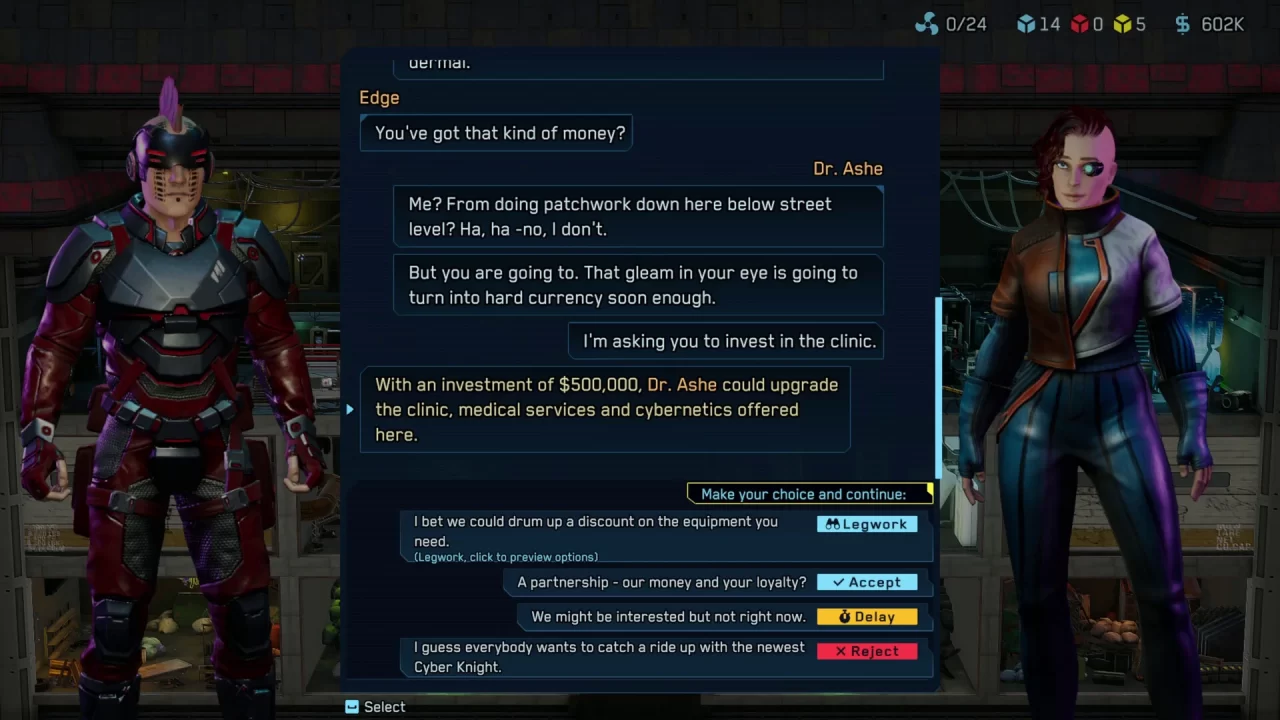

What literally happens on the screen is that a boy and girl venture into an extremely gray, wartorn city in search of friends. In single- or two-player, the boy and girl navigate ruined buildings, eerie forests, and murky waters to find ways past gates, monsters, and an assortment of other obstacles. The words exchanged often relate to a desire to go home and an urgency for the way things were, but nothing is ever expressed concretely. Deranged humans and deformed animals chase the children down hallways, awkwardly arranged communal living spaces, and tunnels. The duo flit about to-and-fro until some unclear goal is achieved by the end of REANIMAL.

While only about four hours at a $40 price point, REANIMAL screams (or bleats) quality. Your physical time with the game may be brief—with promised DLC on the way—but REANIMAL will remain with you for at least a little while post-credits. The clincher with titles like these is that the developers need to give you just enough to want to theorize meaning and revisit the world during idle hours in bed or on the commute. If you’re looking for quantity for your dollar, steer clear, but if you want immersive storytelling that delivers a story like no other game, this may be what you need.

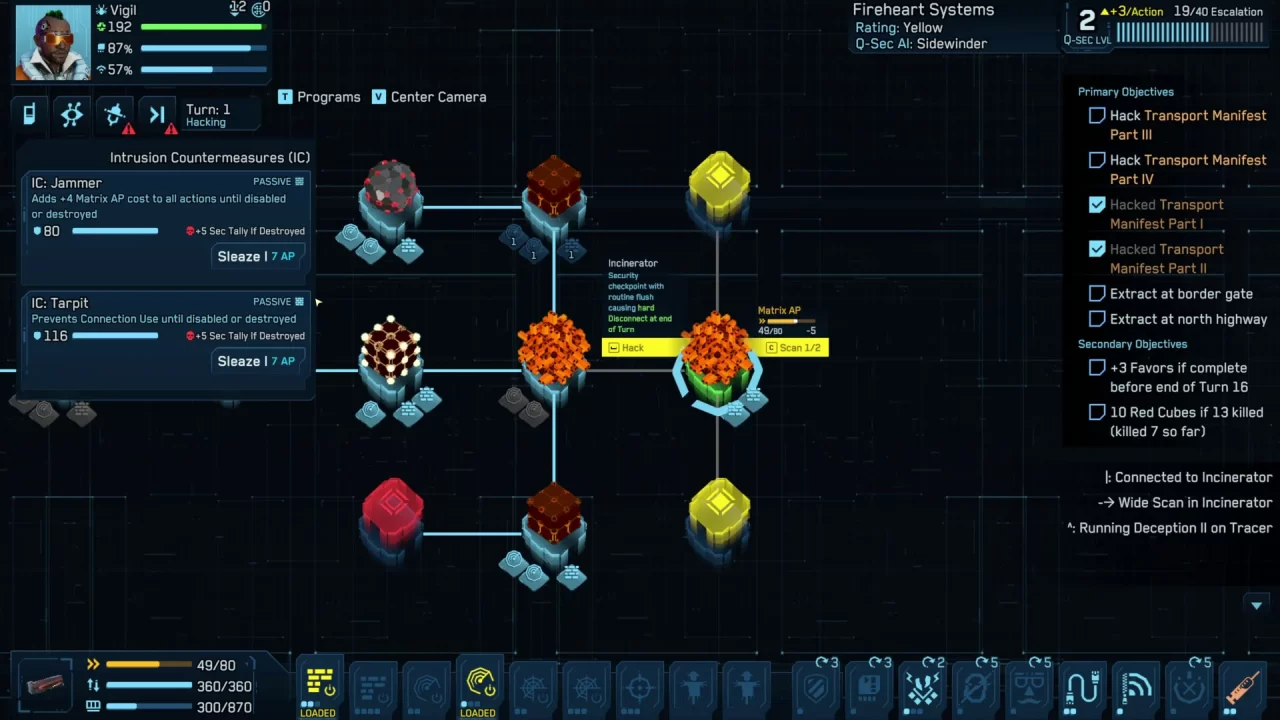

The beautiful quality of storytelling in video games is that players are thrust into the driver’s seat, and while we’re on rails in books or movies, we get to interact with the world in real-time as fast or as slow as we want in this medium, which transports us into worlds—no matter how linear. As the boy and girl, we navigate in third-person, pushing objects, pulling levers, and attaching wheels; REANIMAL does not revolutionize the adventure landscape whatsoever, and some of the gameplay tropes feel tired.

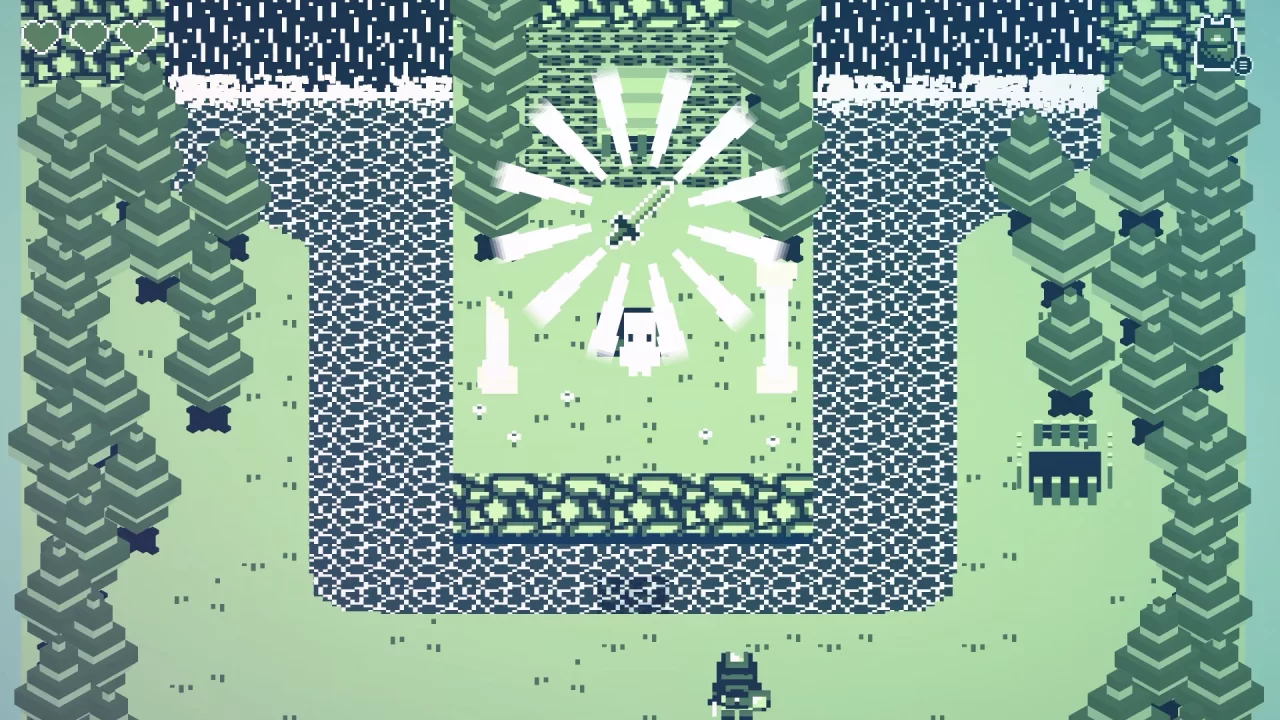

Despite these regurgitated mechanics, the physical world will set players at unease. In tandem with outstanding sound design in a mostly silent world, creepy tunes reminiscent of strings- and percussion-dependent horror movies, and chilling animations, this is a world where pressing forward has more oomph to it than other titles.

I’ve been playing games since the 80s, and you’d think by now I’d be done with holding a direction to run away from a giant enemy with a crumbling ceiling. You’d normally be right, but REANIMAL throws together such cinematic storytelling that these adrenaline-infused breaks from the quiet sprang me to life with urgency. Slithering flesh-folds and amorphous animals kept me from exhaustively exploring environments, and I instead took in the world with blurred periphery. The only real downside to navigating this world lies in fending off foes with a crowbar, which is an awkward and unsatisfying affair when sneaking or using the environment to survive may have served as creepier alternatives.

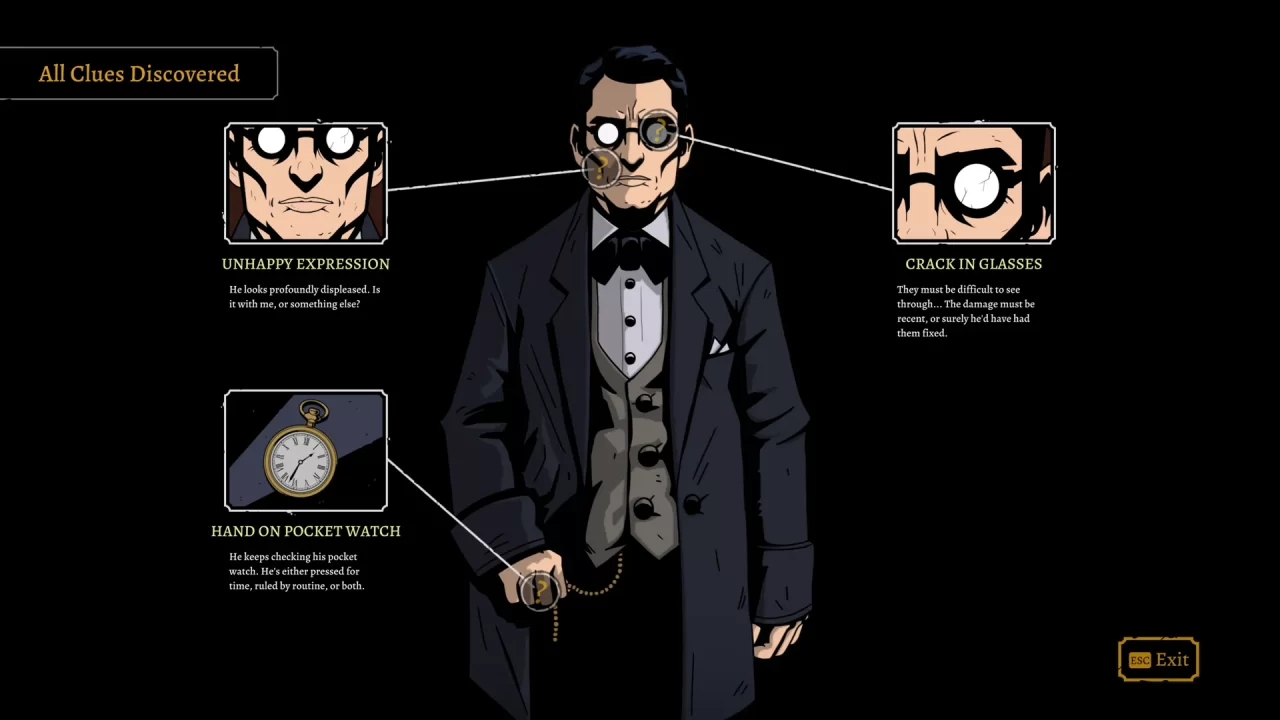

That’s all quibbling, though. I realized by REANIMAL‘s end that I could have more meticulously explored several environments, but in an uncharacteristic few hours of restraint, I pushed on with fleeting moments of exploration. The forced camera does most of the goodies-hiding, too. Pushing on the edges of the screen may reveal secrets hidden by the foreground, which feels like a cheap trick, but still offers that dopamine hit. Still, players may be better served taking the game in rapidly rather than slowing down to engage with the developer-driven hide-and-seek affair; save that for the second playthrough, because the unlocked concept art is some of the best I’ve seen in any game.

In an age when our culture admonishes developers for using AI to create art, REANIMAL displays just how important hand-crafted creation is. Again, after decades of playing video games, I’ve rarely cared about unlocking artwork; in truth, I’ve always found it to be a lazy way of giving something back to the player. Here, I found the artwork stunning and enjoyed seeing what inspired these macabre environments. Every time I found a flailing piece of parchment hanging from a wall, I almost wanted to close out to the main menu just to see what the artists had created. Other hidden collectibles include masks that the children can put on, though these add little to the drab, dark, and grim atmosphere.

Players will undoubtedly judge REANIMAL for its price versus gameplay hours, but the quality of storytelling, visuals, and sound design cannot be argued. The promise of DLC suggests to me that some degree of story clarity will be offered, which I’m not sure how I feel about, but I’m eager for more. Some will call this arthouse schlock, but I remain firm that there’s something here, and even if your last impressions of REANIMAL are slightly less enigmatic days and weeks later, the journey is worthwhile if you don’t fuss over the almighty Dollar.